This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Tether as a Central Bank

Central banks routinely issue money without any reserve backing it. Could Tether do the same and become the first decentralized central bank?

I have expressed before skepticism about Tether (a.k.a USDT) and the fact that a high level of uncertainty still exists on the actual level of reserves backing the token issuance. For all the bad press this uncertainty has created however, a similar situation has occurred regularly in history. Before central banks became the norm, many commercial banks and governments took liberties in issuing money, if only to finance recurring war efforts here and there. In fact couldn’t the same be said of central banks today after the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID economic disaster of early 2020?

At the end of WWII, to avoid a repeat of past monetary crises and install stable foundations for reconstruction and international commerce, governments of developed economies formed and adhered to a new monetary pact, the Bretton-Woods system.

The idea was simple: fix exchange rates between the most important currencies, and back every dollar in circulation with a measurable and controllable inventory of physical asset, and you immediately choke inflationary pressures. Furthermore you prevent political agendas to interfere with monetary policy (in the form of trade wars for example).

The asset chosen for Bretton-Woods was gold, a natural choice at the time. With significant yet slow-growing supply, gold was already a commodity actively traded, and for which trade and storage were already well organized. The final element in the equation was convertibility: anybody in possession of gold could obtain dollars (or any other currency) and vice-versa, at a fixed exchange rate. In reality only governments and central banks were able to convert, a restriction which de factor created two distinct marketplaces for gold: one for central bankers, one for private participants. Convertibility was not an easy feat: it took more than 10 years to fully deploy because of its impact on each participant’s ablitity to control its flow of capital on international markets. Western European economies enforced convertibility in 1958, only when they were strong enough to accomodate free-floating capital flows.

The result was quite remarkable, a period of previously unknown financial stability which in turn paved the way for massive economic growth. For 30 years, the world enjoyed exceptional growth and a quasi-absence of financial crises:

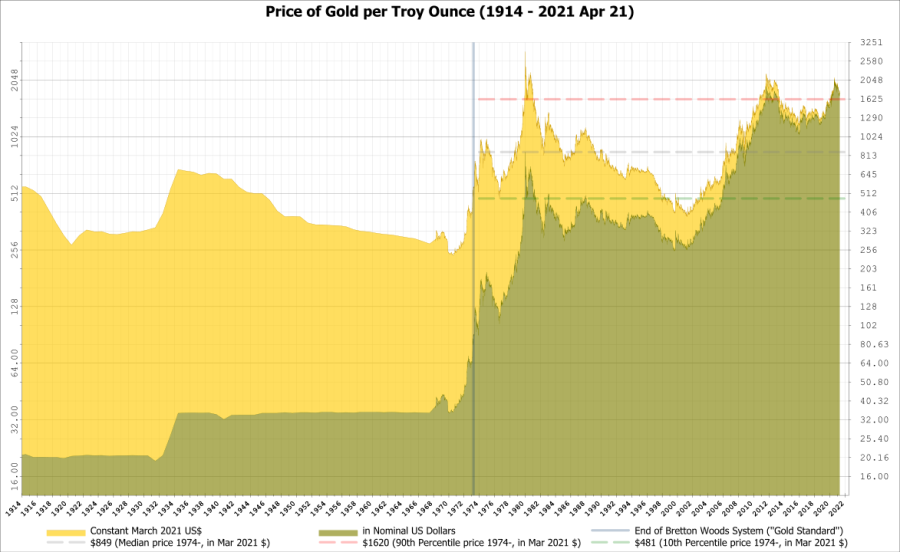

Imbalances were quick to appear though, for reasons intuitively simple: the dollar effectively became the currency of reference and was in high demand. That demand was not fulfilled by a rise in gold supply. The gap between the two created an arbitrage between prices for central bank gold vs. private markets and an unsustainable drain on the US gold reserves:

In 1971 Nixon unilateraly suspended the gold/dollar convertibility and a system of floating exchange rates progressively imposed itself.

Now what does it all have to do with Tether? Well, Tether is effectively used as a settlement currency for bitcoin transactions. Many crypto exchanges do not even list BTC pairs against fiat money. The rise of bitcoin to $60,000 was accompanied by a massive issuance of Tether (and other stable coins incidentally). [NB: there are two reasons for this: one is technical (it is far easier to settle a BTC/USDT transaction than a BTC/USD one), the other reglementary: USDT being totally unregulated, anybody can conduct business using it, whereas conducting business in USD immediately puts you in the perimeter of US regulators].

In the crypto eco-system, Tether is the equivalent of the US dollar in the financial system at the end of WWII: it is the currency that flows throughout the system and enables participants to trade when and where they want. The actual US dollar is the equivalent of gold in Bretton Woods: the undisputed store of value, from which all other currency units draw their value. We have a fixed exchange rate (1 tether = 1 USD) and convertibility at will: look no further, this is a mini-Bretton Woods.

What if Tether announced tomorrow that they don’t want to enforce convertibility anymore, and oh by the way, “we don’t really have a 1-to-1 reserve pool”? The company could keep issuing USDT as it sees fit, feeding the marketplace with enough liquidity to “keep it going”. If indeed all USDT holders consider they have good reasons to hold Tether, because it helps them trade, there’s is really no reason for them to dispose of it. A “Nixon shock” whereby Tether would announce it will not enforce the 1-to-1 parity anymore could be followed by a new rule of floating exchange rate. Would there be a fundamental problem with that? Abolutely not. When Nixon announced the US would not enforce parity anymore it was a unilateral decision, and there’s no doubt there were immediate winners and losers. It was a shock, economically and politically, yet it was not the end of world. The resulting role of Tether would be that of a de-facto all-powerful central bank, controling the reference currency of the crypto eco-system. Quite an enviable position if you ask me.

So why don’t they? As interesting as it sounds, this idea raises a few issues:

- a floating exchange rate means that some people will have lost a lot of money. Contrary to Bretton Woods populated by Secretaries of State and Central Bankers, Tether is a private company and unpegging its USDT from the dollar would amount to nothing less than a fraud if the company was not in a position to repay USDT holders according to the original promise. Now of course, how is that original promise contractualized? What is its legal strength, what could an individual do in front of such a situation? This is difficult to say with certainty, it depends (surprise surprise) on the specifics of Tether situation and on the wording of the (legally binding?) documents behind its token.

- Bretton-Woods was a matter of international public policy, Tether is an unregulated private agent. How trustworthy is it? If it changed the rules once, could it do it again?

- Central banks are extraordinarily transparent. Their charter dictates what they can and cannot do, their operations are usually referred to as “open market” because they are indeed performed in plain sight on open markets. Rules are disclosed, available to all and applicable to all. Their balance sheet is also pubicly available (even though it is after the fact, but it is difficult to operate otherwise). The standard of transparency is so high because of the power they hold over the economy. Would Tether, entrusted with such power, be willing to hold itself to such a standard? Track record so far is not great to say the least.

- In the end, the Federal Reserve is chartered by its national government (the same is true of all central banks). I honestly don’t know if the notion of “public good” is explicit in its charter, but certainly enforcing monetary stability and acting as a lender of last resort both serve public interest. The role of central banks in 2008 and post-COVID is an undeniable testimony to that. Would Tether be willing to commit itself to the promotion of a greater good — as opposed to the promotion of personal interests, whatever those might be? How would we convince ourselves once and for all that it is indeed the case?

- The Federal Reserve draws its legitimacy from the confidence the general pbulic puts in the rule of law and military power of the US (the same goes for the US dollar). Where would Tether draw its legitimacy from? Not quite an easy answer there.

A central bank is the ultimate government-sponsored trusted third party. The crypto eco-system was born in part on the rejection of the “government-sponsored” part, on the idea that it would be possible to build an “algorithmic” trusted third party bypassing the existing financial system and devoid of interference from governments. Can Tether rise to the challenge?

Is Tether a $48 bln scam?

For those who follow the Tether story, there’s been a recent development worth mentioning: the publication of an audit of Tether reserves by a third-party. The statement is available for download on their front page. Tether does have a page with a statement of account (here), but as it is unaudited and uncertified it is not worth much.

There’s been a lot of discussion about whether Tether is a scam of gigantic proportion, but overall those suspicions have had little effect on the rhythm of issuance, reaching today almost $48 bln judging by the latest official figures on coinmarketcap. The immediate and intuitive reaction to this figure is that it’s too big to be anything but real. How could one possibly get away with a scheme of that magnitude?

Unfortunately, it has happened in the past: Madoff (estimated losses $18 bln), Parmalat (when the scandal broke $4 bln were missing), Wirecard ($1.9 bln missing), Enron ($40 bln bankrupcy case following a corporate Ponzi scheme for more than 10 years, during which Enron was celebrated as one of the most innovative US companies). No, size is no guarantee of legitimacy or righteousness.

It is not the intention of this article to state that Tether is or is not a scam, although there are some troubling indicators (see for example the report from New York Attorney General. Tether settled for $18.5 million and was forbidden to conduct business in the State of New York). It belongs to each and everyone of us to build his or her own opinion. I have written before about the typical information an investor should want to acquire about an exchange before opening an account, the purpose of these lines is to apply a similar test to Tether by asking a few basic questions. With 25 years of capital markets experience under the belt, I submit that those questions should be investigated carefully by anybody interested in transacting Tether.

- Who is Tether?

Well, we don’t know. The legal page mentions two legal entities “Tether International Limited” and “Tether Limited”. There is no address, no contact information, no place of incorporation, no regulatory entity. In the privacy policy we learn that Tether is registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) under the number 1939633, with a point of contact in Europe at Chaucer Group Limited, whose registered office is at 10 Lower Thames, London, EC3R 6EN. Still no official address or name, no direct contact information.

The management team shows 3 persons: no email address, no contact info, no linked in profile. On LinkedIn Tether lists 9 employees, among which none of the 3 persons listed on the site appears. In fact CEO, CFO and General Counsel do not appear to have a linkedin profile. Granted, not everybody has a linkedin profile, but for a company entrusted with $48 bln from its clients, all of this is a little…light. Or maybe the site is not fully up to date? No comment.

- Transparency

There are two statements of transparency on Tether’s site: one dated June 1st 2018, the latest one dated Feb 28th 2021. Now a closer look at those documents:

The June 2018 statement is issued by what appears to be a reputable law firm based in Washington. Although a name is given on the letter, it is for reference only, there is no identified signatory, nor is there any mention of an individual personally responsible for the document. This incidentally is often a legal if not ethical obligation from auditors and/or accountants. For example after scandals such as Enron, auditors have to sign their name as an acceptance of the responsibilities they bear in certifying corporate accounts. The list of documents made available to the task force in charge of establishing the letter looks exhaustive and convincing. Strangely enough however, the list doesn’t explicitly mention banking statements. It also doesn’t explicitly mention the names of the two banks concerned. The form of the letter is also unexpected: it is not a public announcement, nor is it meant to be. It is explicitly a “client-attorney communication”, marked as “privileged and confidential”. Also, the document states that “FSS procedures performed are not for the purpose of providing assurance…”. What then is the purpose of this document? It is clearly a step in the right direction but almost raises more questions than it answers.

The Feb 2021 statement is issued by an accounting firm based in the Cayman Islands, “Moore Cayman”. Why not call upon FSS to perform an annual review to establish consistency? What happened between 2018 and 2021? No answer is provided to any of those questions. Like the FSS letter, the Moore document is not signed. Like 2018, none of the financial institutions where the money is deposited are named, nor do we know in which jurisdiction they operate or whether they are even regulated. Like 2018 the statement applies to one point in time, not before, not after. No information is provided as to the beneficial owners of the funds, i.e. which Tether entity has legal responsibility on the corresponding bank accounts. Tether Holdings Limited is mentioned, what is the relationship between this entity and the ones mentioned on Tether’s web site? There is no address, no contact, no email address not even for press inquiries (incidentally the press section doesn’t show anything beyond 2015, which is surprising for a supposedly highly successful company). Moore Cayman may be a reputable firm, but it is fair to say that it absolutely unknown. Recent scandals show that calling upon large internationally recognized law and accounting firms doesn’t guarantee that everything will be ok, but still it goes a long way.

- Risk Management

Tether is entrusted with $48 bln from its clients, the least you would expect is to have some indication on how this money is managed. Furthermore the token part of the equation is based on public blockchains (ethereum and others). Again the least you could expect is to have up-to-date information on the IT governance, in particular who is in charge and what are the resources dedicated to protecting Tether’s clients and infrastructure?

None of this is available on the site. Are those $48 bln invested? If so under what mandate(s), with which level of risk? Who has responsibility for overseeing performance and compliance for this kind of money? Who has responsibility for ensuring the information system is adequately protected and managed? What credentials do the management and IT teams have that give Tether holders some reassurance that their money will not vanish or be hacked? One might argue that if nothing has happened so far, surely the company has shown its ability to manage itself. Well, has something happened? Has money disappeared from bank accounts? Have tokens been hacked? More to the point: would we know if any of this had indeed materialized?

In its “fees” section Tether indicates that it will perform a “verification” to accept new clients. There is no indication of documents, KYC procedure, no address or contact or indication of anything before you submit to this verification (charged $150). Apparently creating or redeeming Tether requires a minimum of $100,000. In all fairness this is probably a consequence of the fact that Tether doesn’t want to offer its services to clients who are not qualified investors (in the sense of US regulation). But in setting such a high threshold, the company loses the opportunity to interact directly with many smaller holders, and hence improve its communication and reputation.

Really, would you give $100,000 to someone you know nothing about, domiciled in one of the least transparent places on Earth, without any idea as to how the money will be safeguarded, invested or used?

…

The question remains as to why Tether management still refuses to provide more transparency. If indeed the company has nothing to hide, putting all questions to rest is astonishingly easy: move the money to a select pool of large well-known banks, and have the statements properly audited by a select pool of large well-known auditing firms. Commit to performing and documenting funds certification for example quarterly and that’s it, you’re done. If Tether wanted to go a step further it could also disclose the investment strategy (or lack thereof) it pursues with the cash under its responsibility. In my mind there is only one reason why the firm doesn’t follow those very simple steps.

Physical delivery and what it means for digital assets

If you ever wondered about the difference between “cash settlement” and “physical delivery” in the world of derivatives, 2020 was a crash course on the matter. Yes, this was the year of negative oil prices, and many will remember those painfully. If Y2K was about fixing a trivial shortcut in date formats, you can bet software developers and risk managers alike were never quite ready for negative oil prices in their systems and scenarios.

What was it about anyway? As always when a situation is more or less “impossible”, there were several converging factors to get to the impossible. The CFTC report names three: an already oversupplied global crude oil market at the beginning of 2020, an unprecedented reduction in demand caused by COVID-19; and concerns about the availability of global crude oil storage.

But what has storage space got to do with this? The missing link is that products exchanged on oil are in fact “physical delivery” futures. That is when a future expires, the buyer physically receives a fixed number of barrels. Furthermore, to standardize the market, deliveries are accepted at only specific locations (see for example the paragraph “delivery procedure” for NYMEX Crude Oil). Any disruption in the flow of oil and storage capacities are easily saturated. In March, this is exactly what happened: a sudden collapse in demand led to a withdrawal from buyers. Markets participants equipped with adequate facilities could collect deliveries and wait it out by keeping their inventory in place. However for participants not properly equipped, holding a future contract meant taking delivery and that was simply not possible because storage at designated facilities was not available. Speculators and traders routinely trading oil without consideration for physical inventory were caught in a “fire sale” spiral in the days leading up to expiry, driving prices in uncharted territory.

You’d be tempted at this point to conclude that physical delivery is a nuisance. Not quite. First of all, it should be pointed out that the commodity market being what it is, physical delivery is the most natural outcome of a transaction between a buyer and a seller. Indeed, “cash settlement” is out of place: it encourages speculation without any consideration for the geographical location of products being traded. And then there’s the other major advantage of physical delivery: it forces convergence between the expiry price of a derivative and the price of its underlying.

Consider for example a future on a stock, cash-settled at expiry. The final reference price of the future is the closing price of the stock (as is the case in the US for example). If you buy the future at $100, and the underlying stock closes at $110 on expiry, you will receive $10 as a final margin call and that’ll be the end of it. If the future is physically delivered, you will receive the stock upon expiry, and the final price being $110 this is what you’ll have to pay. The $10 margin call in your favor means that you effectively bought the stock at $100 - that makes sense because that was the price of the future when you entered the position.

In a world of cash-settled derivatives, the expiry price is set by reference to the underlying, but it doesn’t mean that you can acquire (or dispose of) the underlying at this price. There can be a divergence between those two prices. In a world of physical delivery there cannot - you automatically get ownership of the underlying at the expiry price.

To be specific, let’s take BTC as an example, and in particular the CME BTC Future. The future expires on the CME Bitcoin Reference Rate (BRR), defined as “the aggregation of executed trade flow of major bitcoin spot exchanges during a specific one-hour calculation window“. The future is cash-settled. Upon expiry, CME will calculate a price based on its BRR methodology and will settle the final margin call using that price. The problem is: how do you replicate this price? If you hold a delta-neutral position in bitcoin (long BTC, short future), at expiry you need to unwind the cash BTC leg at the exact same price as the future. That means you need to sell your BTC at the BRR price, no more, no less. This is an ambitious proposition: it implies that i/ you are connected to all relevant exchanges, ii/ you are technology-savvy enough to replicate the BRR real-time exchange allocation, iii/ you can place orders and received executions at the right price at the right time on each exchange. If the BTC future was physically delivered, you would have absolutely nothing to do - you would automatically receive proceeds from delivering BTC as part of the short future.

In traditional markets, this is a well-known problem that occurs for all derivatives that are cash-settled on “exotic” references. For example in France, the CAC 40 index futures settle on an average price over 20 minutes (“Exchange Delivery Settlement Price“). Tradability of the EDSP is an issue for all participants, even those technologically equipped are subject to a convergence risk. This risk is vastly mitigated when settlement prices are set through an auction because the fundamental mechanism of an auction means that everybody is fully served at the same price or the auction doesn’t conclude. Nothing of that sort for BTC or other digital assets: no closing auction, no physical delivery which means that future traders must cope with a simply unpredictable convergence risk.

Now you might wonder…why does it matter? After all, this doesn’t prevent trading, nor does it affect the overall level of risk associated with digital assets. Well, it does affect the ability of the digital industry to introduce secured lending and through it credit-mitigated leverage. I have explained before how the convergence formula of a future contract enables un-coupling between market and credit risk. This however is only possible if convergence is certain. If it is not, secured lending introduces a market risk component that is likely to be unacceptable for yield-seeking lenders. Physical delivery would make secured lending much safer and in turn would pave the way for a truly new chapter: securities financing.

Inflation and digital assets

More than 10 years after the creation of Bitcoin, and as the third “halving” has just taken place, the theme of inflation appears regularly in the digital asset camp. More precisely, it is the idea of an absence of inflation that is presented as disruptive and a guarantee of stability. The idea is interesting, but its application approximate. Let’s take a look at the issue.

- What is inflation?

The dictionary tells us: “Inflation is the loss of the purchasing power of money, which translates into a general and lasting increase in prices”. Put differently, a basket of goods and services that is worth €100 today will be worth more at a later time. Inflation is not good news for a consumer: all other things being equal, purchasing power mechanically decreases.

Inflation is an important psychological factor in consumption. It is because they are afraid of an increase tomorrow that many consumers buy today. Hence the idea that a fall in prices (“deflation”) should be avoided, since it acts as a brake on consumption.

- Inflation is a tax

Inflation is a tax that doesn’t say its name. It is profoundly egalitarian since all economic agents are affected equally, and profoundly unfair since those who suffer most are the low income earners whose erosion of purchasing power is often not compensated by an increase in income. But if we are indeed in the presence of a tax, is the State the beneficiary? Yes and no, we will come back to that.

- Inflation has two major sources

Broadly speaking, inflation occurs for two reasons:

- First, as a consequence of demand-led economic growth. The principle is simple and sound: demand for a good gradually increases its price. At the scale of an economy, in periods of strong growth all prices are pulled up. Wages are then likely to be adjusted upwards as well, either because corporate profitability allows it, or because the labor market tightens when unemployment falls. This is the inflation that everyone dreams of.

- The other form of inflation is an increase in the money supply. Literally, if tomorrow the stock of money increases by 10%, the price of goods and services in the economy will mechanically increase by 10%. This inflation is much more insidious, its effects are not always beneficial, and it can exist in the absence of economic growth. In this case, it will be harder for wages to keep up with prices, since businesses do not see a solid demand for their products.

Understanding inflation therefore also means looking at the money supply, i.e. the mass of money in circulation. And what is the pillar of money creation? Credit. It is therefore impossible to talk about inflation without talking about credit.

- Inflation and credit

An accommodative monetary policy, i.e. a policy in which credit creation is facilitated (e.g. by keeping interest rates low) is inflationary. Here lies the first of a consumer’s great contradictions: asking for an abundance of low-cost credit does not go hand in hand with low inflation.

“The link between inflation and credit is so strong that central banks are assigned the responsibility for maintaining price stability.”

The European Central Bank, like the US Federal Reserve, often comments on the subject: their consensus places beneficial inflation around 2%. Central banks must therefore steer monetary policy between two constraints: authorizing the creation of money (in the form of credit) to promote economic development, without falling into the opposite excess which would encourage inflation and erode purchasing power.

- Inflation and wealth transfer

If inflation is a tax, who collects it? Governments benefit from moderate inflation (in particular for the dilution of their debt, see below), but it is not a tax in the traditional sense, i.e. a mass of money collected by public authorities. In fact, inflation organizes a transfer of wealth between economic agents.

To my left are the bearers of money (notes, coins, current accounts etc), that is to say everyone. On my right the mass of borrowers — be they public or private, whatever type of debt they have contracted. Inflation is a transfer from the former to the latter. The wealth of the first group, expressed in monetary units, is devalued by inflation every year. For exactly similar reasons, the debt of the second group is also devalued through inflation every year. But this devaluation is a blessing: if I pay back €1,000 every month for 15 years, the purchasing power of that €1,000 falls over time. Today an effort of €1,000 per month is what it is, but after 15 years of inflation it is certain to be much less constraining.

In essence, this is the consumer’s other damnation: high inflation reduces purchasing power, but it also greatly increases his debt capacity, especially for the debt that dominates in terms of amount and duration — mortgages.

What is true for a household is also true for a state or a company: reasonable inflation makes it possible to absorb debt more quickly. Central banks are therefore in a difficult position: to let inflation run its course and allow governments to “dilute” their debt with the comfort that this represents for fiscal policy, or to actively fight inflation to safeguard purchasing power but with the rigor that this implies on interest rates.

- Inflation and interest rates

Is there a simple way to regulate the transfer of wealth that inflation organizes in an economy? Absolutely: through interest rates. To return to the example above, suppose that the €1,000 monthly repayment corresponds to an interest rate of 5% per annum on a loan of €240,000. Now suppose that my repayments are indexed to inflation, i.e. adjusted for inflation every year. If, for example, inflation materializes at 2.5%, I find myself paying back 7.5% per year, i.e. €1,500 per month instead of €1,000. This indexation protects the lender since at any time he or she captures the depreciation of purchasing power as overlay on the initial interest.

A sound monetary policy consists in controlling the general level of interest rates to regulate credit, the money supply and ultimately inflation. In periods of high inflation a central bank will raise rates, which has the immediate effect of slowing down credit and increasing the remuneration of lenders. However, raising interest rates and limiting credit also has negative effects on the economy, since businesses (and individuals) have more difficulty financing their investments.

These observations explain why many loans are indexed to variable rates. However, this is not the case for government bonds, which are mostly issued at fixed rates. Put another way, a government (fixed-rate) loan is much less protected against inflation than a variable-rate loan, especially over long periods of time. Real estate loans in France for example are massively fixed-rate, which in fact protects the borrower at the expense of the bank. In the US or the UK, mortgages are “adjustable-rate mortgages” (ARM), i.e. loans with adjustable rates, allowing financial institutions to protect themselves against inflation — at least to some extent.

- Bretton Woods

Is a world without monetary inflation possible? In fact it has existed recently, it was the world of the Bretton Woods accords (1944–1976). At the end of World War II, the great powers wanted a monetary system that would promote stability, in particular to avoid episodes of hyperinflation like Germany between the two wars. The Bretton Woods framework stipulated that currency exchange rates were fixed in relation to the US dollar, while the value of the dollar was fixed in relation to gold ($35 per ounce). This system of fixed exchange rates against gold prevented uncontrolled monetary creation on the dollar and consequently on other currencies.

“In Bretton Woods, a close control of monetary creation implied a strong constraint on credit creation. And a strong constraint on credit creation resulted in…a period of unprecedented stability.”

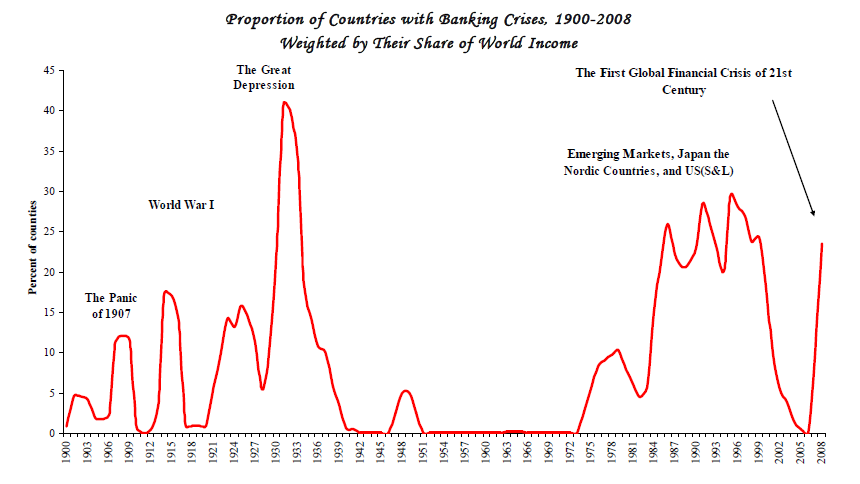

The following graph shows the percentage of countries in a state of financial crisis between 1900 and 2008:

Source: “Banking Crises: An Equal Opportunity Menace”, Carmen M. Reihnart, Kenneth S. Rogoff, NBER Working Paper 14587.

It is clear that the application of Bretton Woods corresponds to a period of calm that did not exist either before or after — even when there was lasting peace. From this the conclusion that uncontrolled money creation linked to credit creates at least as many problems as it solves is only a step away. After Bretton Woods, most financial crises had their source in the encounter of massive indebtedness and capricious economic activity.

- Inflation and digital assets

Most digital assets have the characteristic of having “hard-coded” inflation in their protocol. This is the case for bitcoin, ethereum and many others. This inflation is of a monetary type, i.e. it does not correspond to an increase in prices, but to the creation of money. As no other inflation is possible since there is no central bank to regulate the quantity of money, it follows that there is no creation of credit on these protocols. To borrow, one must therefore find someone who lends the assets he owns. Similarly, there is no room for a commercial bank in these systems, since their main function in real life is not account keeping but credit creation.

The claim that digital assets offer protection against inflation is absolutely correct. But it comes at the price of a lack of credit. In an economy based on a digital currency, consumer-citizens could find that there is no inflation linked to money creation (beyond the one coded in the protocol). They might find that there is no bank to charge account fees, but they might just as well realize that getting credit to buy their home is a miracle. In a world where money supply is limited, getting credit is akin to convincing someone to lend you their savings. All borrowers are in direct competition with each other for a limited resource. Moreover, the absence of monetary inflation does not imply the total absence of inflation, only the second inflationary mechanism disappears. If a digital currency were available to buy oranges, the producer could very well decide to increase his prices on his own in the face of strong demand.

- Conclusion

While it is quite true that the absence of inflation offers security for holders in relation to national currencies, this assertion must be supplemented by the observation that an economy based on a digital currency would be nothing like the one we have today. In the absence of credit, governments (and businesses and individuals) would see their indebtedness capacity seriously eroded. What would be the best use of a unit of currency available for borrowing? A car, a factory, the public deficit? And what would be its price? What interest rate would have to be paid to the bearer of this unit for him to accept the credit risk of a given borrower?

Economies of this type have existed throughout human history, including during periods of industrialization. There is therefore no theoretical impossibility for their reappearance. But the world today is so overburdened with debt that it is difficult to imagine such a return.