This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

FTX Post-Mortem Analysis – Why Transparency Matters?

By Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

November 2022

“In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity”

Sun Tzu – 500 BC

This quote by our spiritual father, Sun Tzu, has never been more true in the crypto ecosystem as we all battle to survive the most significant blow ever to the nascent industry. FTX’s bankruptcy was described as crypto’s Lehman Brothers moment, or as more evidence came to light, more “Enron” than “Lehman” moment. Trying to cover this story as it unfolded before our shocked eyes was like trying to catch a bullet bare-handed. This article provides a preliminary post-mortem analysis of where the situation stands today. Unfortunately, we sincerely believe that we have only seen the tip of the iceberg, and we brace for many more casualties to be affected in the near future. We have already covered in SUN ZU Lab’s weekly insights (here & here) the story’s timeline and the significant headlines surrounding it. We will therefore move directly into a more technical analysis.

As a reminder, FTX and Alameda Research constituted the bulk of ex-crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried’s empire. The former being the exchange arm and the latter being the trading firm.

Understand the man to understand his actions:

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) had a reputation for being very smart and a highly talented trader. However, as more revelations come to light, we are convinced now that his supposedly spectacular trading returns (as well as some of his peers) were mainly driven by 2020 and 2021’s bull run. His crypto empire’s implosion is due instead to his betting big philosophy! A leveraging strategy mainly fueled FTX and Alameda’s stratospheric rise in the last two years via deceptive fundraises and financial engineering before eventually using plain fraud, as was revealed by the preliminary investigation.

In this Twitter thread, we get an interesting glimpse of SBF’s motives behind creating FTX; he explains, among others, that he was deeply frustrated by two things in the way other crypto exchanges operated. Contrary to TradFi, where an exchange focuses on managing its order book matching engine, leaving margin handling to the clearing house, a crypto exchange has to handle both responsibilities. He was therefore losing millions from what he called “socialized losses”, where the collectivity ends up paying the losses of a liquidated negative account. The second reason was that he viewed BTC’s price as being hit every time it suffered selling pressure from a cascade of liquidated accounts, which wasn’t fair from his point of view.

He initially addressed white papers proposing new ways of functioning to other exchanges before creating FTX as a new crypto derivatives exchange where, we cite: “The entire margin system is reworked to a way almost no exchanges in crypto work. We can take huge size & also have lots of leverage & have a solid blocker against ever having clawbacks.”

A trending video of Alameda’s CEO Caroline Ellison resurfaced where she was saying: “Being comfortable with risk is very important. We tend not to have things like stop-losses, I think those aren’t necessarily a great risk-management tool. I’m trying to think of a good example of a trade where I’ve lost a ton of money … well, I don’t know, I probably don’t want to go into specifics too much.”

We can see a recipe for disaster starting to take form.

A complicated SBF-Ellison / FTX-Alameda love story

Alameda Research and FTX were supposed to be entirely separate entities in theory. We instead learn that Alameda’s CEO Caroline Ellison has dated at times SBF. More shockingly, several top execs from FTX and Alameda lived in the same luxury penthouse in the Bahamas, where Ellison was rumoured to have access to FTX screens showing client trades. A recent Wall Street Journal report indicates that Alameda was frontrunning FTX token listings. Between the start of 2021 and March 2022, the trading firm held $60 million worth of 18 different tokens that were eventually listed on FTX.

This intimacy could also explain why SBF later allowed customer funds to be used to pay for Alameda’s loans, building a software backdoor to outwit FTX compliance systems.

FTX and Alameda’s Balance Sheets were bad, very bad!

The massive bank run suffered between November 6 and 11 drove FTX and Alameda eventually to the ground, and the word bank is chosen wisely as it appears FTX was more a bank than an exchange! They suffered as much as $6 billion of withdrawals in the final 72 hours, except they didn’t have customers’ money as FTX had loaned it to Alameda, which used it to make venture capital investments!!

Let us stop a moment on the last revelation. Every first-year finance student could tell you to never, never use extra-short-term liabilities (client funds, with a theoretical maturity of 0) to finance the riskiest and most illiquid investment in the spectrum (VC investments, with an expected maturity higher than ten years).

Ellison explains in an interview with the New York Times that lenders moved to recall their loans around the time the crypto market crashed this spring. But as the funds that Alameda had spent were no longer easily available, the company used FTX customer funds in an emergency procedure to make the payments.

Let’s go back first to where troubles began to appear. Anyone remotely familiar with the hedge fund space knows that the financials (P&L and Balance Sheet, among others) are protected at all costs. The fact that Coindesk managed to put their hands on that “secret sauce” leaves a place for a plethora of conspiracy theories. We refrain from venturing into that territory.

On November 2, CoinDesk published an article highlighting the following facts from a private document they reviewed:

- As of June 30, 2022, Alameda’s assets amounted to $14.6 billion. Its single most significant asset was a $3.7 billion pile of “unlocked FTT” and $2.2 billion of “FTT collateral”.

- Its c. $8 billion of liabilities are dominated by $7.4 billion of loans, but we also find $292 million of “locked FTT”.

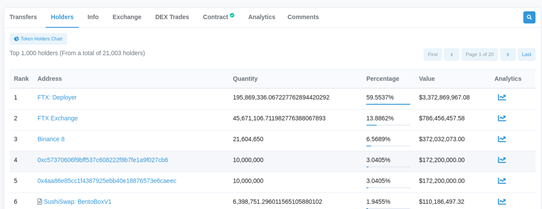

To put things into perspective, this puts a total of $5.8 billion in FTT tokens on Alameda’s balance sheet as of June 30. The market capitalization of circulating FTT was around $3.3 billion that day. Indeed, a quick look at FTT’s page on Etherscan shows that over 74% of the token’s total supply is held by two addresses belonging to FTX and Alameda.

This partial information meant that most of Alameda’s net equity was comprised of FTT tokens, printed out of “thin air” by its sister company FTX.

In a volatile and fragile global crypto environment, rumours were quickly forming about how SBF could be just another flywheel / Ponzi scheme magician! Here is what we mean by a flywheel scheme in crypto:

- Create a token

- Artificially pump its price (wash trading through a market maker)

- Mark the artificial gains in the balance sheet

- lure the community and investors with “realized” gains

- Raise capital through equity sales, ICOs or loans

- the hype continues to fuel the token’s price, and the loop continues!

The fears were extreme, especially since the Celsius bankruptcy and the CEL token explosion still haunt most of us. Celsius was a multi-billion dollar crypto lending firm, or Ponzi scheme, which was destroyed in part by its own token, CEL!

As it appears, this is exactly what SBF was doing with some of his investments, known as “Sam coins”, including Serum, Raydium and FTT.

The way it would work with our exchange/trading firm duo is that Alameda would fund a project at a $50 million fully diluted valuation (considering the total number of tokens to be issued) with $5 million, for example. FTX would then list the token on its exchange, releasing only a tiny fraction of the total tokens to the market. Given the illiquidity of this token, Alameda could easily deploy a few millions to artificially inflate the fully diluted valuation 100x, increasing the stake’s value on its books to $500 million. This inflated figure is then used as collateral for borrowing purposes.

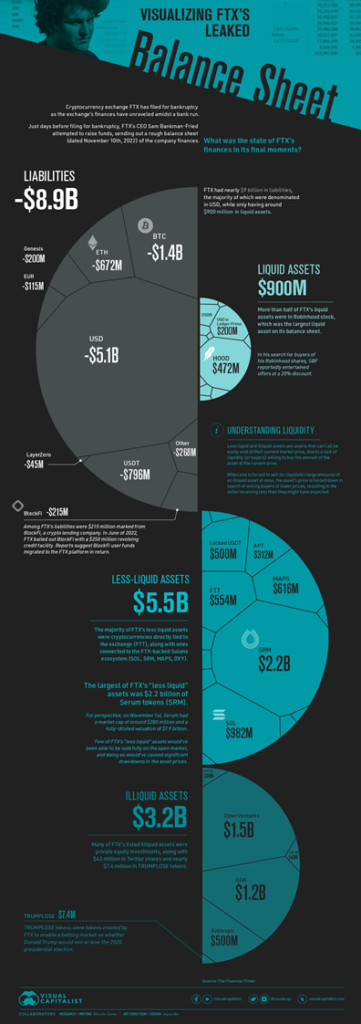

The Financial Times shared a copy of an FTX balance sheet dated November 10, shared with prospective investors one day before the company filed for bankruptcy.

Here is a visualization of this balance sheet provided by Visual Capitalist:

We fell from our seats when we first saw this balance sheet! And we wouldn’t put it better than Bloomberg’s Matt Levine:

“It’s an Excel file full of the howling of ghosts and the shrieking of tortured souls. If you look too long at that spreadsheet, you will go insane.”

Citing the FT, we learn that “A spreadsheet listing FTX international’s assets and liabilities, seen by the Financial Times, point at the issues that brought Bankman-Fried crashing back down to earth. It references $5bn of withdrawals last Sunday, and a negative $8bn entry described as “hidden, poorly internally labled ‘fiat@’ account”.

“Bankman-Fried told the Financial Times the $8bn related to funds “accidentally” extended to his trading firm, Alameda, but declined to comment further.”

When we look at the “less-liquid assets” category, the most considerable number is $2.2 billion of SRM, the Serum DEX native token (we will talk later about Serum). This is a clear example of the flywheel scheme described above in the article. As of November 17, CoinMarketCap shows a $70 million market cap for SRM (market cap of circulating tokens) against a $2.7 billion fully diluted market cap (theoretical figure taking into account the token’s max supply). The FTX team are basing their $2.2 billion valuation on an impossible illiquid scenario.

Okay, but one big question remains: how did they manage to burn through more than $10-15 billion of “realized” profits?

In our eyes, the bad VC investments and mishandling of client funds don’t explain alone the $8 billion hole in the balance sheet, especially when taking into account FTX and Alameda’s extremely profitable history due to high trading fees and lucrative venture deals. The only plausible explanation we see is that Alameda was bleeding money for a long time in 2022’s harsh bear market and possibly long before that, slowly decaying from its market-neutral market-making strategies into taking losing directional bets.

This seems to be exactly what we learned from a recent motion filed in the Delaware district court handling the bankruptcy procedure. The entities’ 2021 tax returns collectively showed a net operating loss carryover of $3.7 billion, meaning that the main entities (FTX & Alameda) had posted that much in losses since their inception. This completely contradicts the image SBF was circulating of his businesses and is quite shocking when considering that several competing crypto exchanges and trading firms, such as Wintermute or Coinbase, have realized significant gains over 2020 and 2021’s roaring crypto bull runs!

We end this paragraph on the wise words of newly appointed FTX CEO John Ray III: “Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here. From compromised systems integrity and faulty regulatory oversight abroad, to the concentration of control in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals, this situation is unprecedented.”

The biggest winners & losers:

Losers:

It is tough to choose one big loser from the FTX fiasco. There is obviously SBF himself, whose net fortune went from $26 billion at its peak to less than $1 billion. FTX employees are set to lose big, having most of their wealth linked to the exchange. VC and institutional investors have bet big on the disgraced young prodigy: between 2021 and 2022, SBF raised more than $1.5 billion from esteemed investors such as SoftBank, Sequoia Capital, Temasek, Tiger Global Management, Paradigm or the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. Without forgetting the more than a million creditors still waiting to see how this insolvency will be unpicked. It was typically revealed in a court filing that FTX owes almost $3.1 billion to its top 50 creditors.

We want to focus on the Solana ecosystem as one major casualty. The Solana Foundation declared days after the bankruptcy that it held 134.54m SRM tokens and 3.43m FTT tokens on FTX when withdrawals went dark on November 6. Those assets were worth around $107m and $83m one day before the freeze. It also held a 3.2 million common stock ownership in FTX.

As we can see, Solana and FTX maintained deep financial ties. The problem gets bigger when considering Serum, a DEX created by SBF and at the centre of much of Solana-based DeFi. SBF even went on to call Serum the “truly, fully trustless” backbone of Defi on the Solana blockchain. DeFi protocols across the Solana ecosystem were rushing to unplug from Serum after the post-bankruptcy hack at FTX. It was reported that the true power over Serum rested with FTX and SBF, which continue to hold the program update authority keys. This led the Solana community to move to create a new version of Serum that they could govern without influence from FTX.

The total value locked (TVL) on the Solana network has seen a 70% drop in November 2022 alone, reaching lows of $300 million from a $10 billion peak in November 2021. SOL is down more than 60% since the start of the month and the Coindesk article release.

In a previous article by SUN ZU Lab titled “What is Tokenomics and why does it matter?”, we interestingly took the Solana case study to highlight the importance of good governance practices that protect users. One of the main questions we left our readers to reflect upon was the following: Is it really that decentralized? – We now have our answer!

Winners:

There aren’t many winners from this situation, except maybe DEX’s, which are seeing an impressive peak in interest since FTX’s implosion. Uniswap, in particular, has risen to become the world’s second-largest venue for trading Ethereum, having recorded more than $1 billion in ETH trades in 24h, surpassing Coinbase (c. $0.6bn). Since the news that Binance was about to bail out FTX, DEXs around the crypto ecosystem saw $31 billion in trade volumes, with Uniswap alone accounting for $20 billion.

We want to highlight, however, that while DeFi’s “permissionless, trustless self-custody” ideology seems to be winning short term, we don’t bet a lot on new institutional money going directly into DeFi, mainly for KYC and AML reasons, among others.

How did crypto markets react to all this?

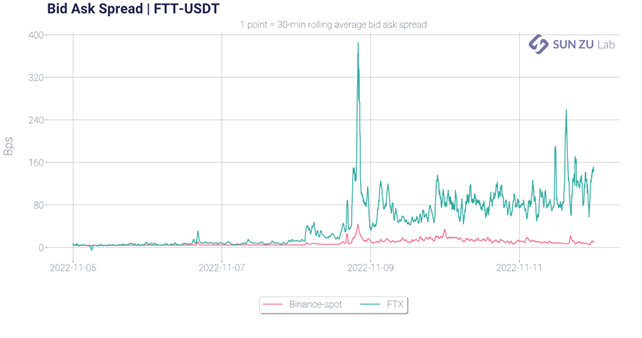

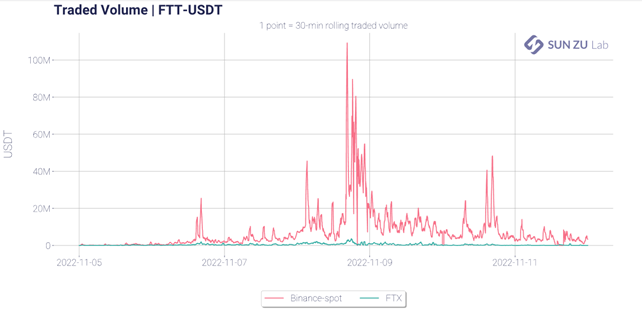

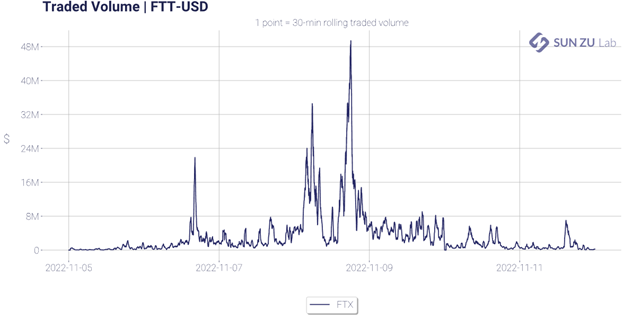

Whether we analyze crypto markets from a price, bid-ask spread or volume perspective, we see that the turning point in FTX’s downfall was the announcement of Binance’s non-binding offer to buy its rival (11/08/22 around 5 PM UTC). It was the first major event that worried the markets that something was off. FTT’s price dropped by more than 80% in the following hours, while bid-ask spreads on FTT briefly reached 400 bps.

Could we have seen this coming?

Yes! We have already voiced our opinions and concerns over crypto risk assessment in general and how crypto venues should be managed and audited in these previous articles: “Everything you’ve always wanted to ask your crypto exchange” and “Crypto Risk Assessment: Way to Go“. FTX was ranked among the top crypto exchanges, just days before its fall, by major industry players, non of which were able to underline the significant governance, operational or counterpart risks surrounding FTX and Alameda. We believe the crypto industry now has few shots “to get this right” after this spectacular failure.

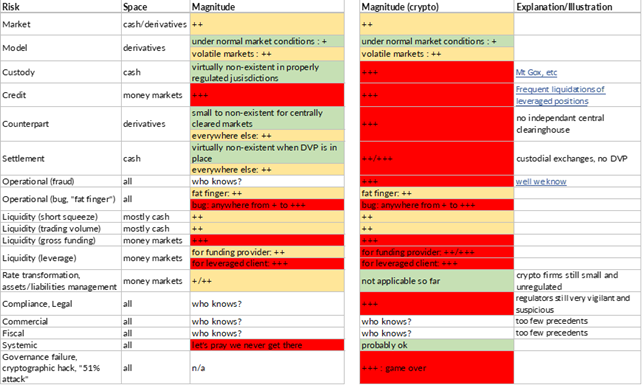

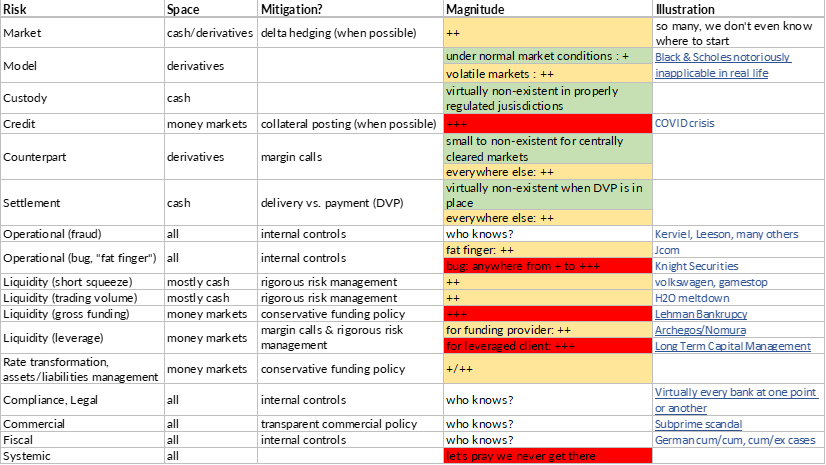

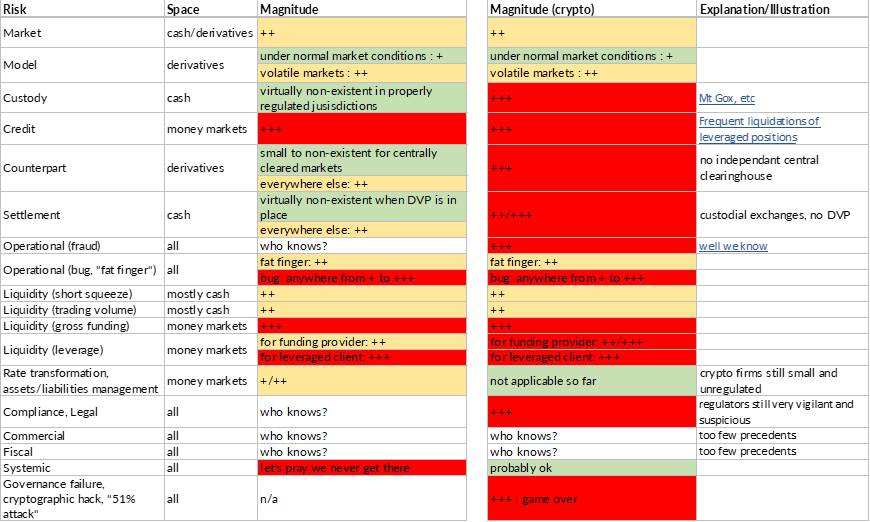

We put the emphasis again on this table from the Crypto Risk Assessment article, which summarizes, in our opinion, the significant risks that should be closely monitored and audited regarding crypto exchanges.

The magnitude scale is as follows (applied to capital at risk, whether it is a nominal amount for cash products or notional amounts for derivatives):

+ (very small to small): a fraction of a percent to a few percents

++ (medium to significant): a few percents to a few tens of percents

+++ (high to very high): up to 100% and beyond. The vital prognostic of the firm may be engaged

who knows? This one is exactly what it reads; possible losses range from trivial to life-threatening

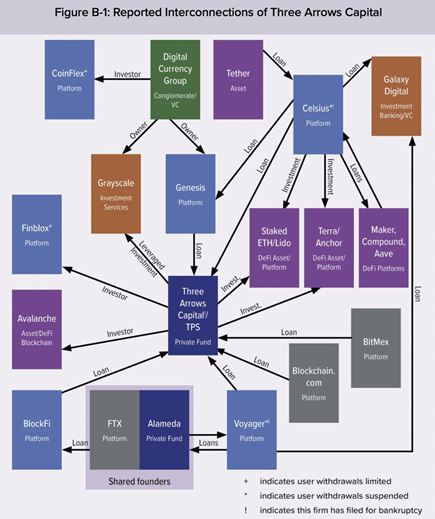

We also highlight this chart from the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s (FSOC) latest report, released in early October 2022. It highlights the major parties related to loans or investments made by 3AC, where we can see all the now-troubled actors following the explosion of the Terra ecosystem.

Where do we see things going from here?

For one thing, the FTX and Alameda implosion will hurt crypto liquidity badly. Alameda was one of the largest market makers in a space dominated by a handful of actors, among which we can cite Wintermute, B2C2 or Genesis. More disturbing, 56 market makers and fund managers reported FTX exposures of up to $500 million in an invite-only Telegram chat reviewed by TechCrunch.

As of November 24, the expanding list of FTX casualties now accounts for crypto-giants Genesis and Grayscale, BlockFi, Gemini, Multicoin and CoinHouse to cite a few. Genesis Global announced having lent around $2.8 billion to various crypto firms, including large loans to its parent company DCG. It confirmed that it had hired investment bank Moelis & Co to explore how to shore up its crypto-lending business’ liquidity and address clients’ needs days after halting withdrawals.

The bankruptcy procedure will surely be a long, drawn-out court case in which depositors will try to recoup their losses. But at which cost and after how many years?

FTX’s failure is unsurprisingly sparking a massive regulatory response, with several US state and federal agencies launching or expanding investigations into the company, including the DoJ, the SEC, the Securities Commission of the Bahamas and the Bahamas’ Financial Crimes Investigation Branch. More globally, crypto regulation in most markets has been slow to materialize. We see that changing in the wake of these recent events, with MiCA regulation in Europe heading for final approvals in 2023.

As this situation continues to evolve, we can’t yet draw final lessons and conclusions, except repeating our core message and belief at SUN ZU Lab: liquidity and transparency are core constituents to every efficient market worthy of the name. Remove one or both, and even “Too Big To Fail” giants start to shake.

We would be happy to hear your thoughts. You can address questions and comments to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboard & API stream or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.

Opinion article: How a simple “heads or tails” game illustrates the importance of transparency in crypto markets?

By Stéphane Reverre and Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

November 2022

Crypto will always fascinate us. Who would have thought that we would manage to find a link between a famous 60’s American television game show, a Kevin Spacey poker movie, a heads or tails game and crypto market liquidity transparency? But here we are at SUN ZU Lab, always striving to push the boundaries of common perceptions.

The Monty Hall problem is a probability puzzle named after the host of the American game show “Let’s Make a Deal”. The problem was initially posed and solved in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975. It became famous after Parade magazine columnist Marilyn vos Savant responded to a reader’s question regarding it in 1990. Professor Micky Rosa (Kevin Spacey) later uses it to clarify his point about the Change Variable’s importance in the famous movie Las Vegas 21, released in 2008 (link).

It goes as follows:

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

Counterintuitively, the odds are not at all 50-50. You have a 2/3 (67%) probability of winning by switching doors!

We would not explain why this is true using conditional probability and Bayes theory (interested readers can check the paper in the reference section). Let’s instead see the problem from the following perspective:

- There are 10 doors to pick from at the beginning

- You choose one door

- Monty looks at the 9 others, finds the goats, and opens all but 1

Do you remain with your original door (1/10 chance of winning) or the other door, which was filtered out from 9 other possibilities?

Monty is improving your 9 choices set by removing 8 goats. Once he’s done “cleaning”, you are left with the top door out of 9 for you to choose from.

The question asked differently is: Do you want a random door out of 10 (initial guess) or the best one out of 9?

Now coming back to our initial pain point, crypto liquidity transparency, the question becomes:

As a professional crypto user, do you want one random liquidity venue to execute your trades or the best of 9 liquidity venues, carefully analyzed and filtered by an independent entity?

We give another example to illustrate our opinion better. Let us consider a game with three coins: one is two-headed, the second is a biased coin that shows heads 75% of the time, and the third is unbiased. One of the three coins is chosen randomly and tossed. What is the probability that it was the two-headed coin?

Without additional information, the chances of getting the two-headed coin are 1/3 (33%). Knowing that the tossed coin showed heads, the probability becomes 4/9 (44%)!

The previous probability is computed using Bayes theorem. Let E1, E2 and E3 be the events of choosing a two-headed coin, a biased coin and an unbiased coin, respectively. A is the event that the coin shows heads:

P(E1|A) = P(E1).P(A|E1) / [P(E2).P(A|E2) + P(E3).P(A|E3) + P(E1).P(A|E1)]

P(E1|A) = (1/3) / (3/4) = 4/9

Without this crucial information, the player would be at a clear disadvantage, as it is not “fair” to play against a game master that dissimulates essential information.

What we refer to in the previous example is non-other than information asymmetry. This problem has been studied thoroughly in contract theory and economics, and regulators try to eradicate it as much as possible. Information asymmetry creates an imbalance of power in transactions, leading to severe market inefficiencies such as moral hazard risks or the establishment of monopolies of knowledge.

The general idea, put simply, is the following: Information is King! The more you know, the better (crypto investment) decisions you make. That’s why transprency is key.

Between an opaque liquidity venue on which no information is available and another independently audited for a significant period, the chances of taking the best decision are far from 50-50. While past performance is not a guarantee of future results, you should at least be able to tell if your crypto liquidity venue is sharing necessary information with you. We are convinced at SUN ZU Lab that as the crypto market matures, the need for transparency-enhancing players will materialize to the point of absolute necessity.

We would be happy to hear your thoughts about transparency in crypto markets!

Questions and comments can be addressed to: founders@sunzulab.com

References:

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboard & API stream or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.

Opinion article: Why has liquidity become a question of survival for crypto venues?

By Stéphane Reverre and Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

October 2022

Having already covered in this previous article the basics of market liquidity, with a focus on crypto markets, we decided to turn our attention to a new question: Has crypto liquidity become a question of survival for crypto venues? Indeed, the current harsh global macro environment has caused a liquidity crunch across all asset classes, especially risk-on assets such as cryptocurrencies. This situation has left crypto venues with no choice but to enter a race-to-zero on trading commissions to try and protect their market share, at the expense of revenues. Is this situation sustainable? When and how is this deadly spiral going to end? This is indeed a question of survival: trading venues and intermediaries cannot afford not to monitor their liquidity against their competitors. It is fast becoming a significant competitive advantage, probably the only one that will allow a favorable re-pricing of commissions.

Amid an overall bearish year for cryptocurrencies and other risk assets, Binance-US “surprised” the crypto ecosystem recently by adopting a zero-commission policy for BTC and other cryptos. The announcement led to an all-time high of more than 600K BTC traded on Binance the day the policy took effect, while Coinbase shares fell by almost 10%.

The effect on Coinbase’s shares is not a surprise. Like any exchange, it has historically relied heavily on fees from trading volumes. Unfortunately, those have declined in sync with prices, creating instantaneous and significant pain, leading all crypto exchanges to look for ways to diversify their revenue streams.

The zero-fee trading phenomenon is not an innovation by Binance; US neo-broker Robinhood first introduced it a few years ago. Major stock brokers soon adopted the disruptive business model shift, including Charles Schwab, Fidelity Investments or E*Trade Financial. Presumably, the measure will generalize in the crypto space, which will also create tremendous revenue pressure on non-exchange liquidity providers.

In TradFi this cannibalization of revenues has been addressed in different ways. For example, large established brokers are offering premium services such as wealth management. By contrast, Robinhood is a bare-bone online broker without much in terms of service to make up for zero-fee transactions. It had to implement Payment For Order Flow (PFOF) to generate revenues.

In the PFOF model, a broker routes its clients’ orders to market makers. The market maker earns a profit by collecting a spread between buying and selling prices, paying the broker in return for the right to fill the investors’ orders. PFOF came under a harsh spotlight in early 2021 after chaotic trading by a group of retail investors on Reddit led to the spectacular GameStop short-squeeze. This episode put Citadel Securities and Robinhood on the SEC’s radar for potential conflicts of interest on how retail investors’ order flow data is being used against them. According to Bloomberg, the largest US brokerage firms earned a combined $3.8bn in 2021 for selling their customers’ stock and options orders. Interestingly even service-rich brokers adopted PFOF: Charles Schwab racked up $1.7bn, followed by Robinhood with $974m, for which Citadel Securities accounted for 22% according to the company’s 2021 annual report (34% in 2020).

Two things should be noted about PFOF:

- Firstly, it is somewhat counter-intuitive. Market-makers provide liquidity, and as such take on risk in the form of inventory. To carry this risk, they are usually compensated by the beneficiaries. For example, EUREX (a European derivatives exchange) offers market makers commission rebates, which is equivalent to outright payments. The fact that Citadel and others are willing to pay to get the flow suggests that their liquidity-providing algorithm is entirely different from that of traditional market markers. Indeed it most probably doesn’t incorporate the same constraints. The natural question then becomes: who benefits most?

- Secondly, even if it’s an impressive number ($3.8bn), we don’t know enough to assess the economic value of PFOF to parties involved. Suffice it to say that retail trading flow is indeed a very rich source of information, as “bankable” as it comes. Capital market professionals have known for long that it is the “gold standard” of un-informed trading, offering tremendous low-risk opportunities.

What’s the relationship of the above with the original crypto introduction? Well, we venture one recommendation and one supposition. Under pressure on commissions, exchanges should consider liquidity as the “gold standard” of their future profitability. Hence the recommendation: “know thy liquidity”. Monitoring it and measuring it to assess, for example, its robustness across different market regimes should become a strategic objective.

As for the supposition: the same cause having the same effects, we should expect some form of PFOF to emerge in crypto markets sooner rather than later. All of which raises again the question of value creation, repartition and eventually transparency: of the value extracted, what should the “fair” partition be? Regulators in traditional markets have looked hard at this question, and no doubt they will also consider crypto soon enough – an excellent reason to look at it beforehand.

References:

- Crypto Exchanges Cut Fees to Gain Market Share From Rivals (WSJ)

- Coinbase shares fall after rival Binance.US drops spot bitcoin trading fees (CNBC)

- Charles Schwab, Citadel Securities, Robinhood report windfall on sales of investors’ order flow (Financial News)

- Robinhood Markets 2021 Annual Report

Questions and comments can be addressed to research@sunzulab.com

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboard & API stream or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.

The safe-haven hunt in 2022 : is Bitcoin the answer?

By Chadi El Adnani, Crypto Research Analyst @SUN ZU Lab

July 2022

We revisit in this article a question studied by Sun Zu Lab in 2020 during the financial crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic: did bitcoin resist the market downturn better than other assets in 2022, and would it have been strategically interesting for investors to shift some of their positions to bitcoin before the downturn? the answer to these questions is still negative, as it was the case in 2020. We study in this analysis the behavior of various assets over the year 2022, specifically bitcoin, ether, equity markets (S&P 500), bond markets (US interest rates) and gold.

This result does not constitute an absolute answer to the intrinsic value of digital assets, but rather provides insights into a specific situation.

Economic context

2022 has been marked so far by the Russian invasion of Ukraine which, added to an economic context already weakened by the Covid-19 pandemic, has accentuated the slowdown of the world economy which could enter a long period of stagflation (low growth and high inflation). According to World Bank figures, global growth is expected to fall from 5.7% in 2021 to 2.9% in 2022, significantly lower than the 4.1% figure announced last January. We cannot help but notice the very visible parallel with the 1970s stagflation period. The comparison is striking: persistent supply disruptions that fuel inflation (Russian gas shortages, the effects of the prolonged severe lockdown in China on various value chains, etc.), coupled with the end of a long period of very accommodating monetary policy in major advanced economies: key interest rates close to 0%; Fed balance sheet in excess of $8.5 trillion (35% of US. GDP, an all-time record), etc. Added to this are projections of a slowdown in global growth and the fragility of emerging and developing countries in the face of the urging need to tighten monetary policies to curb inflation.

In this unique context, we wanted to put ourselves in the shoes of investors to understand whether it is in their best interest to move from one asset class to another, and especially whether cryptos represent an effective safe haven in times of crisis. We model the S&P 500 by its most liquid ETF: Spider (ticker SPY, NAV as of 06/17/22: $378 billion). Gold is modeled by its most liquid physical ETF (ticker GLD, $63 billion NAV). U.S. government bonds are modeled by the iShares 7Y-10Y ETF (ticker IEF, $18 billion NAV). Prices are closing prices and all execution issues are neglected. Access considerations are also neglected: the products used here are easy to access, anyone can open a securities account with an online broker or a crypto exchange in a few days. Data is extracted from Yahoo finance.

Finally, the « safe haven » concept reflects the idea that certain assets, financial or otherwise, provide a safe haven in the event of economic and financial turmoil. We often find in this category the US and German bonds, due to the almost absolute confidence in the strength of their economic fabric and their ability to always repay their debts. The Japanese Yen has often been considered a safe haven as well.

Performance

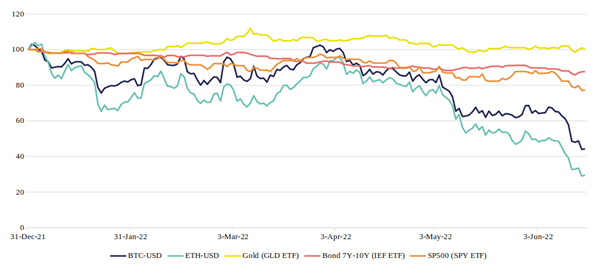

Without further ado, here is the relative performance of the 5 assets during 2022:

The numbers speak for themselves: only gold managed a stable performance in 2022 (0.2%), while BTC or ETH under-performed the bond and equity markets (-55.8% and -70.5% respectively).

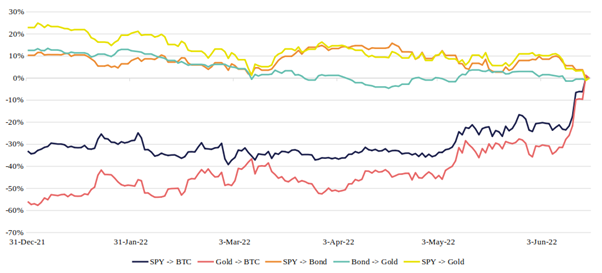

Another way to answer the original question is to calculate the “flight to quality” percentage of investors who switched asset classes. Indeed, this type of behavior is extremely common; cautious investors forecasting the increase in interest rates and inflation at the beginning of the year might have chosen to move some of their positions to safer assets, such as gold, US sovereign bonds, or even Bitcoin? Let’s look at the results:

The red curve reads as follows: investors choosing to switch their position on 12/31/21 from gold to Bitcoin would have realized a loss of 56% between 12/31/21 and 6/17/22 (compared to a situation where they would have remained invested in gold). The graphs show exactly how much gain/loss was received for switching, depending on when the switch took place.

It appears that the choice to “pivot” from another asset to BTC has never paid off in 2022. Gold, on the other hand, has well played its role as a safe haven, providing positive gains at almost any time of the year on S&P > gold and bond > gold pivots.

Volatility

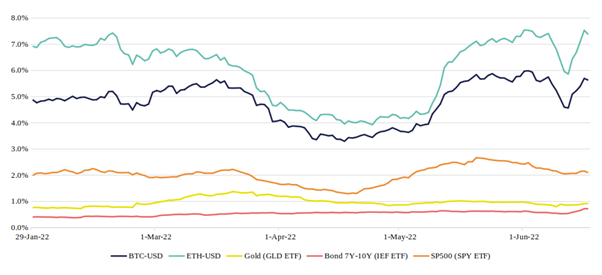

Rather than analyzing the assets’ volatility as defined by the classic financial formula, i.e. the annualized standard deviation of daily returns, let’s look at a more intuitive measure: the intra-day variation. We compute the 30-day moving average of daily amplitudes for the five assets.

The graph shows that over the year 2022, Bitcoin and Ether have varied on average between 3% and 8% from their highest to lowest price on a single day. In contrast, the S&P 500, gold and bonds only vary by 1% to 2.5% (or even less). Investors should keep in mind then that the amplitude of movements in crypto markets is 4 to 5 times greater than in traditional markets, which requires careful monitoring to deal with these risky assets.

Liquidity

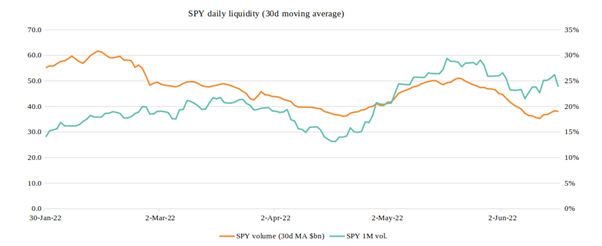

Finally, let’s analyze liquidity as characterized by daily volumes. This is a post-trade measure of liquidity, i.e. the liquidity that has been achieved through transactions. We could also study a pre-trade measure: the liquidity available before execution in the exchanges’ order books , which is a little more complex to compute.

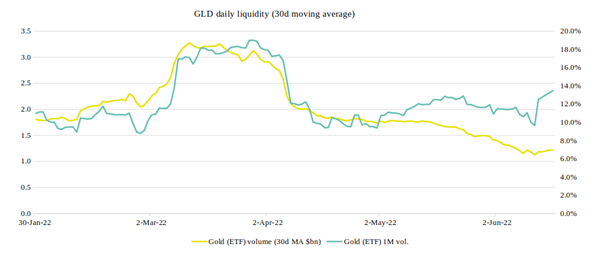

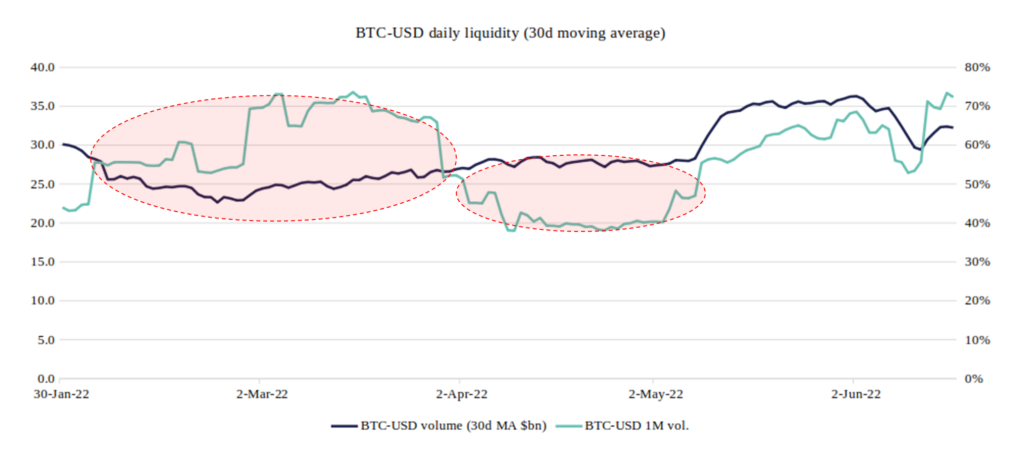

The graphs below show average trading volumes (30-day moving average) in 2022, with 1-month volatility (annualized standard deviation) as the second axis:

The S&P 500 ETF is one of the most liquid instruments in the world, with $30 to $60 billion traded every day. The causal relationship between volatility and volume is immediately apparent.

For the gold ETF GLD, we have daily trading volumes between $1 and $3.5 billion, but the causal relationship is still perfectly visible.

Regarding Bitcoin, we have first of all a confirmation of its very volatile character, with annualized volatility varying between 40% and 80%. This graph also raises discrepancies already made by Sun Zu Lab in 2020: it appears that the volatility/volume causality is still not respected, with peaks of volatility in February-March that are not accompanied by any increase in volume, and on the contrary periods like April when the volume seems to grow by itself!

The two circled areas on the chart are anomalies, likely due to the fact that the officially announced volumes are greatly overestimated and that the magnitude of phantom volumes varies over time. The S&P 500, gold and the bond ETF, not included here, show a rather stable “structural” liquidity: when the volatility peaks stop, the average volume goes back down to a base level.

Conclusion

The answer to the question “is BTC a credible alternative to the volatility of traditional markets?” is negative, again, over the year 2022. Unquestionably, gold and sovereign bonds are still the “safe haven” they have been for a long time. On the other hand, the liquidity of bitcoin (and ether) is still problematic; the volumes traded do not follow the same logic expressed historically by investors in the traditional markets.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a French Fintech that aims to become the leading independent provider of digital asset market quantitative analytics tools and services. Leveraging the founding team’s 70+ years of experience in international capital markets and trading technology, SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with unprecedented liquidity analytics in the form of quant reports, dashboards, real-time augmented data feeds, and bespoke studies.

Demystifying the Terra debacle

By Stéphane Reverre and Amine Mounazil

A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency whose value is “pegged” to the price of a reserve item, the US dollar being the most commonly used reserve asset. Stablecoins appeared for the first time in 2014, and have been gaining popularity since. Today, they are considered the backbone of the crypto ecosystem by providing an “on-risk” and “off-risk” alternative for cryptocurrencies. Moreover, their adoption is driven by the demand of traditional financial institutions and the larger crypto sector for a standard approach to leverage blockchain technology while avoiding related risks.

Thus, stablecoins address one of the fundamental issues with many mainstream cryptocurrencies: their extreme volatility, which makes them inadequate for real-world transactions. Altough competition is nothing new among stablecoins, “de-pegs” are an unwelcome and novel eventuality as different projects fight tooth and nail to source the liquidity required to keep their coins close to the promised pegged value ($1 most of the time).

In this piece, we first give a brief overview of stablecoin issuance, followed by an analysis of stablecoins from a macroeconomic standpoint, before introducing quantitative insights about the recent activity that led UST to depeg and spread contagion in the digital asset market.

A brief overview of stablecoin economics

To better understand the issuance of fiat-backed stablecoins, consider each stablecoin protocol as a financial organization similar to a bank with assets and liabilities. The reserve assets (monetary units or investment securities) and liabilities (issued tokens) are matched 1:1.

However, things are different in the case of crypto-collateralized stablecoins because of the volatility of the collateral. If the value of cryptocurrency reserves falls, the system may become undercollateralized. As a result, if liabilities are in dollar-equivalent, the 1:1 backing will not hold. One way to solve this problem, and to keep the entire system safe, is to make reserve assets significantly larger than liabilities (over-collateralize). Although their exact mechanisms differ, this is how the Maker (DAI) and the Synthetix

(sUSD) protocols manage their risk.

As for algorithmic stablecoins, they are based on the idea that maintaining the value of the stablecoin over time is possible through the right set of incentives offered to market participants, in response to market conditions. In other words, the protocol itself contains provisions to defend the peg directly, as in the case for Celo Dollar (cUSD) and TerraUSD ($UST).

When it comes to non-custodial stablecoins (i.e. stablecoin that do not hold physical collateral), there are five key hazards:

- Collateral (valuation issue)

- Data Feed (the system is unable to price itself)

- Administration (parameter failure)

- The Base Layer (the underlying blockchain fails)

- Smart Contract (a bug could lead to vulnerability and eventually insolvency)

Each of these can cause the stablecoin value to fall, possibly to zero. Because they are not formally backed by collateral, algorithmic stables like $UST are especially vulnerable to collateral risk. When there is a loss of confidence, such as when the general crypto markets falls, it may lead to a bank run or “death spiral”.

The robustness of a stablecoin depends on its ability to maintain the peg by reducing the spread between its “market value” and its “theoretical value“, i.e. the value of the currency the coin is pegged to. This ability is supported by two elements: the quality of market makers and the depth of the orderbook.

Stablecoin macroeconomics

In legacy markets, a currency peg is a means of securing a currency’s stability by tying its exchange rate to another currency. A notable example is the peg of the Chinese Yuan to the dollar, managed by the Chinese Central Bank, or the Swiss franc, whose peg to the Euro snapped in 2015. Currency pegs allow governments to develop a stable trading environment free of volatility, and to effectively operate an active control of monetary flows (e.g. balance of payments, foreign direct investment etc). As a general rule, government’s foreign currency reserves must be large in order to maintain a peg. This is because, if the government has to appreciate/depreciate its own currency, it may have to do so in the open market with its own reserves, in addition to traditional tools such as raising/decreasing interest rates.

A stablecoin is in essence a digital asset designed to keep its value by being pegged to a fiat currency such as the dollar or the euro, a commodity such as gold or silver, or another crypto currency. To keep the peg, the money supply of stablecoins is extended and contracted. When the price of a stablecoin rises in relation to the peg, the stablecoin’s money supply expands. Similarly, if the price of a stablecoin falls in relation to the peg, the stablecoin’s money supply contracts.

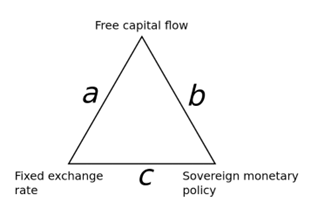

One recurrent risk for stablecoins, or any pegged currency, is the threat of an attack aimed at breaking the peg and profiting from price discrepancies (Soros’ 92). This risk has been present in legacy markets long before the emergence of blockchain technology and decentralised finance (DeFi), and is illustrated in modern economic theory by the concept of the “impossible trinity”. The impossible trinity (or unholy

trilemma) states that an authority (say a central bank) can only have two of the following at the same time, but never all three:

- Free capital movement (i.e. absence of capital controls): citizens of a country can diversify their assets by investing overseas, thanks to capital mobility. It also invites foreign investors to invest in the country by bringing their resources and expertise.

- A fixed foreign exchange rate (i.e. a peg): a fluctuating currency rate, which is sometimes influenced by speculation, can be a cause of larger economic unpredictability. A steady rate also makes it easier for households and businesses to participate in the global economy and develop long-term plans.

- An independent monetary policy: when the economy is in a recession, the said authority can raise and lower interest rates, and when the economy is overheated, it can cut the money supply and raise interest rates.

Source : Wikipedia

We turn now back to our crypto eco-system. It is crucial to understand the tokenomics behind both assets before diving into a quantitative analysis of the $LUNA and $UST debacle. The underlying protocol, Terra, operates with two tokens ($LUNA and $UST), and incorporates a virtual automated market maker (AMM). The objective is to keep those tokens in balance to maintain the $UST stablecoin’s peg. In addition to the “algo” part, Terra is supported by the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG) and its reserves.

Market participants can mint (e.g. create) $UST on Terra by burning (e.g. destroying) an equal dollar-amount of $LUNA and are incentivized to do so. Consequently, the price of $LUNA rises as the demand for stablecoins rises: the change in $UST demand dictates how much $LUNA must be burned. As this amount is subsequently burned, supply decreases.

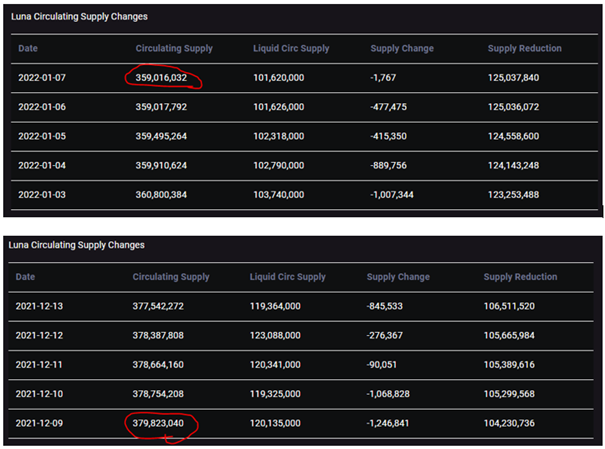

As it happens, $UST’s adoption since the end of 2021 has been parabolic, thanks to Anchor, Terra’s lending and borrowing protocol, which offered annual percentage yields (APY) as high as 19.5% on deposits. This, of course, has resulted in a reduction of $LUNA’s supply, which decreased by 5% in January 2022 alone:

Market activity quantitative insights

Now that we are somewhat familiar with the tokenomics of these protocols, we can better understand the market behavior by first reading market activity then looking at anomalies and microstructure analytics on [include venues & pairs].

Earlier this year, the Luna Foundation Guard (LFG) raised $1 billion through a sale of $LUNA (its native token) to form a $BTC reserve, in order to maintain Terra’s stability and fund future developments. The establishment of a $BTC reserve was meant to reduce the possibility of a death spiral. So, instead of having to mint $LUNA to arbitrage the price of $UST, users can now exchange $UST for $BTC on Terra.

In April again, the LFG acquired an additional 37,863 $BTC for ~$1.5 billion, while the Anchor APY was reduced to 18%. During the same period, a massive $UST sell-off happened on Curve and Binance resulting in a small depeg that was aggravated by the withdrawal of roughly $2 billion from Anchor. The unfavorable timing has led many participants to speculate this was a coordinated attack to drive the stablecoin to depeg in order to either cripple the Terra ecosystem or trigger some sort of contagion that would result in $BTC to dip.

Historically, every known stablecoin has broken its peg at some point. Moreover, statistical evidence* shows that $BTC volatility is statistically stable with a finite theoretical variance, whereas stablecoin volatility is statistically unstable and responds to $BTC volatility synchronously.

(*) “On the stability of stablecoins”, Journal of Empirical Finance, vol. 64, 2021, Grobys et al. – Source

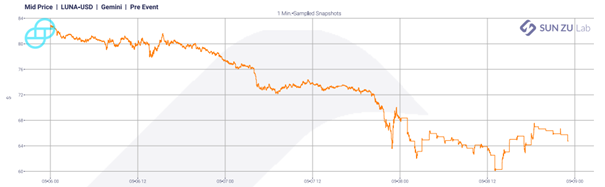

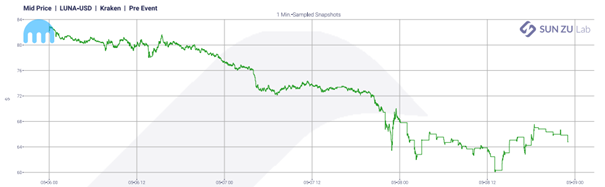

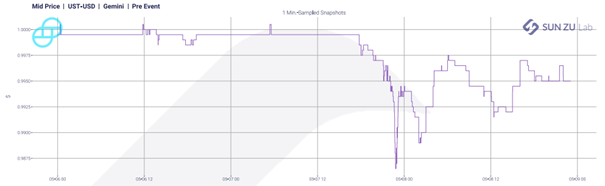

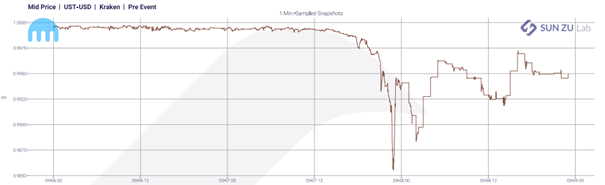

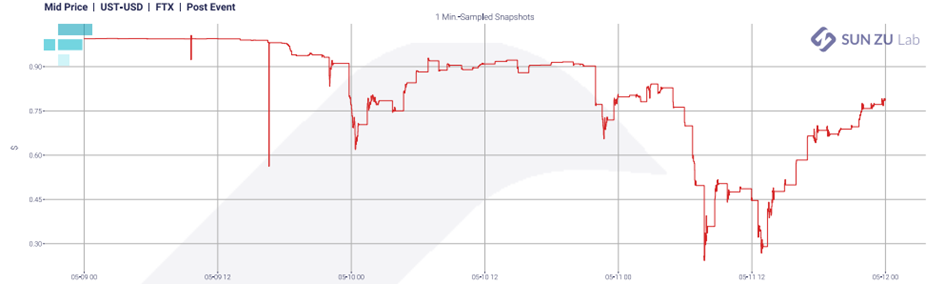

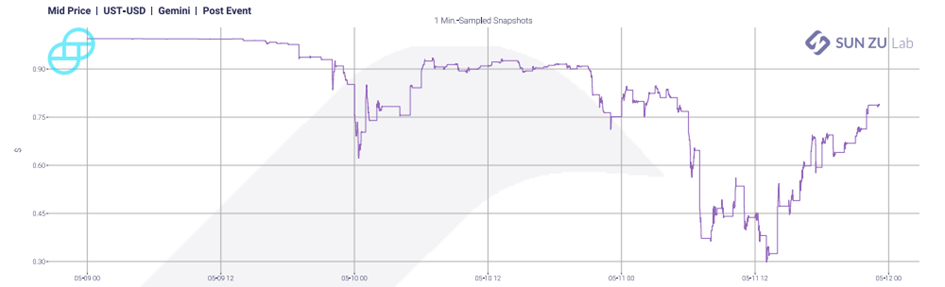

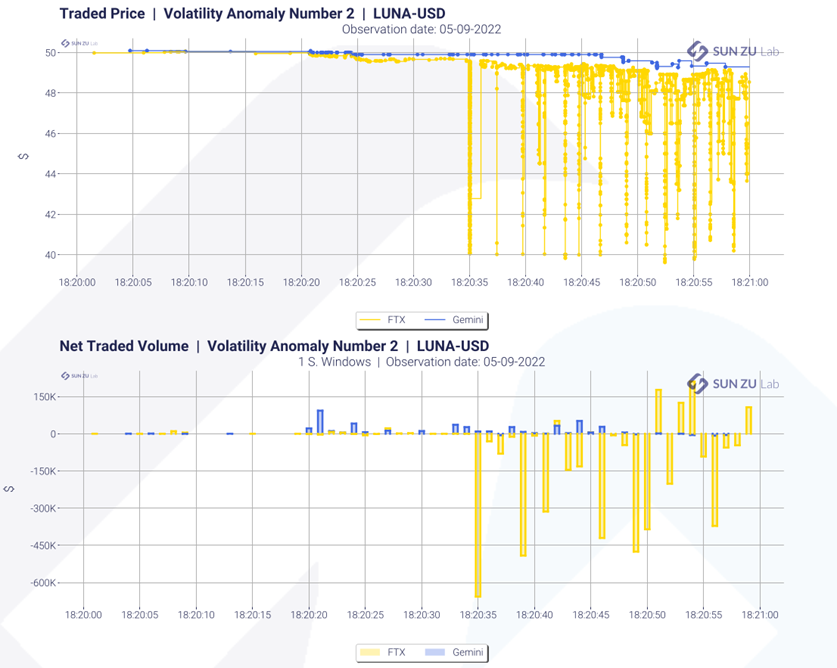

During the crash, the biggest volatility peak was observed at the beginning on May 9th at 6:20 pm. Many sale trades were observed, bringing the price down but immediately the market reacted and pushed the price back up, hence the high volatility. This selling pressure lasted exactly 1 min. The charts below show market activity for LUNA and UST on FTX, Kraken and Gemini over a few days prior to the crash (from May 5th to May 9th). Markets are still in “rebound mode” i.e., they tend to come back up even after severe down-moves, especially for UST:

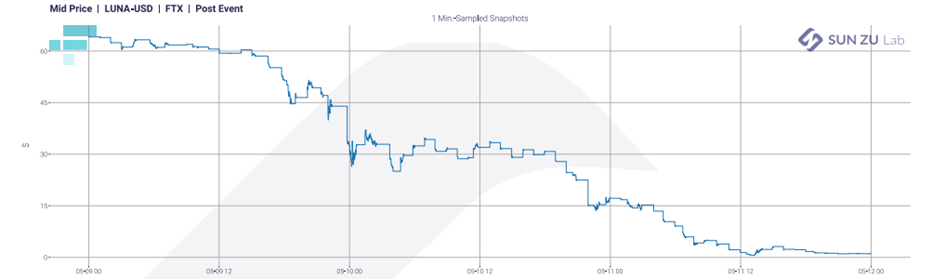

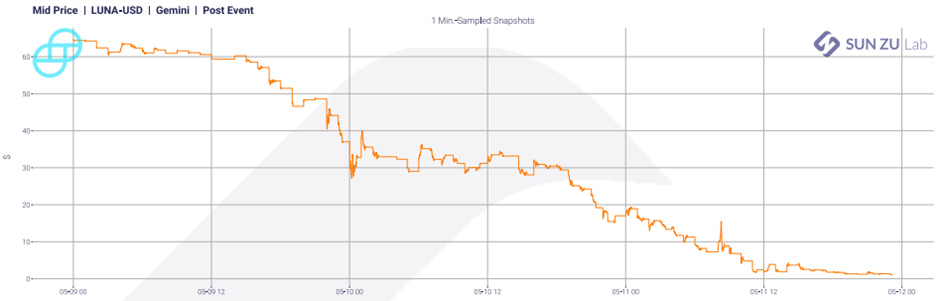

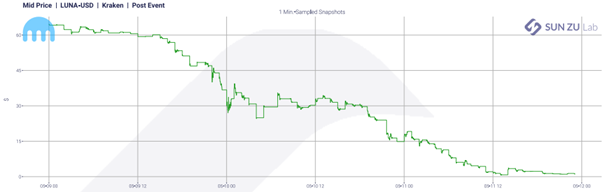

After May 9th, this “rebound” behavior disappears entirely, markets just “give-up” for LUNA, and UST trades at levels much lower than its peg value:

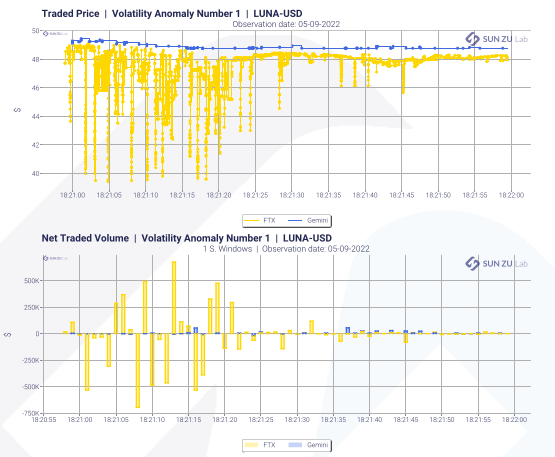

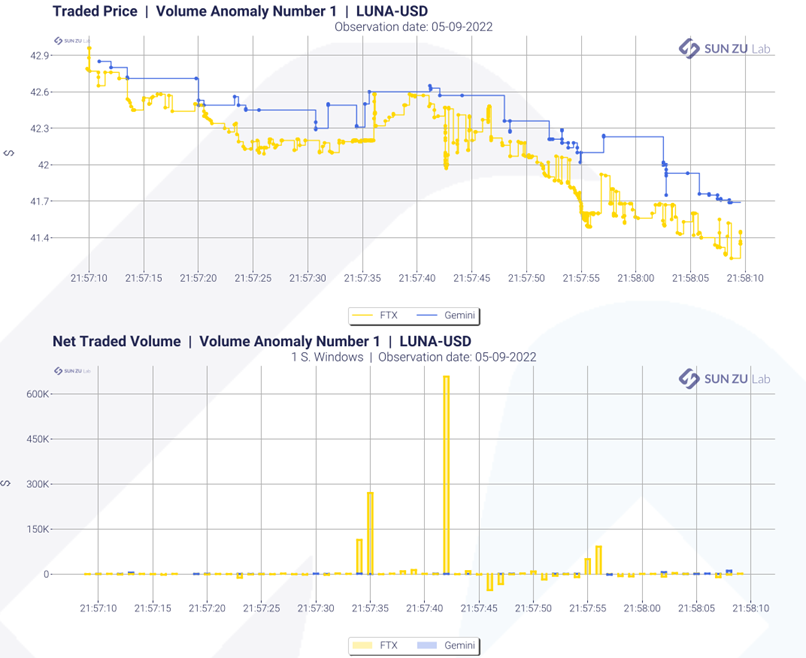

When zooming closer at periods where activity is very surprising (to the point where our filters identify them as “anomalies”), here is one example of what we find on May 9th:

The biggest orders were sent in the middle of the crash. At 19:07 and 21:57:

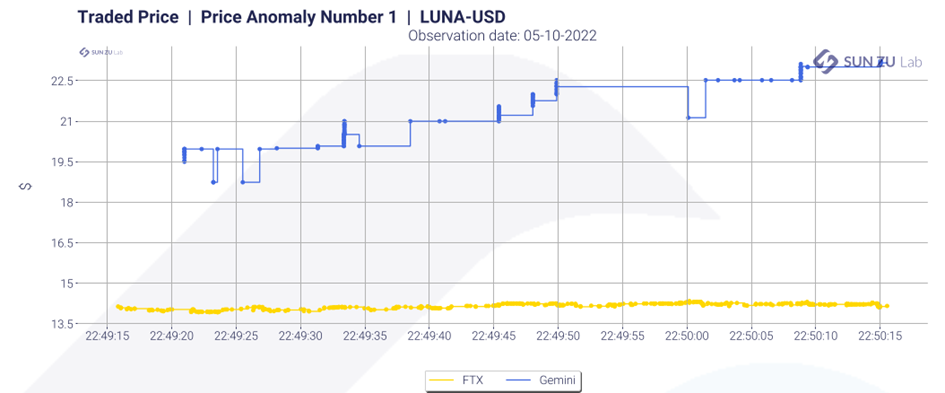

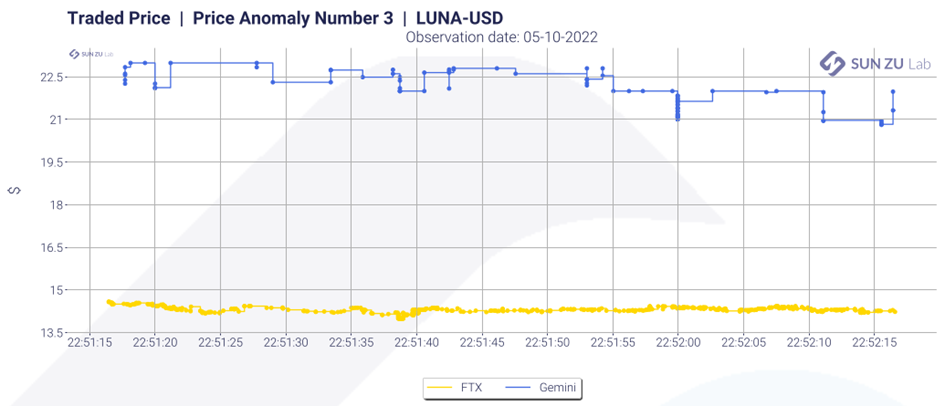

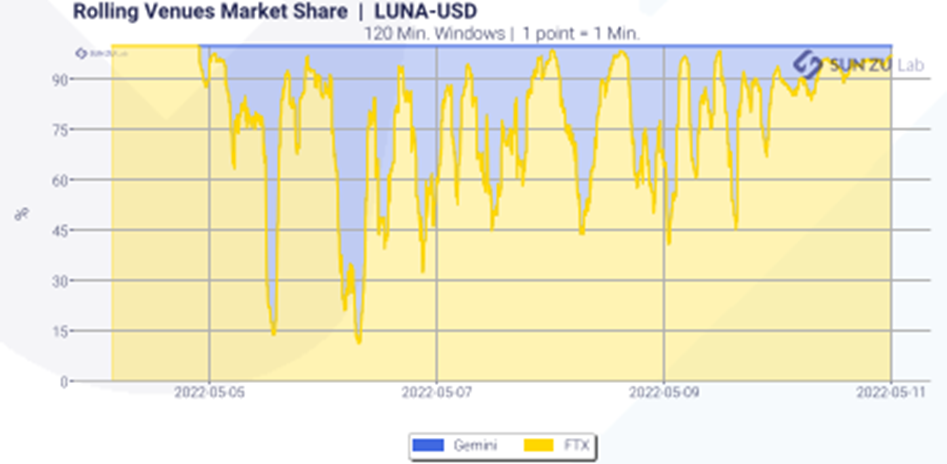

Following the crash, we observe a strong desynchronization between prices on FTX and Gemini, as can be seen below, where prices differed by more than $8 for several minutes. In addition, Gemini suffered a dramatic 9-fold decrease in market share on the LUNA-USD pair:

At the beginning of the crash, Gemini had a book twice as full as that of FTX, which can explain the large trades and other strange events observed on FTX. Logically, it was easier for manipulators to move the price on the market where the book was the thinnest. Following the crash however, the liquidity available in Gemini’s order book was almost non-existent.

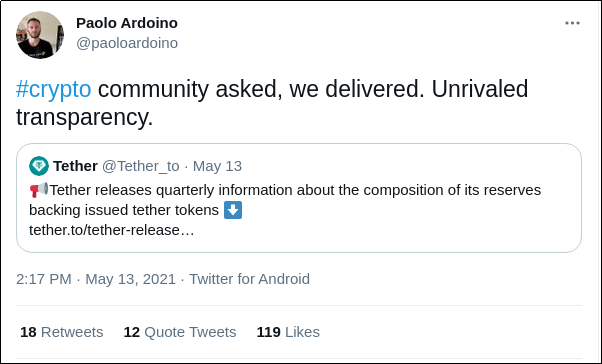

Tether ($USDT), the crypto market’s largest stablecoin, also displayed symptoms of stress as Terra’s UST stablecoin imploded. It abruptly lost its $1 USD peg in early morning trading, falling as low as $0.95 before going back to $1.

Aftermath

On May 13th, block production on Terra was temporarily paused to prevent second-order consequences on network stability and governance caused by hyperinflating supply. Trading of $LUNA pairs was also suspended on some exchanges like Binance and Coinbase as it traded at less than a tick’s value.

In an effort to preserve the community and the developer ecosystem, Do Kwon (CEO of Terraform Labs, the company behind Terra) came up with the Terra Ecosystem Revival Plan. In order to significantly strengthen the liquidity around $UST peg, the LFG Council voted to loan $750M worth of $BTC to trading firms to help protect the $UST peg, and to loan $750M UST to accumulate $BTC as market conditions normalized. In addition, the foundation is looking to use its remaining assets to compensate current and past holders of $UST.

Distribution of LFG’s Reserve Assets as of 16 May 2022

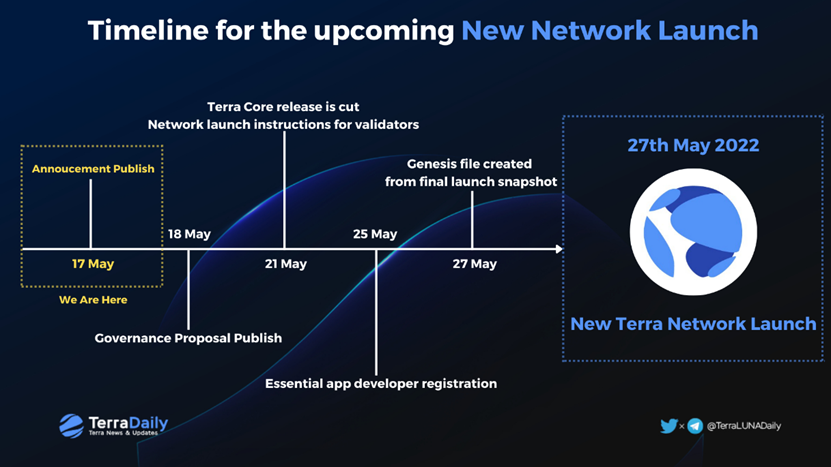

On the 16th of May, Do Kwon published the Terra Ecosystem Revival Plan 2, where he imagines a fork in the Terra chain that will lead to a new chain without the algorithmic stablecoin. While the entire crypto-currency market has mixed opinions on this new experiment, it is clear once again that more scrutiny is needed to protect the small holder and protect the market from counterparty risk.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading independent provider of liquidity analysis for investors already active or crypto-curious. We provide quantitative research on the liquidity of all digital assets to help investors improve their execution strategies and source the highest level of liquidity at the lowest cost.

Our product line includes research reports, software tools, and bespoke developments to fulfil the needs of the most demanding digital investor.

Liquidity Primer: an overview of Liquidity in Crypto Markets

By Chadi El Adnani, Crypto Research Analyst @SUN ZU Lab

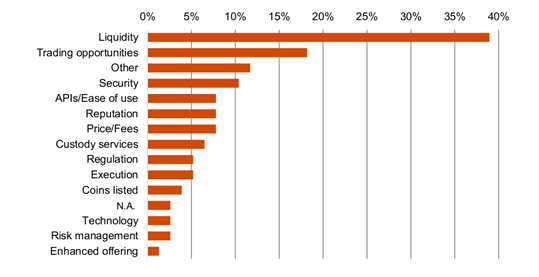

All seasoned investors know this for a fact: the first and foremost characteristic of a financial instrument is its liquidity. In its 4 th annual global crypto hedge fund report published recently, PWC confirmed that liquidity is indeed the most common consideration for crypto funds when choosing a trading venue (cited by 39% of respondents, see below). This percentage is significant and far above the next consideration, trading opportunities, at 18%. In the wake of this finding, we felt an overview of market liquidity with a focus on crypto markets was a good idea. Too often is the concept of liquidity overlooked or taken for granted, whereas in real life it is not only critical but difficult to quantify or elicit. In this article we provide general foundations about what liquidity is, its variations and manifestations

What are the most common considerations for crypto funds when choosing a trading venue?

Source: PWC 4 th annual global crypto hedge fund report 2022

What is liquidity ?

We focus in this article on market liquidity, which is a different concept from monetary liquidity: a company’s ability to meet its current liability commitments. Liquidity is defined as the ability to buy or sell large quantities of an asset without significant adverse price movement. It is an important factor that investors need to assess before executing their trades, since it is a clear constraint on how quickly they can gain access to the market and subsequently how fast they can lock in a profit from a particular asset.

There exists different types of market liquidity:

We identify at SUN ZU Lab three different types of market liquidity: transaction liquidity (post-trade), order book liquidity (pre-trade) and invisible liquidity. Those notions are additive, in the sense that all three exist at the same time for a given instrument. Yet there is a timing dependency between them: invisible liquidity needs to become visible (pre-trade) before it can be consumed (post-trade).

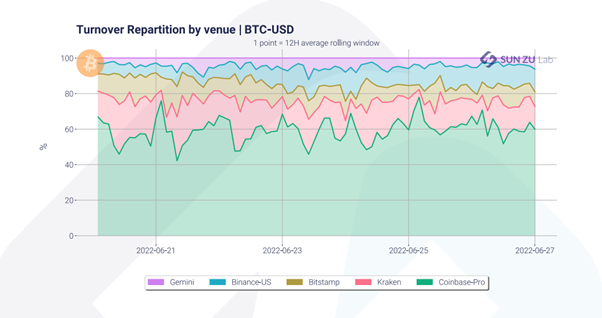

Derivatives markets, whether in crypto or TradFi, enjoy far more liquidity than spot markets. The Bitcoin futures market, for example, saw average monthly turnover of $2 trillion at its peak, a far greater figure than BTC spot markets’ volumes. Liquidity is not only variable in time, it is also distributed in space across multiple venues. Our data shows for example that BTC trading volumes are fragmented across exchanges, as seen in the graph below (limited to 5 exchanges, and in reality there are many more creating an even higher degree of fragmentation).

Source: SUN ZU Lab data

Transaction liquidity:

Transaction liquidity refers to liquidity that has been expressed through actual trading volumes. This is an important indicator as high trading volumes usually imply less difficulty to buy or sell large quantities. Among the most liquid markets we can cite the forex market, thought to be the most liquid in the world as major currency pairs are traded by governments, banks, and even individuals. The stocks and commodities markets are very liquid as well, although intuitively no large cap or bond will ever be as liquid as a national currency.

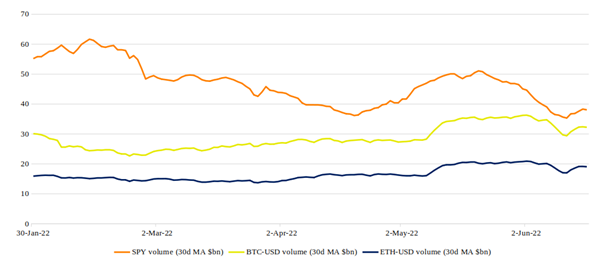

Source: data from Yahoo Finance

In the graph above, we show daily trading volumes in 2022 for the S&P 500’s most liquid ETF, Spider SPY, as well as BTC-USD and ETH-USD. The S&P 500 ETF is one of the most liquid instruments in the world, with $30 to $60 billion traded every day. Data shows that Bitcoin and Ether’s daily trading volumes vary in range between $10 and $40 billion.

These figures however need to be taken with a grain of salt due to various sources reporting that officially announced crypto trading volumes are greatly overestimated with the magnitude of fake volumes varying over time.

Order book liquidity (pre-trade):

Order book liquidity represents the total nominal (price * quantity) visibly offered across all available trading venues. This liquidity materialises as different buy/sell quantities sent by investors at different prices. Across all buy orders, the best price is referred to as “best bid”, and the “best offer” on the other side across selling orders. The mid price is quite logically the middle of those two.

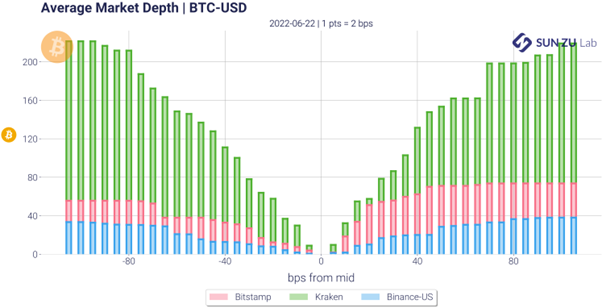

A visible order book represents the underlying supply and demand of an asset in the form of individual bid and ask orders. To illustrate this, here is a chart compiled by SUN ZU Lab showing how average liquidity aggregates around mid-price for BTC-USD on three main exchanges: Bitstamp, Kraken and Binance-US on the 22 nd of June, 2022.

Source: SUN ZU Lab data

The chart reads as follows: each bar represents the average quantity of BTC (in number of BTC) offered for buy/sell orders. For example, there were on average 200 BTC offered for sale at 80bps from mid-price on the three exchanges against around 210 BTC bid offers at -80bps from the mid-price.

Order books communicate information about investors expectations and appetite. In particular there appears a new concept to qualify liquidity: the bid-ask spread, which is the difference between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay for an asset and the lowest price a seller is willing to accept. The magnitude of this spread gives a good indication about an asset’s liquidity. For example a large spread indicate poor offer and/or demand, and incidentally may drive the volatility higher. Conversely a narrow spread is an indication of a deeper market where investor’s interest is high, and volume potentially abundant for buyers and sellers to execute their trades. Bid-ask spreads for Bitcoin, for example, used to be higher than 10% in the early days of crypto, but they have dropped massively to as low as 10bps on the main exchanges as crypto adoption, investor interest and trading volumes increased over time.

Invisible liquidity:

We refer to invisible liquidity as all forms of liquidity that is not captured in public trades or order books. Note for example that liquidity exposed to a limited set of investors would qualify here as invisible liquidity (more on this below).

In general terms, the taxonomy of “invisible liquidity” is extremely difficult to establish as it depends on the structure of the market. In markets where OTC activity is high, those trades and the interaction of brokers with their client are compartments of invisible liquidity.

One could argue that those compartments divert liquidity away from other pools, yet not all investors have access to it. In markets where OTC is not developed, those liquidity pools simply do not exist.

In the world of crypto, we distinguish the following categories:

● Non-communicated, invisible orders: quantities available for trading that are yet to be communicated by investors to the markets. There is virtually no way to quantify these volumes as they only exist in a theoretical state in strategy books of portfolio managers.

● Communicated, invisible orders: we put in this category for example trading activity of dark pools, also known as Alternative Trading Systems (ATS). These are private marketplaces where investors place buy and sell orders, without the venue disclosing available prices or volumes. Liquidity has found its way to the marketplace, it is just not visible (by anybody).

● Communicated, partially-visible orders: quantities available for purchase or sale, expressed through an Indication of Interest (IOI), which refers to an investor’s non-binding interest in a security, usually communicated to a broker. In traditional markets, IOI are heavily regulated because, depending on applicable rules, they constitute visible or invisible liquidity. The regulators’ particular interest on this

compartment stems from the fact that liquidity visible only by a few agents is easily manipulable.

● DeFi liquidity: this is liquidity placed on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) without being incorporated into order books. We will dive more in detail into how liquidity pools in DEXs work in another article.

● On-Chain Liquidity: centralized exchanges (CEXs) rely on the “order book” mechanism to enable off-chain transactions: aggregate positions are “written” on chain only when investors transfer their positions out of exchanges (and de facto reclaim ownership of those on their wallets). Pure on-chain transactions today account for a relatively small percentage of total volumes. Decentralized exchanges (DEXs) are another form of on-chain liquidity, that relies on smart contracts to execute trades automatically, recorded directly (and immediately) on blockchains.

Data from Chainalysis shows that DEXs have surpassed CEXs in terms of on-chain transaction volume in January 2021, with a $175 billion volume sent on-chain to CEXs from April 2021 to April 2022, vs. a $224 billion volume sent to DEXs during the same period.

● Peer-to-Peer Liquidity: P2P is a type of crypto exchange trading that allows traders to trade directly with one another without the need for a centralized third party to facilitate the transactions. This method allows exchanging parties to select a preferred offer and trade directly without using an automated engine to execute transactions.

Liquidity risks

The main liquidity risk associated to markets is for investors not to be able to enter/exit their positions due to a lack of sellers/buyers offering a fair price. One of the markets where this type of risk is the most visible is the real estate market. During times of economic turmoil or bad real estate market conditions, it could become impossible to find a buyer at the right price even though the property may have obvious value. A perfect example for this is the experience of NBA superstar Michael Jordan in trying to sell his Chicago mansion that has been on the market for 10 years already! The over-equipped luxurious house was originally listed for $29 million, before the owner was obliged to cut the price nearly in half overtime to try and match market expectations.

There is also another psychological effect that comes into play with illiquidity; the longer an asset is listed for sale, the more potential buyers are keen to second-guess their decision as the lack of interest and competition over the asset drives its value lower.

All of this has been extensively studied in traditional finance, and has become known as the “liquidity premium”: there is a clear relationship between price and liquidity. The higher the liquidity, the higher the price. This is the reason why real-estate prices are often subject to discount when economic conditions are under stress. We provide links to research articles about this subject in the appendix.

Conclusion

Liquidity is one of the most important concepts for individuals, institutional investors as well as exchanges and market makers. Despite holding high-value assets, any of these entities may experience a liquidity crunch if such assets cannot be sold within a short period. This is turn create heavy pressure on prices.

Top crypto projects’ tokens such as BTC, ETH, BNB or SOL appear to have reached a reasonable level of liquidity, but this is not the case for the vast majority of tokens that are only listed on one or two exchanges, with very low daily trading volumes and market depths. Above all, liquidity of the entire crypto market is still nowhere near liquidity levels visible in traditional markets.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com

Appendix:

- Chainalysis June 2022 report

- “Liquidity and Asset Prices” by Amihud, Mendelson and Pedersen

- “The relationship between stock price and liquidity” by Murphy Lee

- “Measuring Liquidity Premiums for Illiquid Assets” by Anson

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading independent provider of liquidity analysis for investors already active or crypto-curious. We provide quantitative research on the liquidity of all digital assets to help investors improve their execution strategies and source the highest level of liquidity at the lowest cost.

Our product line includes research reports, software tools, and bespoke developments to fulfil the needs of the most demanding digital investor.

Transaction Cost Analysis: the answer to all hidden costs behind crypto trading (1/2)

By Chadi El Adnani, Crypto Research Analyst @SUN ZU Lab

The “odd-eighth quotes” phenomenon

To introduce this article about Transaction Cost Analysis, we first revisit a very famous historical case. Before decimalization, the US stock market tick size used to vary by increments of 12.5 cents. This means that all prices were quoted in eighths of a dollar (ex. $12 or $12 1/8). However, on May 26 and 27, 1994, several US national newspapers reported an article that first appeared in the Journal of Finance (“Why Do NASDAQ Market Makers Avoid Odd-Eighth Quotes?”, by Christie, Harris and Schultz) raising the question of the width of the range of prices quoted by NASDAQ market makers. The researchers had found that the prices quoted to investors were almost systematically 1/4 ($0.25) apart, thus avoiding the minimum allowable 1/8 spread ($0.125)

To get a first grasp of the implications of this situation, we need to highlight that the range quoted by market makers is a good indication of the maximal margin they intend to capture. So by quoting a stock at $12 – $12 1/4 (i.e. they are willing to buy at $12 and sell at $12.25), instead of the allowed $12 1/8 – $12 1/4 range, market makers are refusing to decrease their margin bellow $0.25. So what would prevent market makers from avoiding odd-eighth quotes on 70 out of 100 actively traded NASDAQ securities, including Apple Computer and Lotus Development? The authors found no explanation and concluded that the situation was probably the result of implicit collusion among the participants to maintain wide spreads.

Surprisingly, On May 27, dealers in Amgen, Cisco Systems, and Microsoft sharply increased their use of odd-eighth quotes leading effective spreads to fall “magically” by nearly 50%, this pattern was repeated for Apple Computer the following trading day. Noticing these weird trends, the same authors published a new article a few months later to reconduct their investigation (“Why did NASDAQ Market Makers Stop Avoiding Odd-Eighth Quote?”). Using individual dealer quotes for Apple and Microsoft, the authors found that virtually all dealers moved in unison to adopt odd-eighth quotes.

These strange findings led thousands of individual investors to file a class-action lawsuit against 30 brokerage firms, including Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which agreed in 1997 to pay about $900 million in what was called at the time the biggest settlement ever of a price-fixing lawsuit.

What is Transaction Cost Analysis?

What the researchers behind the article have provided is part of what is known nowadays as Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA). Transaction costs have become a relevant issue in Europe for example since 2007 with the implementation of MiFID (Markets in Financial Instruments Directive). The introduction of the best execution obligation gave TCA a central role, aiming for investment firms to “take all reasonable steps to obtain the best possible result when executing orders for their clients”. Moreover, MiFID’s Article 21 of Level 1 and Article 45 of Level 2 require investment firms to provide their clients with “appropriate information” about their execution policies. Clients wishing to select a firm to deal with from among a competing group need to have sight of the relevant firms’ execution policies in order to evaluate whether a particular investment strategy is suitable. By requiring ex-ante disclosure of the execution policy, MiFID addresses clients’ information needs; they should always be able to pay the lowest possible net cost (or receive the highest possible net proceeds).

Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA) is the study of trade prices to determine whether trades are arranged at favourable prices (low prices for purchases and high prices for sales). The difference between the cost of the transaction at the time the manager decided to execute it and the actual cost is at the heart of TCA, including all operating charges, spreads, commissions and fees. The resulting differential is called “slippage”.

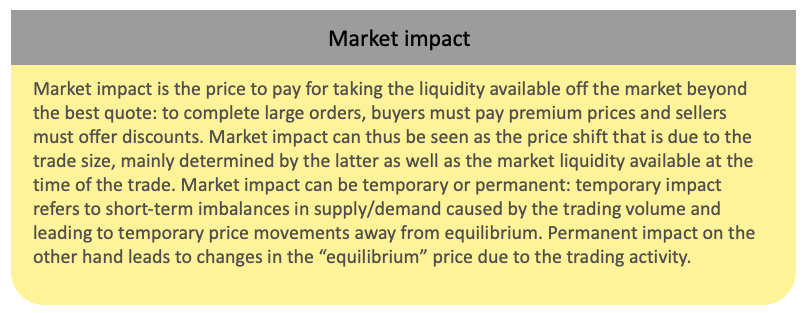

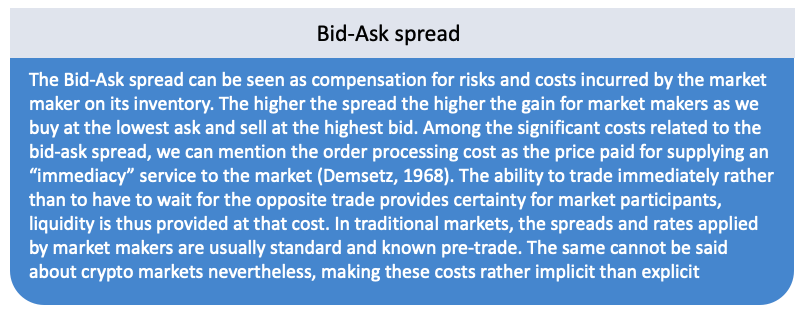

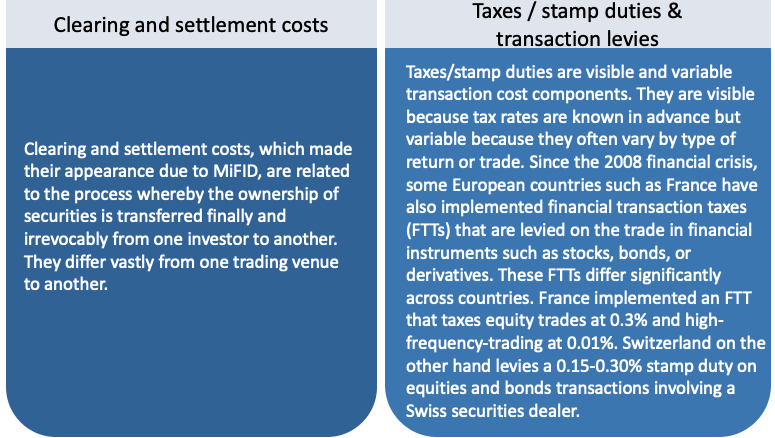

There are usually 9 components identifiable when dealing with transaction costs, they can be classified as per the following chart:

Implicit transaction costs:

Market Impact and various Opportunity costs detailed as follows:

Explicit transaction costs:

Brokerage Commisions, Market fees, Clearing and Settlements costs, Missed Trade opportunity costs, Bid-Ask spread detailed as follows:

Conclusion

The same transaction costs exist for crypto trading as well but suffer from a severe lack of transparency. The Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) regulation in its latest version comes however with a “best execution” obligation that should force digital assets service providers down the same path as their TradFi peers. This obligation should come with extensive quantitative analytics of order execution prices, leading to increased competition among trading venues and liquidity providers. When that day comes, institutional and retail crypto investors should be able to rely on Sun Zu Lab’s advanced and completely independent liquidity analytics to provide much-needed transparency to the crypto ecosystem.

In the next part of this article to be published, we will look at pre and post-trade TCA and analyse how this process actually works and how it helps an investment manager save money.

Questions about this article can be addressed to research@sunzulab.com or c.eladnani@sunzulab.com

Sources:

- “Why do Nasdaq Market Makers Avoid Odd-Eighth Quotes?” by William G. Christie and Paul H. Schultz, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2329272

- “Why did Nasdaq Market Makers Stop Avoiding Odd-Eighth Quotes?” by William G. Christie, Jeffrey H. Harris and Paul H. Schultz, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2329273#:~:text=On%20Thursday%20May%2026%2C%20the,quotes%20for%20active%20NASDAQ%20stocks.

- 30 Firms to Pay $900 Million In Investor Suit: https://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/25/business/30-firms-to-pay-900-million-in-investor-suit.html

- EDHEC research publication, https://risk.edhec.edu/sites/risk/files/EDHEC_Publication_Transaction_Cost_Analysis_A-Z.pdf

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a French Fintech that aims to become the leading independent provider of digital asset market quantitative analytics tools and services. Leveraging the founding team’s 70+ years of experience in international capital markets and trading technology, SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with unprecedented liquidity analytics in the form of quant reports, dashboards, real-time augmented data feeds, and bespoke studies.

What is Tokenomics and why does it matter?

A brief historical perspective to better understand the stakes behind tokenomics

Let’s start this article with the famous experience of Philip II, King of Spain in the 16th century, with the Eldorado discovery and the massive rise in inflation that followed throughout the entirety of Europe!

In the 16th century, Spain conquered Latin America and discovered an immeasurable wealth within gold and silver mines. The kingdom hit the jackpot, and its financial deficits appeared long behind it. Nevertheless, this wasn’t the case; the problem came from the Crown of Spain being over-indebted to many European creditors, leading the massive silver and gold discoveries to only make a quick passage through Spain before enriching the coffers of its French and Dutch neighbors. The European market ended up flooded with coins, so the immense Spanish wealth was diminished relative to other European kingdoms.

In the end, the excessive amount of silver and gold imported, and above all distributed, in Europe caused a substantial devaluation of what Philip II could think of as his Eldorado. A better financial management could have allowed him to preserve his reserves of invaluable minerals and thus be able to develop on a more critical scale of time his fabulous treasure.

This story shows the importance of the quantity put into circulation on the valuation of an asset. This analysis works perfectly for the cryptocurrency market as well; any analysis of an asset’s ecosystem requires careful attention to the notions of quantity in circulation, total quantity, and inflation management.

Inflation and the importance of tokenomics

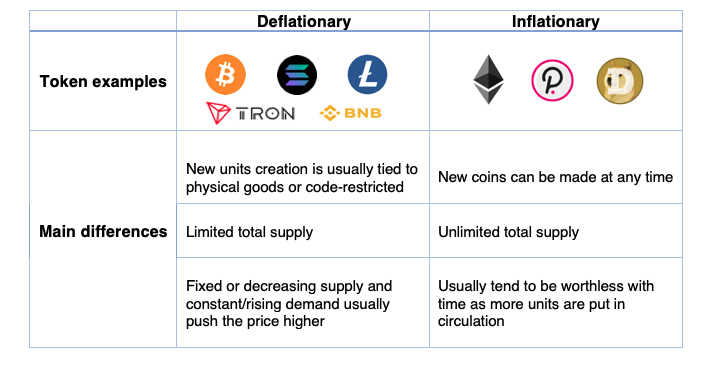

While the media usually describes inflation as a rise in the price of everyday consumer goods, it is, in reality, the value of money that tends to fall rather than prices getting higher. This notion of inflation is at the heart of tokenomics, a merger of “token” and “economics” used to refer to all the elements that make a particular cryptocurrency valuable and exciting to investors. In this regard, two predominant models exist: deflationary and inflationary tokens.

- The limited quantity deflationary model:

This is the model Bitcoin uses, i.e. a fixed total supply and less and less money issued over time. Many cryptocurrencies are governed under this model, like Solana, Litecoin, Tron, and many others, alongside the king of cryptos.

In the case of Bitcoin, for example, a block is mined about every 10 minutes, rewarding the miner 6.25 BTC (when Bitcoin started, it was 50 BTC per block, then 25, 12.5, 6.25, etc). The reward is halved every 210K blocks, leading to a halving every 4 years with the 10 minutes mining-time per block assumption. Without changes to the protocol, the final Bitcoin will be mined around the year 2140.

- The balanced inflation model:

Many blockchains have been coded without incorporating a limited amount of token issuance. This choice can be made for a variety of reasons, usually involving the use to be made of the blockchain in question. The Ethereum protocol, for example, operates under this model. However, some mechanisms are put in place to limit inflation or even to create a deflationary system.

This is the objective of implementing future updates of the Ethereum network. While the annual rate of ETH token issuance is currently equal to nearly 4.5%, the switch from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake should allow developers to reduce this rate to less than 1%. The network also introduced a burn mechanism, meaning that part of the fees paid by Ethereum users in the future will not be returned to validators, but will be removed altogether. This could not only achieve a balance with the issuance rate, but potentially lead to a decrease in the number of tokens in circulation in case of high network usage.

Both models have strengths and weaknesses, with reasonable justifications behind their use. For example, the Ethereum white paper indicates that a stable issuance rate would prevent the excessive concentration of wealth in the hands of a few actors/validators. Whereas Bitcoin’s deflationary system, as previously stated, allowed for the growing development of its ecosystem by paying miners large amounts of Bitcoin when it was not worth the tens of thousands of dollars it is worth today.

More generally, looking into a project’s tokenomics before getting involved is always a good idea. This can help answer questions like:

- What is the current token supply as well as total supply?

- Does the token have an inflationary or deflationary model?

- What is the real-world use case?

- Who owns the majority of coins? Is it well spread out or concentrated?

Main differences between deflationary and inflationary tokens:

Solana case study

Let’s take a deep dive into one of the most prominent blockchains’ tokenomics. Solana has a native token called SOL that has two primary use cases within the network:

- Staking: users can stake their SOL either directly on the network or delegate their holding to an active validator to help secure the network. In return, stakers will receive inflation rewards.

- Transaction Fees: users can use SOL to pay fees related to transaction processing or running smart contracts.

The Solana team distributed tokens in five different funding rounds, four of which were private sales. These private sales began in Q1 2019 and culminated in a $20 million Series A led by Multicoin Capital, announced in July 2019. Additional participants included Distributed Global, BlockTower Capital, Foundation Capital, Blockchange VC, Slow Ventures, NEO Global Capital, Passport Capital, and Rockaway Ventures. The firms received SOL tokens in exchange for their investments, although the number of tokens allocated to investors was not disclosed.

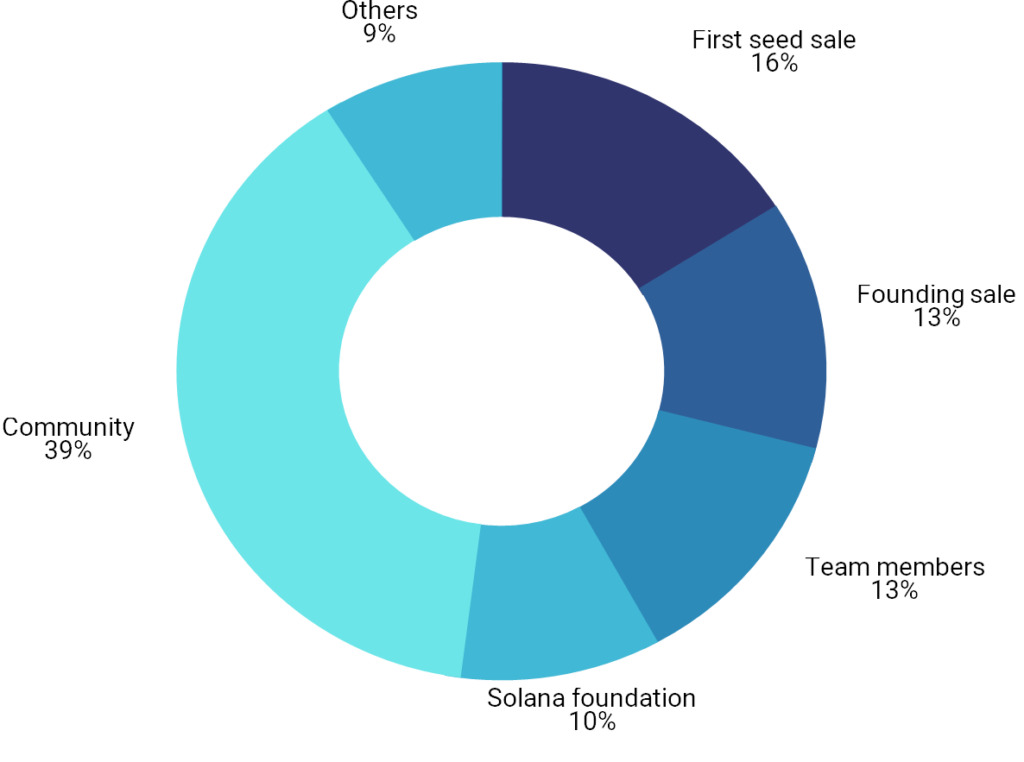

The initial distribution of SOL tokens was as follows:

According to Messari data, vesting schedules were as follows: Solana’s three pre-launch private sales all came with a nine-month lockup after the network launched. The project’s public auction sale (held in March 2020) did not come with a lockup schedule, and the SOL tokens distributed in that sale were fully liquid once the network launched. The founder’s allocation (13% of the initial supply) was also subject to a nine-month lockup post-network launch. After the lockup period ends, these tokens will vest monthly for another two years (expected to fully vest by January 2023). This last clause is a good protection for investors as team members’ tokens are locked-up for a longer period. The Grant Pool and Community Reserve (both overseen by the Solana Foundation) contain ~39% of the initial SOL supply combined. These allocations began to vest in small amounts since Solana’s mainnet launch.

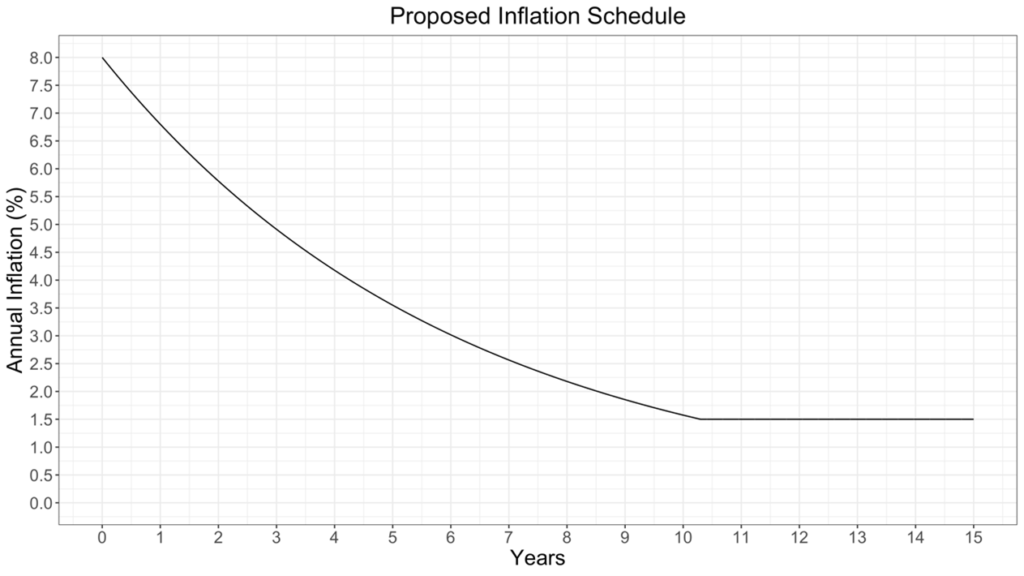

Inflation stands at an initial annual inflation rate of 8%. However, this inflation rate will decrease at an annual rate of 15% (“dis-inflation rate”). The inflation decrease is thus non-linear and much more important in the first years. Solana’s inflation rate will continue to decrease until it reaches an annual rate of 1.5%, which the network should reach in about ten years or 2031. 1.5% will remain the long-term inflation rate for Solana unless the network’s governance system votes to change it.

Major identified issues with current projects’ tokenomics

- Is it really that decentralised?