This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Tether Reserves: at it again

So much for “Unrivaled transparency”

As a capital market professional, I have expressed before (here) how skeptical I was about Tether and its so-called “transparency”. For all intent and purposes, Tether looks more and more like a traditional bank with “fractional reserves”, a very ancient and old-fashioned way of operating a banking business, in which the bank doesn’t hold reserves for all the money it has issued (ignoring for a second the underlying fraud that this situation constitutes in the case of Tether). For a newcomer supporting the total disruption of finance as we know it, the resurgence of a centuries-old business model is somewhat ironic. What’s even more ironic is that the old way in banking is fundamentally built on trust. Remove trust and the entire system collapses through bank runs. The blockchain technology is supposed to take us away from traditional trusted third parties. And yet here we are, asking questions about Tether reserves, which fundamentally Tether cannot answer without the certification of…a trusted third-party.

As requested in the settlement with the Attorney General of the State of New York, Tether just disclosed the breakdown of its reserves as of 3/31/2021, here. The reader will appreciate the conciseness of this report,1 single page, 2 charts — no more, no less. We are not lost in details. Considering the annual report of any decent bank today is 400-page long and quite incomprehensible, the fact that Tether operates outside any sort of regulation simplifies the task. It has been said before: the list of gaps is staggering — no risk analysis, no indication of yield, no performance measurement, no mention of who is in charge, etc, etc. And still, no audit certification, no contact information, no signatory. Good luck to all of us with questions.

The story has been picked up by mainstream media, for example, the Financial Times a few days ago (“Tether says its reserves are backed by cash to the tune of . . . 2.9%”). That anybody would buy Tether in these circumstances is extraordinary. And this is exactly what one of our clients asked us last week: “if Tether is such a big concern, why does it still trade at $1? If markets were even somewhat efficient, its value would have adjusted with the perceived risk no?”. Indeed, this is a legitimate question. After reflecting on this for a few days, here are some answers, the only ones I can provide in fact:

- The market knows something that I don’t. Fair enough. Then again, a lot of people appear not to know anything, to the point where you start wondering whether there is something to be known.

- People don’t care. This is another way of saying that the market is inefficient to the point that Tether holders neglect the risk entirely. This is not so difficult to believe: a large fraction of crypto-investors are non-professional, and as such do not approach risk analysis the way professionals do. The opportunity to make 100% in a few weeks could sweep any restraint away. As for those who do understand what risk is about, they may choose to use Tether as a means to an end, namely to access other digital assets. In doing so they would choose to hold Tether only for short periods thereby mitigating their risk significantly.

- People choose not to care. That’s a subtler one. What would happen if tomorrow Tether announced that it holds only 75% of its total issuance? 60%? 40%? The shockwave through the crypto ecosystem would be disastrous. There would probably be numerous public inquiries and lawsuits, who knows if the digital asset economy would even survive such a tsunami. Better not ask a question you don’t want an answer to.

- Finally, another option to consider: some market participants may be willing to buy Tether (also known as USDT) aggressively any chance they get when it “breaks the buck” below $1. Some of those buyers might be interested in quick arbitrage profits, but some may just be trying to bring it back to $1 because it is in their best interest. Now, who would have a vested interest in keeping the USDT at $1? Tether itself. If more USDT have been issued than the reserves allow, the excess has almost certainly been invested in other digital assets, bitcoin first and foremost. If Tether were to trade below $1, it would be fairly easy to sell those bitcoin back against USDT to maintain the level of USDT. The more Tether has been issued without reserves, the more ammunition it gives manipulators to intervene and bring the USDT back to $1.

Where is the truth? What is going on with Tether, and more importantly do we really have a way of knowing? Probably no without the help of a proper due diligence process, and only regulators have the power to make this happen.

Tether as a Central Bank

Central banks routinely issue money without any reserve backing it. Could Tether do the same and become the first decentralized central bank?

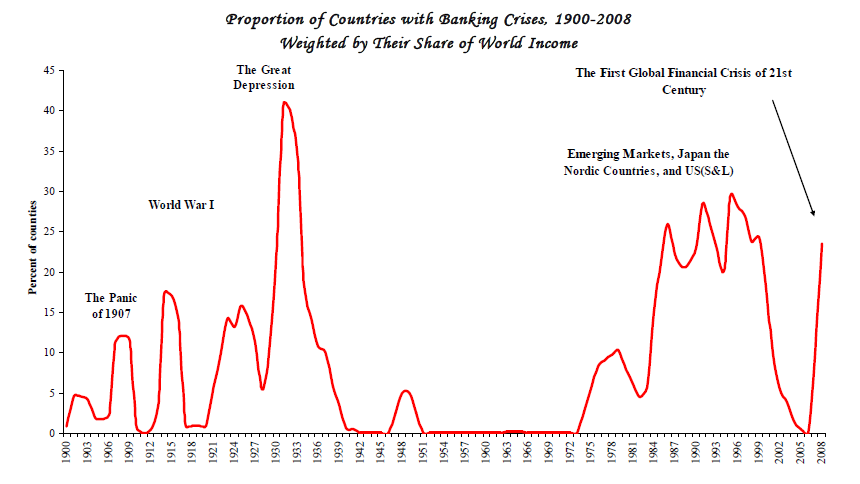

I have expressed before skepticism about Tether (a.k.a USDT) and the fact that a high level of uncertainty still exists on the actual level of reserves backing the token issuance. For all the bad press this uncertainty has created however, a similar situation has occurred regularly in history. Before central banks became the norm, many commercial banks and governments took liberties in issuing money, if only to finance recurring war efforts here and there. In fact couldn’t the same be said of central banks today after the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID economic disaster of early 2020?

At the end of WWII, to avoid a repeat of past monetary crises and install stable foundations for reconstruction and international commerce, governments of developed economies formed and adhered to a new monetary pact, the Bretton-Woods system.

The idea was simple: fix exchange rates between the most important currencies, and back every dollar in circulation with a measurable and controllable inventory of physical asset, and you immediately choke inflationary pressures. Furthermore you prevent political agendas to interfere with monetary policy (in the form of trade wars for example).

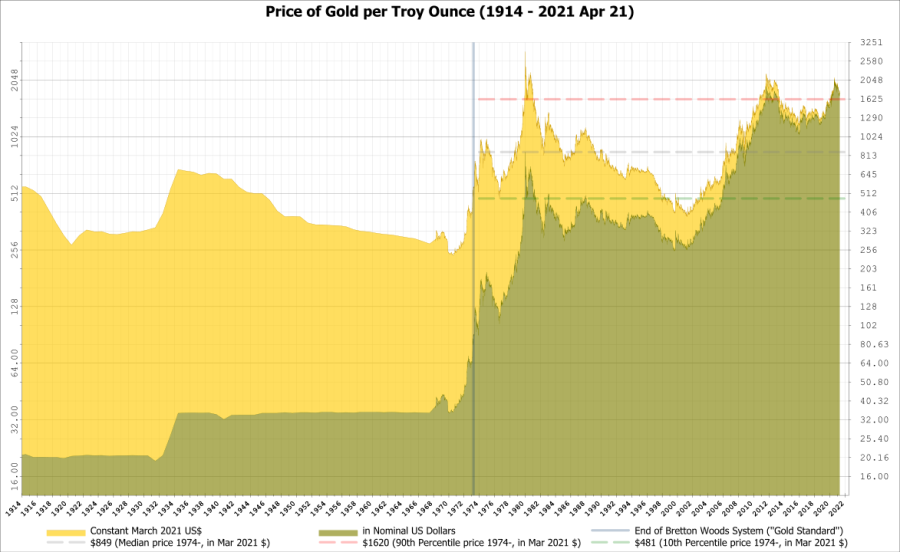

The asset chosen for Bretton-Woods was gold, a natural choice at the time. With significant yet slow-growing supply, gold was already a commodity actively traded, and for which trade and storage were already well organized. The final element in the equation was convertibility: anybody in possession of gold could obtain dollars (or any other currency) and vice-versa, at a fixed exchange rate. In reality only governments and central banks were able to convert, a restriction which de factor created two distinct marketplaces for gold: one for central bankers, one for private participants. Convertibility was not an easy feat: it took more than 10 years to fully deploy because of its impact on each participant’s ablitity to control its flow of capital on international markets. Western European economies enforced convertibility in 1958, only when they were strong enough to accomodate free-floating capital flows.

The result was quite remarkable, a period of previously unknown financial stability which in turn paved the way for massive economic growth. For 30 years, the world enjoyed exceptional growth and a quasi-absence of financial crises:

Imbalances were quick to appear though, for reasons intuitively simple: the dollar effectively became the currency of reference and was in high demand. That demand was not fulfilled by a rise in gold supply. The gap between the two created an arbitrage between prices for central bank gold vs. private markets and an unsustainable drain on the US gold reserves:

In 1971 Nixon unilateraly suspended the gold/dollar convertibility and a system of floating exchange rates progressively imposed itself.

Now what does it all have to do with Tether? Well, Tether is effectively used as a settlement currency for bitcoin transactions. Many crypto exchanges do not even list BTC pairs against fiat money. The rise of bitcoin to $60,000 was accompanied by a massive issuance of Tether (and other stable coins incidentally). [NB: there are two reasons for this: one is technical (it is far easier to settle a BTC/USDT transaction than a BTC/USD one), the other reglementary: USDT being totally unregulated, anybody can conduct business using it, whereas conducting business in USD immediately puts you in the perimeter of US regulators].

In the crypto eco-system, Tether is the equivalent of the US dollar in the financial system at the end of WWII: it is the currency that flows throughout the system and enables participants to trade when and where they want. The actual US dollar is the equivalent of gold in Bretton Woods: the undisputed store of value, from which all other currency units draw their value. We have a fixed exchange rate (1 tether = 1 USD) and convertibility at will: look no further, this is a mini-Bretton Woods.

What if Tether announced tomorrow that they don’t want to enforce convertibility anymore, and oh by the way, “we don’t really have a 1-to-1 reserve pool”? The company could keep issuing USDT as it sees fit, feeding the marketplace with enough liquidity to “keep it going”. If indeed all USDT holders consider they have good reasons to hold Tether, because it helps them trade, there’s is really no reason for them to dispose of it. A “Nixon shock” whereby Tether would announce it will not enforce the 1-to-1 parity anymore could be followed by a new rule of floating exchange rate. Would there be a fundamental problem with that? Abolutely not. When Nixon announced the US would not enforce parity anymore it was a unilateral decision, and there’s no doubt there were immediate winners and losers. It was a shock, economically and politically, yet it was not the end of world. The resulting role of Tether would be that of a de-facto all-powerful central bank, controling the reference currency of the crypto eco-system. Quite an enviable position if you ask me.

So why don’t they? As interesting as it sounds, this idea raises a few issues:

- a floating exchange rate means that some people will have lost a lot of money. Contrary to Bretton Woods populated by Secretaries of State and Central Bankers, Tether is a private company and unpegging its USDT from the dollar would amount to nothing less than a fraud if the company was not in a position to repay USDT holders according to the original promise. Now of course, how is that original promise contractualized? What is its legal strength, what could an individual do in front of such a situation? This is difficult to say with certainty, it depends (surprise surprise) on the specifics of Tether situation and on the wording of the (legally binding?) documents behind its token.

- Bretton-Woods was a matter of international public policy, Tether is an unregulated private agent. How trustworthy is it? If it changed the rules once, could it do it again?

- Central banks are extraordinarily transparent. Their charter dictates what they can and cannot do, their operations are usually referred to as “open market” because they are indeed performed in plain sight on open markets. Rules are disclosed, available to all and applicable to all. Their balance sheet is also pubicly available (even though it is after the fact, but it is difficult to operate otherwise). The standard of transparency is so high because of the power they hold over the economy. Would Tether, entrusted with such power, be willing to hold itself to such a standard? Track record so far is not great to say the least.

- In the end, the Federal Reserve is chartered by its national government (the same is true of all central banks). I honestly don’t know if the notion of “public good” is explicit in its charter, but certainly enforcing monetary stability and acting as a lender of last resort both serve public interest. The role of central banks in 2008 and post-COVID is an undeniable testimony to that. Would Tether be willing to commit itself to the promotion of a greater good — as opposed to the promotion of personal interests, whatever those might be? How would we convince ourselves once and for all that it is indeed the case?

- The Federal Reserve draws its legitimacy from the confidence the general pbulic puts in the rule of law and military power of the US (the same goes for the US dollar). Where would Tether draw its legitimacy from? Not quite an easy answer there.

A central bank is the ultimate government-sponsored trusted third party. The crypto eco-system was born in part on the rejection of the “government-sponsored” part, on the idea that it would be possible to build an “algorithmic” trusted third party bypassing the existing financial system and devoid of interference from governments. Can Tether rise to the challenge?

Is Tether a $48 bln scam?

For those who follow the Tether story, there’s been a recent development worth mentioning: the publication of an audit of Tether reserves by a third-party. The statement is available for download on their front page. Tether does have a page with a statement of account (here), but as it is unaudited and uncertified it is not worth much.

There’s been a lot of discussion about whether Tether is a scam of gigantic proportion, but overall those suspicions have had little effect on the rhythm of issuance, reaching today almost $48 bln judging by the latest official figures on coinmarketcap. The immediate and intuitive reaction to this figure is that it’s too big to be anything but real. How could one possibly get away with a scheme of that magnitude?

Unfortunately, it has happened in the past: Madoff (estimated losses $18 bln), Parmalat (when the scandal broke $4 bln were missing), Wirecard ($1.9 bln missing), Enron ($40 bln bankrupcy case following a corporate Ponzi scheme for more than 10 years, during which Enron was celebrated as one of the most innovative US companies). No, size is no guarantee of legitimacy or righteousness.

It is not the intention of this article to state that Tether is or is not a scam, although there are some troubling indicators (see for example the report from New York Attorney General. Tether settled for $18.5 million and was forbidden to conduct business in the State of New York). It belongs to each and everyone of us to build his or her own opinion. I have written before about the typical information an investor should want to acquire about an exchange before opening an account, the purpose of these lines is to apply a similar test to Tether by asking a few basic questions. With 25 years of capital markets experience under the belt, I submit that those questions should be investigated carefully by anybody interested in transacting Tether.

- Who is Tether?

Well, we don’t know. The legal page mentions two legal entities “Tether International Limited” and “Tether Limited”. There is no address, no contact information, no place of incorporation, no regulatory entity. In the privacy policy we learn that Tether is registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) under the number 1939633, with a point of contact in Europe at Chaucer Group Limited, whose registered office is at 10 Lower Thames, London, EC3R 6EN. Still no official address or name, no direct contact information.

The management team shows 3 persons: no email address, no contact info, no linked in profile. On LinkedIn Tether lists 9 employees, among which none of the 3 persons listed on the site appears. In fact CEO, CFO and General Counsel do not appear to have a linkedin profile. Granted, not everybody has a linkedin profile, but for a company entrusted with $48 bln from its clients, all of this is a little…light. Or maybe the site is not fully up to date? No comment.

- Transparency

There are two statements of transparency on Tether’s site: one dated June 1st 2018, the latest one dated Feb 28th 2021. Now a closer look at those documents:

The June 2018 statement is issued by what appears to be a reputable law firm based in Washington. Although a name is given on the letter, it is for reference only, there is no identified signatory, nor is there any mention of an individual personally responsible for the document. This incidentally is often a legal if not ethical obligation from auditors and/or accountants. For example after scandals such as Enron, auditors have to sign their name as an acceptance of the responsibilities they bear in certifying corporate accounts. The list of documents made available to the task force in charge of establishing the letter looks exhaustive and convincing. Strangely enough however, the list doesn’t explicitly mention banking statements. It also doesn’t explicitly mention the names of the two banks concerned. The form of the letter is also unexpected: it is not a public announcement, nor is it meant to be. It is explicitly a “client-attorney communication”, marked as “privileged and confidential”. Also, the document states that “FSS procedures performed are not for the purpose of providing assurance…”. What then is the purpose of this document? It is clearly a step in the right direction but almost raises more questions than it answers.

The Feb 2021 statement is issued by an accounting firm based in the Cayman Islands, “Moore Cayman”. Why not call upon FSS to perform an annual review to establish consistency? What happened between 2018 and 2021? No answer is provided to any of those questions. Like the FSS letter, the Moore document is not signed. Like 2018, none of the financial institutions where the money is deposited are named, nor do we know in which jurisdiction they operate or whether they are even regulated. Like 2018 the statement applies to one point in time, not before, not after. No information is provided as to the beneficial owners of the funds, i.e. which Tether entity has legal responsibility on the corresponding bank accounts. Tether Holdings Limited is mentioned, what is the relationship between this entity and the ones mentioned on Tether’s web site? There is no address, no contact, no email address not even for press inquiries (incidentally the press section doesn’t show anything beyond 2015, which is surprising for a supposedly highly successful company). Moore Cayman may be a reputable firm, but it is fair to say that it absolutely unknown. Recent scandals show that calling upon large internationally recognized law and accounting firms doesn’t guarantee that everything will be ok, but still it goes a long way.

- Risk Management

Tether is entrusted with $48 bln from its clients, the least you would expect is to have some indication on how this money is managed. Furthermore the token part of the equation is based on public blockchains (ethereum and others). Again the least you could expect is to have up-to-date information on the IT governance, in particular who is in charge and what are the resources dedicated to protecting Tether’s clients and infrastructure?

None of this is available on the site. Are those $48 bln invested? If so under what mandate(s), with which level of risk? Who has responsibility for overseeing performance and compliance for this kind of money? Who has responsibility for ensuring the information system is adequately protected and managed? What credentials do the management and IT teams have that give Tether holders some reassurance that their money will not vanish or be hacked? One might argue that if nothing has happened so far, surely the company has shown its ability to manage itself. Well, has something happened? Has money disappeared from bank accounts? Have tokens been hacked? More to the point: would we know if any of this had indeed materialized?

In its “fees” section Tether indicates that it will perform a “verification” to accept new clients. There is no indication of documents, KYC procedure, no address or contact or indication of anything before you submit to this verification (charged $150). Apparently creating or redeeming Tether requires a minimum of $100,000. In all fairness this is probably a consequence of the fact that Tether doesn’t want to offer its services to clients who are not qualified investors (in the sense of US regulation). But in setting such a high threshold, the company loses the opportunity to interact directly with many smaller holders, and hence improve its communication and reputation.

Really, would you give $100,000 to someone you know nothing about, domiciled in one of the least transparent places on Earth, without any idea as to how the money will be safeguarded, invested or used?

…

The question remains as to why Tether management still refuses to provide more transparency. If indeed the company has nothing to hide, putting all questions to rest is astonishingly easy: move the money to a select pool of large well-known banks, and have the statements properly audited by a select pool of large well-known auditing firms. Commit to performing and documenting funds certification for example quarterly and that’s it, you’re done. If Tether wanted to go a step further it could also disclose the investment strategy (or lack thereof) it pursues with the cash under its responsibility. In my mind there is only one reason why the firm doesn’t follow those very simple steps.

What is prime brokerage and how does it apply to digital assets?

There is a lot of talk in the crypto economy about prime brokerage: many participants frame themselves as “prime brokers” (PB), with the usual superlatives. What exactly are we talking about? A broker is an intermediary between a buyer and a seller: for a multitude of reasons despite the costs involved, it often makes sense to “intermediate” a transaction. This is the case for corporate mergers & acquisitions, real estate, a large fraction of products in capital markets, auctioning art, etc. But what are the prime services offered by a broker beyond execution (i.e. the matching of buyer and seller)?

In traditional finance, prime services include the following:enhanced execution services: those may be for example access to a low latency environment, co-location at an exchange data center, custom-made trading algorithms that may not be widely available to the broker’s client base, etc. In some instances, a PB might even allow a client to trade under the broker’s membership for better performance and/or lower costs.

- custody of assets: this is fairly customary, most broker-dealers offer custody services as part of an integrated solution (but sometimes using a distinct legal entity). Client accounts may be co-mingled (all in the same place) or segregated (in individual accounts). Co-mingling assets is practical and cost-effective for the PB (for example for settlement and delivery) but presents an element of risk for the client (in 2008 some of Lehman clients discovered that their assets were not segregated. As a result their claims was much harder to enforce in the liquidation proceedings). Segregation dramatically facilitates property claims in case of default but is regulatory and operationally more costly.

- operations: commonly referred to as “back-office”. A PB will make its back office available to address the settlement needs of its clients, from basic cash and derivative settlement to OTC reconciliation, margining, and corporate actions. Back-office operations are a very tedious universe. While many operations are “straight-through”, a lot of situations arise that need manual intervention. A PB will essentially allow an investment fund to outsource all its “ops” department, thereby significantly reducing its fixed-cost base.

- portfolio valuation: third-party valuation is a basic requirement in the world of asset management. PBs fulfill that need for their risk monitoring requirements but also the benefit of final investors.

- funding (i.e. secured lending): that’s a big one. A lot of asset managers, especially speculative hedge funds, employ leverage. The principle is quite simple: the fund borrows money to buy assets, those assets are then deposited as a guarantee against the loan. The interest rate paid for this loan reflects the type of assets, their liquidity, and naturally includes a commercial margin that is client-specific. Funding is a very important part of a PB revenue mix because of its diversifying nature. Execution is a transactional business: no trade, no gain. Funding is an accrual stream: the simple carry of a position brings revenues day after day until the position is unwound.

- short-covering: for a portfolio manager trying to gain a short exposure in the market, the pre-requisite is finding the right instrument to build this exposure. Today “naked short-selling” -i.e. the sale of an instrument without having secured the possibility to deliver- is mostly forbidden. For example, a stock cannot be sold short if it hasn’t been “located” to borrow prior to the sale. Being able to locate inventory at a fair price is a critical competitive advantage for PB. A client can naturally request a locate from intermediaries other than its regular PB, but the cost is most certainly higher and practicalities can be tricky (on-time settlement for example).

- regulatory reporting: not much to detail here. The trend is towards more of this, outsourcing this function is a no-brainer for many clients.

- risk management and reporting: risk management is naturally a function of each client’s strategy and mandate. There are three reasons however why PBs have stringent risk management practices in place: i/ they need to make sure that they can survive a client’s default, and if possible even anticipate it so that market-wide damage is minimal; ii/ in the presence of leverage, there is a credit element to risk management: a sudden market drop could result in dramatic losses because of leverage; iii/ regulators impose it, implicitly as a way to overlay a third-party risk monitoring layer. Many hedge funds are unregulated: final investors and regulators can find reassurance in the fact that well-established PBs keep a close eye on their risk engagements.

- fundraising: because of their extensive connections with final investors, institutional and otherwise, PBs routinely help their clients find new money.

- synthetic format: prime brokerage was historically a cash business i.e. clients would physically buy and detain the assets. With the development of derivatives, a new format emerged: “synthetic prime brokerage”. In a synthetic arrangement, the client doesn’t hold the assets. Those are on the PB’s balance sheet and the client holds a derivative that mirrors the portfolio’s exposure — it usually takes the form of a total-return swap (TRS). The synthetic format offers many advantages from a client standpoint, in particular its simplicity. However, this simplicity comes with an additional layer of legal complexity due to the fact that a derivative product is involved.

Now, what about the crypto space? Are prime brokers there close to providing prime services to their clients? Not by a long stretch. One could argue that there are in fact only very few true prime brokers for digital assets. Some functions are highly relevant (e.g. execution), some don’t even have an equivalent, for example regulatory reporting which is non-existent (today).

The most fundamental interrogation is this: do digital assets possess intrinsic characteristics that would prevent nascent digital capital markets to grow and converge towards their cousins on traditional instruments? Well, at SUN ZU Lab we don’t think so, quite the contrary. In principle, we think digital assets have tremendous potential to equal and even surpass some traditional assets. With two caveats:

- the industry needs to aggressively embrace self-discipline if not self-regulation: conflicts of interest are widespread, opacity is the rule, not the exception. Embracing self-regulation will promote cooperation and contribute to forging a common vision. In turn this vision will help consolidate relevant technologies, and forge a path to much needed standardization.

- market participants need to make peace with traditional regulation. Not all of it is relevant or applicable, but regulators worldwide care about only one thing: protecting investors, especially non-professional ones. The digital asset industry need to recognize this fact and make it its mission to help.

Everything you’ve always wanted to ask your crypto exchange

Whoever has been working in an investment bank knows that regulation is a big deal, even more so after 2008. By contrast, the world of digital assets is largely unregulated.

What is regulation anyway, why does it even exist? It could be argued that regulators worldwide have a single objective: to protect investors, small and big alike. What do investors need protection from? For the sake of simplicity let’s abstract this to the simplest notion : “information asymmetry”. Financial markets deal with information, assimilating information into price to obtain the “fair price” of a product or service. Information asymmetry means that one of the parties to a transaction knows more (or understands better) than the other, and as a result the price formed during that transaction is biased, resulting in a transfer of wealth from the less knowledgeable to the more knowledgeable.

“For those tempted to believe morons should lose their shirt, let me offer the following proposition: you always are somebody else’s moron.“

The information or knowledge we are talking about is somewhat specific. Two investors may differ in their belief that a particular situation will occur (for example XYZ stock price will go up), as a result will take different risks. Fine. But if a trader sells a complex product to a retail investor, it is most certain that the former has much better understanding of the associated risks, and may not be entirely forthcoming about those. This is the kind of asymmetry regulation is meant to address.

Coming back to the above transfer of wealth, one might argue the “fairness” of that transfer – which may or may not be part of the regulator’s mandate. What is beyond doubt however is that the global allocation of resources in the economy will be biased as well, resulting in inefficient and sub-optimal development (or unacceptable risks for unsophisticated investors). It comes as no surprise then that regulators’ first weapon is transparency, expressed as a disclosure obligation. After all the best way to make sure that everybody is on the same page is to force the more knowledgeable party to share information. That is exactly what has happened in the past 10 years in the realm of traditional markets. Disclosure goes a long way: from traders having to disclose their profit margin to clients, to financial institutions having to disclose employee compensation.

* * *

If we turn to the mostly unregulated digital eco-system, we should certainly ask the same question: if regulation served a purpose in traditional markets, specifically around the theme of transparency, shouldn’t we apply the same standards for the benefit of the largest number of investors? Presumably those would feel better protected and would increase their activity. In addition this sense of security would probably convince “by-standers” to join in.

Many argue regulation stifles innovation. But would transparency stifle innovation?

Well I confess that in my view transparency, whether volontary or imposed, is a fundamental component of “fair and orderly” markets, so I certainly hope we’ll see more of it. And in fact we might as well start looking for it right away.

If you were a trader in an investment bank, trying to become member of a new exchange, you would face a barrage of questions from all fronts: management, risk and compliance, even tax and accounting. Have you asked your crypto exchange the same questions? If those are legitimate for a regular exchange, why wouldn’t they be for any kind of marketplace? So what kind of information would a trader want to acquire i.e. what kind of question would you be wise to ask your crypto exchange (or any other intermediary for that matter)?

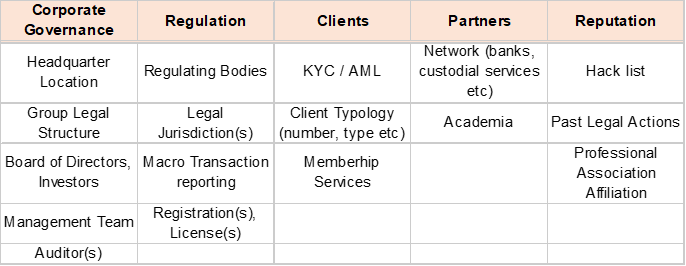

Let’s distinguish trading and non-trading. The table below gives a non-exhaustive list of non-trading relevant information:

It all has to do with common sense curiosity: who am I dealing with? what economic interests am I facing, what kind of legal protection am I entitled to (if any)? Does the exchange have a history of reputational issues such as hacking? What is the qualification of the management team and what governance are they facing?

It is not the point here to detail all the items, but to give a sense of the extent of information regulators would want you to have under the “disclosure” obligation before you open a new business relationship. By the way exchanges also want to know who they’re dealing with, that’s the point of KYC investigation. It’s only fair you/we return the questions.

One item might be surprising: “academia”. Well, believe it or not it is far-reaching. Many scandals in financial markets (and elsewhere) have emerged from the work of independent researchers. Exchanges worldwide routinely provide confidential trading data to the academic world to facilitate applied financial research. Such data is incidentally also made available to national regulators.

Is that mass of information readily available from traditional exchanges? Absolutely, it may not be 100% present on their web site (here or here for example), but it is available to clients and qualified prospects. Is it readily available for crypto exchanges? No, not by a long stretch. Should it be? Well, in the absence of legal obligation, it is anybody’s call. One could argue however that disclosure goes a long way in establishing trust.

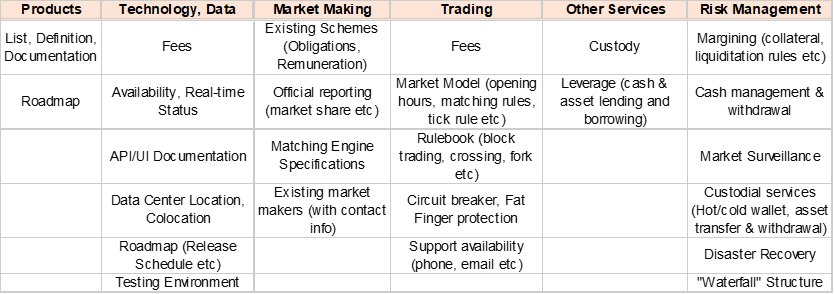

Next chapter, trading. Surely one needs to be well-informed about an exchange to be able to trade smartly. Like before, below is a non-exhaustive list of things you might want to know before transacting:

All in all, we are getting to the core of what an exchange is. There are very few cells in that table that are not highly relevant to the quality of service the exchange is able to deliver its clients. You might be tempted to consider some of those buckets are for professionals only, and that is indeed absolutely true. Then again, if professional traders conclude their due diligence favorably, chances are that any and all market participants will experience a higher quality of service.

Is that mass of information readily available from traditional exchanges? Absolutely, it may not be 100% present on their web site, but it is available to clients and qualified prospects. Is it readily available for crypto exchanges? No, not by a long stretch. Should it be? Insofar as it directly relates to the way orders, executions, risks are handled, there is little doubt here — it should be timely, accurate and exhaustive.