Last autumn I had the pleasure of giving an introductory course on financial risk management at IAE in Bordeaux. The purpose was to provide students with a general understanding of what financial risk looks like, and what it means to “manage” risk.

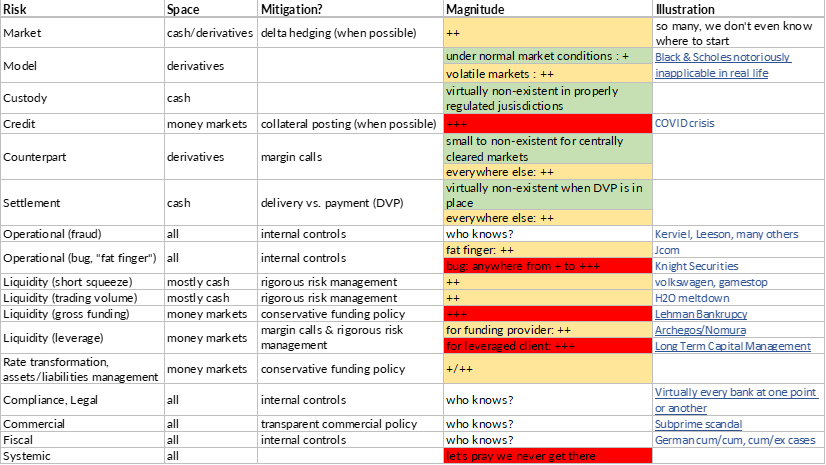

Naturally, as part of the course, I had to offer a typology of financial risks i.e. a list as exhaustive as possible of all risks, their magnitude, likelihood, and to some extent the way to mitigate them.

The result is the table below: it is naturally a simplification, but not an excessive one. Listed are the risks by type, with the space of instruments they apply to, some simple ideas about possible mitigation, the first order of magnitude, and examples of things gone bad whenever possible:

The magnitude scale is as follows (applied to capital at risk, whether it is a nominal amount for cash products or notional amounts for derivatives):

- + (very small to small): a fraction of a percent to a few percents

- ++ (medium to significant): a few percents to a few tens of percents

- +++ (high to very high): up to 100% and beyond. The vital prognostic of the firm may be engaged

- who knows? this one is exactly what it reads, possible losses range from trivial to life-threatening

The individual links do not appear in the image, so here they are with underlying URLs:

- Black & Scholes notoriously inapplicable in real life

- COVID crisis

- Kerviel, Leeson and many others

- JCom

- Knight Securities

- Volkswagen, gamestop

- H20 meltdown

- Lehman bankruptcy

- Archegos / Nomura

- Long Term Capital Management

- Virtually every bank at one point or another

- Subprime scandal

- German cum/cum, cum/ex scandal

Now it is beyond the scope of this article to go deeply into each risk, but one remark is in order: the table above could be much redder, and was such in fact not too long ago. Indeed, many of the risks have turned out to be manageable because the industry has structured itself to address them. I have written before about the operational governance in capital markets, this governance is the result of a long slow evolution. A lot of money has been invested (and still is) into market infrastructure, to vent several types of risks out of the system.

A few examples to illustrate the point: independent clearinghouses, heavy regulation of depository institutions, SWIFT massaging infrastructure, standardized master agreements (notably from professional organizations such as ISDA, ISLA, ICMA, etc), delivery-vs-payment settlement to name but a few.

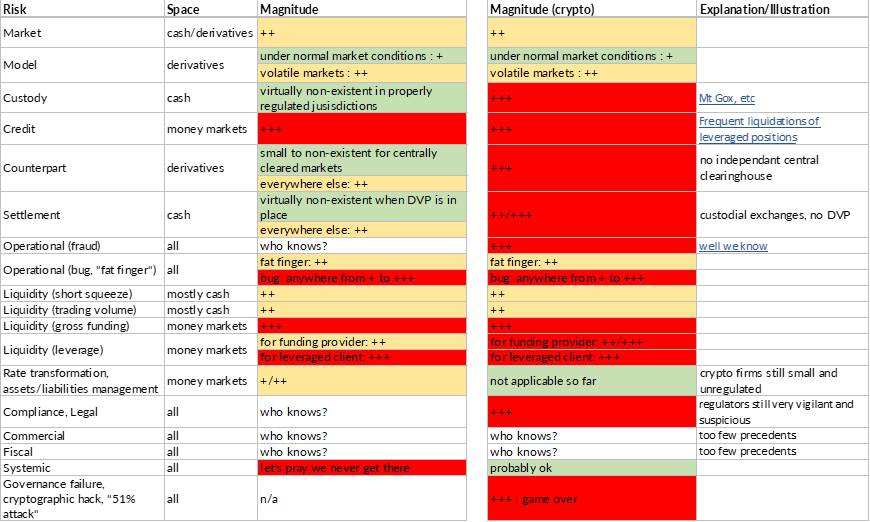

What’s the situation in the realm of digital assets? Are we better or worse in an ecosystem that is much younger, and not yet dominated by highly-capitalized international financial institutions? Supposedly fintech are nimbler and consequently more adaptable.

The table below summarizes the main differences (well, at least as I see them):

Like before the links have disappeared in the picture, here they are:

Naturally the above is subjective, and I am quite certain many bitcoin proponents would object. Regardless, there is little doubt that it is redder than the previous table, and for good reasons: most of the infrastructure in place in traditional markets doesn’t exist in crypto. For example, exchanges are “custodial” i.e. you need to deposit both fiat and crypto before you can trade. There is no single (cash) exchange in traditional markets that accepts deposits from its members and/or participants.

The question of settlement and money flows is addressed somewhere else in the industry (that’s exactly why clearinghouses have come to exist, and those do require deposits from the select firms they accept as members). Even when you settle a trade with a stable coin such as Tether, you still carry the specific risk of Tether. The same applies to derivatives: in the absence of a central clearinghouse, exchanges manage the entire process, and there can be no assurance for an investor that he will be able to recoup his funds should the exchange go under.

Reward doesn’t go without risk and vice versa. The reason why crypto is such a gold rush right now is exactly this: risk is high, widespread, and probably very poorly understood. Investors who made a lot of money should probably ask themselves: what risk did I really take? Am I out of the woods now? Which one(s) do I want to take going forward?

To end on a positive note, one risk has disappeared, and that’s for the better: the systemic one. If bitcoin went to 0, or if a large crypto participant went under, chances are the overall economy would not suffer much. This incidentally is why regulators worldwide still do not want to intervene. They are vigilant, suspicious because part of their mandate is to protect the “small” guy. But from a risk standpoint, they can still afford to let the crypto space mature and regulate itself.