More than 10 years after the creation of Bitcoin, and as the third “halving” has just taken place, the theme of inflation appears regularly in the digital asset camp. More precisely, it is the idea of an absence of inflation that is presented as disruptive and a guarantee of stability. The idea is interesting, but its application approximate. Let’s take a look at the issue.

- What is inflation?

The dictionary tells us: “Inflation is the loss of the purchasing power of money, which translates into a general and lasting increase in prices”. Put differently, a basket of goods and services that is worth €100 today will be worth more at a later time. Inflation is not good news for a consumer: all other things being equal, purchasing power mechanically decreases.

Inflation is an important psychological factor in consumption. It is because they are afraid of an increase tomorrow that many consumers buy today. Hence the idea that a fall in prices (“deflation”) should be avoided, since it acts as a brake on consumption.

- Inflation is a tax

Inflation is a tax that doesn’t say its name. It is profoundly egalitarian since all economic agents are affected equally, and profoundly unfair since those who suffer most are the low income earners whose erosion of purchasing power is often not compensated by an increase in income. But if we are indeed in the presence of a tax, is the State the beneficiary? Yes and no, we will come back to that.

- Inflation has two major sources

Broadly speaking, inflation occurs for two reasons:

- First, as a consequence of demand-led economic growth. The principle is simple and sound: demand for a good gradually increases its price. At the scale of an economy, in periods of strong growth all prices are pulled up. Wages are then likely to be adjusted upwards as well, either because corporate profitability allows it, or because the labor market tightens when unemployment falls. This is the inflation that everyone dreams of.

- The other form of inflation is an increase in the money supply. Literally, if tomorrow the stock of money increases by 10%, the price of goods and services in the economy will mechanically increase by 10%. This inflation is much more insidious, its effects are not always beneficial, and it can exist in the absence of economic growth. In this case, it will be harder for wages to keep up with prices, since businesses do not see a solid demand for their products.

Understanding inflation therefore also means looking at the money supply, i.e. the mass of money in circulation. And what is the pillar of money creation? Credit. It is therefore impossible to talk about inflation without talking about credit.

- Inflation and credit

An accommodative monetary policy, i.e. a policy in which credit creation is facilitated (e.g. by keeping interest rates low) is inflationary. Here lies the first of a consumer’s great contradictions: asking for an abundance of low-cost credit does not go hand in hand with low inflation.

“The link between inflation and credit is so strong that central banks are assigned the responsibility for maintaining price stability.”

The European Central Bank, like the US Federal Reserve, often comments on the subject: their consensus places beneficial inflation around 2%. Central banks must therefore steer monetary policy between two constraints: authorizing the creation of money (in the form of credit) to promote economic development, without falling into the opposite excess which would encourage inflation and erode purchasing power.

- Inflation and wealth transfer

If inflation is a tax, who collects it? Governments benefit from moderate inflation (in particular for the dilution of their debt, see below), but it is not a tax in the traditional sense, i.e. a mass of money collected by public authorities. In fact, inflation organizes a transfer of wealth between economic agents.

To my left are the bearers of money (notes, coins, current accounts etc), that is to say everyone. On my right the mass of borrowers — be they public or private, whatever type of debt they have contracted. Inflation is a transfer from the former to the latter. The wealth of the first group, expressed in monetary units, is devalued by inflation every year. For exactly similar reasons, the debt of the second group is also devalued through inflation every year. But this devaluation is a blessing: if I pay back €1,000 every month for 15 years, the purchasing power of that €1,000 falls over time. Today an effort of €1,000 per month is what it is, but after 15 years of inflation it is certain to be much less constraining.

In essence, this is the consumer’s other damnation: high inflation reduces purchasing power, but it also greatly increases his debt capacity, especially for the debt that dominates in terms of amount and duration — mortgages.

What is true for a household is also true for a state or a company: reasonable inflation makes it possible to absorb debt more quickly. Central banks are therefore in a difficult position: to let inflation run its course and allow governments to “dilute” their debt with the comfort that this represents for fiscal policy, or to actively fight inflation to safeguard purchasing power but with the rigor that this implies on interest rates.

- Inflation and interest rates

Is there a simple way to regulate the transfer of wealth that inflation organizes in an economy? Absolutely: through interest rates. To return to the example above, suppose that the €1,000 monthly repayment corresponds to an interest rate of 5% per annum on a loan of €240,000. Now suppose that my repayments are indexed to inflation, i.e. adjusted for inflation every year. If, for example, inflation materializes at 2.5%, I find myself paying back 7.5% per year, i.e. €1,500 per month instead of €1,000. This indexation protects the lender since at any time he or she captures the depreciation of purchasing power as overlay on the initial interest.

A sound monetary policy consists in controlling the general level of interest rates to regulate credit, the money supply and ultimately inflation. In periods of high inflation a central bank will raise rates, which has the immediate effect of slowing down credit and increasing the remuneration of lenders. However, raising interest rates and limiting credit also has negative effects on the economy, since businesses (and individuals) have more difficulty financing their investments.

These observations explain why many loans are indexed to variable rates. However, this is not the case for government bonds, which are mostly issued at fixed rates. Put another way, a government (fixed-rate) loan is much less protected against inflation than a variable-rate loan, especially over long periods of time. Real estate loans in France for example are massively fixed-rate, which in fact protects the borrower at the expense of the bank. In the US or the UK, mortgages are “adjustable-rate mortgages” (ARM), i.e. loans with adjustable rates, allowing financial institutions to protect themselves against inflation — at least to some extent.

- Bretton Woods

Is a world without monetary inflation possible? In fact it has existed recently, it was the world of the Bretton Woods accords (1944–1976). At the end of World War II, the great powers wanted a monetary system that would promote stability, in particular to avoid episodes of hyperinflation like Germany between the two wars. The Bretton Woods framework stipulated that currency exchange rates were fixed in relation to the US dollar, while the value of the dollar was fixed in relation to gold ($35 per ounce). This system of fixed exchange rates against gold prevented uncontrolled monetary creation on the dollar and consequently on other currencies.

“In Bretton Woods, a close control of monetary creation implied a strong constraint on credit creation. And a strong constraint on credit creation resulted in…a period of unprecedented stability.”

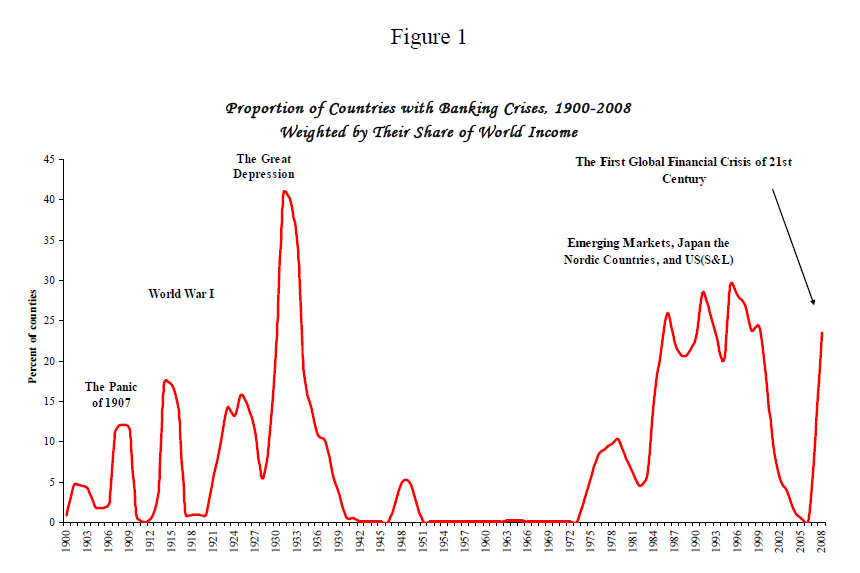

The following graph shows the percentage of countries in a state of financial crisis between 1900 and 2008:

Source: “Banking Crises: An Equal Opportunity Menace”, Carmen M. Reihnart, Kenneth S. Rogoff, NBER Working Paper 14587.

It is clear that the application of Bretton Woods corresponds to a period of calm that did not exist either before or after — even when there was lasting peace. From this the conclusion that uncontrolled money creation linked to credit creates at least as many problems as it solves is only a step away. After Bretton Woods, most financial crises had their source in the encounter of massive indebtedness and capricious economic activity.

- Inflation and digital assets

Most digital assets have the characteristic of having “hard-coded” inflation in their protocol. This is the case for bitcoin, ethereum and many others. This inflation is of a monetary type, i.e. it does not correspond to an increase in prices, but to the creation of money. As no other inflation is possible since there is no central bank to regulate the quantity of money, it follows that there is no creation of credit on these protocols. To borrow, one must therefore find someone who lends the assets he owns. Similarly, there is no room for a commercial bank in these systems, since their main function in real life is not account keeping but credit creation.

The claim that digital assets offer protection against inflation is absolutely correct. But it comes at the price of a lack of credit. In an economy based on a digital currency, consumer-citizens could find that there is no inflation linked to money creation (beyond the one coded in the protocol). They might find that there is no bank to charge account fees, but they might just as well realize that getting credit to buy their home is a miracle. In a world where money supply is limited, getting credit is akin to convincing someone to lend you their savings. All borrowers are in direct competition with each other for a limited resource. Moreover, the absence of monetary inflation does not imply the total absence of inflation, only the second inflationary mechanism disappears. If a digital currency were available to buy oranges, the producer could very well decide to increase his prices on his own in the face of strong demand.

- Conclusion

While it is quite true that the absence of inflation offers security for holders in relation to national currencies, this assertion must be supplemented by the observation that an economy based on a digital currency would be nothing like the one we have today. In the absence of credit, governments (and businesses and individuals) would see their indebtedness capacity seriously eroded. What would be the best use of a unit of currency available for borrowing? A car, a factory, the public deficit? And what would be its price? What interest rate would have to be paid to the bearer of this unit for him to accept the credit risk of a given borrower?

Economies of this type have existed throughout human history, including during periods of industrialization. There is therefore no theoretical impossibility for their reappearance. But the world today is so overburdened with debt that it is difficult to imagine such a return.