This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Our take on the liquidity of digital assets

A more systematic approach to liquidity monitoring

We at SUN ZU Lab have a deep curiosity about digital assets. Like everyone else, we follow bitcoin’s saga, with a volatility which, after all, is probably regarded more as a source or opportunity than a risk to be curtailed.

As we have written before (here and here), if digital assets were to constitute only a new source of liquidity, they would be an invaluable development in modern finance. Whoever has spent time on capital markets knows that liquidity is an elusive target at best. After decades of electronic trading, intense innovation, and regulatory adjustments, attracting and retaining liquidity remains as difficult as ever. Exchanges and trading venues worldwide know it firsthand, their primary responsibility is indeed to attract liquidity, one way or the other. Many have adopted “market-making” schemes whereby they basically waive fees and sometimes actually pay for participants to contribute orders in their central order book.

Liquidity is defined as the ability to rapidly buy and sell a product for significant size without adverse impact on its price. Note that this definition is not limited to financial products. Real estate for example is a very illiquid asset class. There is a constant trade-off between the time it takes to conclude a transaction and price improvements each party is willing to concede.

Liquidity is a very desirable feature on any developing market, and digital assets are no exception. If the price of bitcoin catches the front news almost every day now, reported trading volumes are also a big part of the story. Taken at face value, those suggest that bitcoin is at least as liquid as some of the most heavily traded traditional instruments (see here and here for a more detailed analysis on the subject).

Even though this is most certainly not true, in great part because volumes are massively manipulated (an x10 factor is commonly hypothesized), the bottom line is that public attention for bitcoin and more generally digital assets is bound to translate into more and more trading activity i.e. more liquidity. In fact, most of it may not even be visible: as investors stand by for the right price to buy or sell, they do not necessarily register their interest with a broker or on the order book of an exchange.

Where is liquidity to be found? There are dozens of venues, on-chain, off-chain, centralized, decentralized. Which venue should you turn to to find the most liquid market? Should you trade on several markets, if so which ones? What price and/or size can you expect if you include 1, 5, 15 markets in your shopping list?

Those are fundamental questions for investors, retail and professional alike. The marketplace is evolving so quickly and in so many different places that it is virtually impossible to follow all relevant developments. That’s where we at SUN ZU Lab, want to help. We started out with a mission: promote a truly institutional standard in the analysis of digital asset liquidity. Our quantitative research is meant to offer a dissected view of liquidity in time and space, so interested parties can get a sense of macro and micro trends to make better-informed decisions for their trading flow.

We had to start somewhere, so we decided to launch our product on BTC, including for the time being 3 markets: Coinbase, Kraken, and Bitstamp. We will be producing 3 reports: one on liquidity, another one will look at market integration (i.e. the existence of price discrepancies between different venues), and the third at what we call market anomalies (i.e. events for which price or volume is an outlier). [Register for our newsletter if you want to hear from us and receive a free sample!]

Let’s look here at the liquidity report. It is a quantitative dissection at liquidity over a 2 week period and will be produced twice a month. Our intention is to present rigorous information to qualify and quantify liquidity dynamics both intraday and over the observed period.

Here is the list of indicators we look at, abstracted from the report over the last 2 weeks in January:

- price and volume-at-price:

This chart is a necessary introduction, we absolutely need to have a sense of how the market has moved over the period, and at what price points have traders concentrated their activity. The volume-at-price add-on on the right side is an elegant way to present this information.

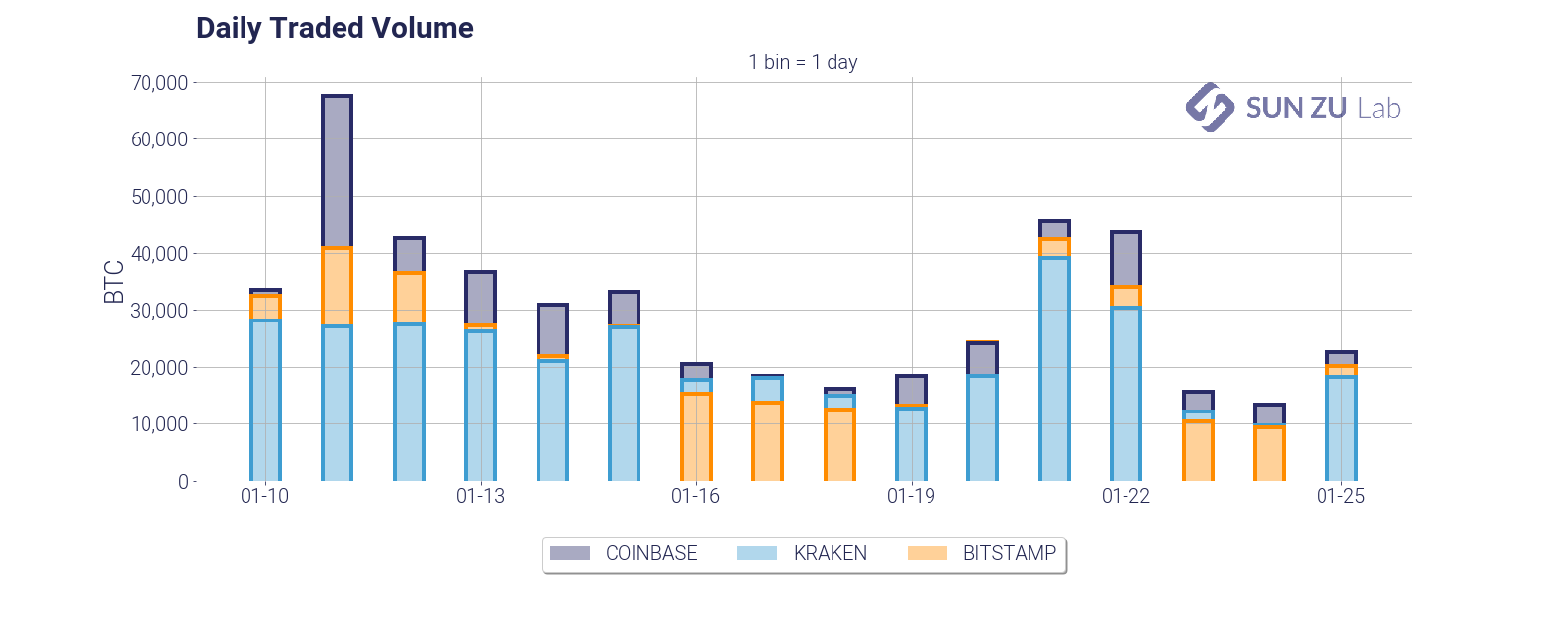

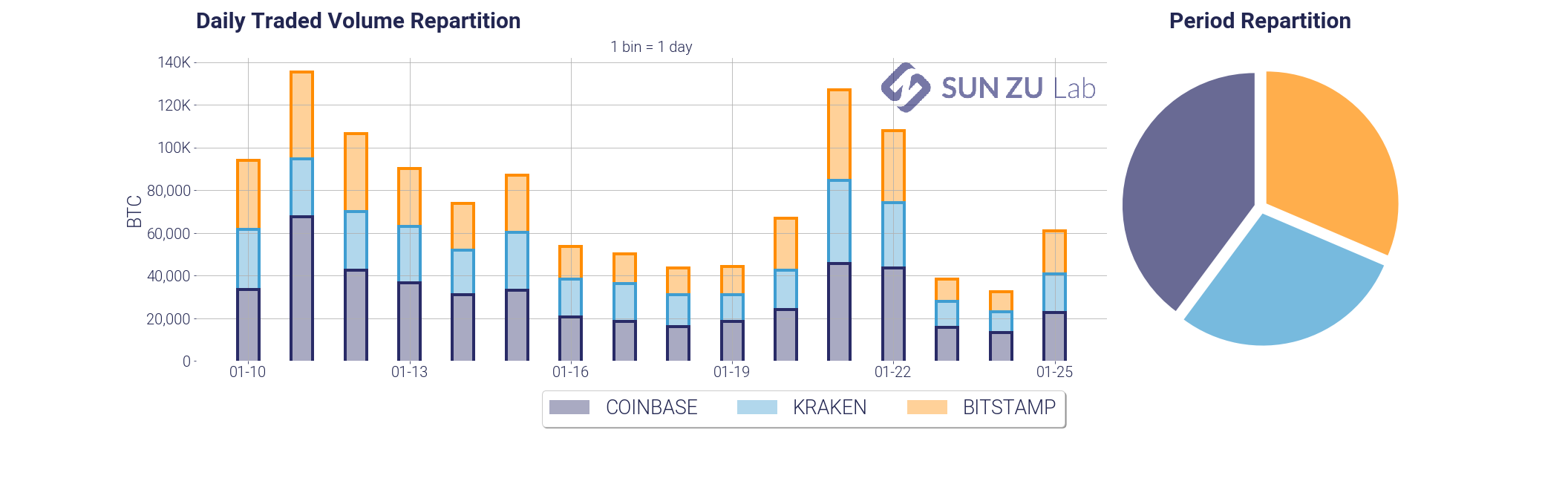

- traded volume, overall and by venue (daily and intraday):

Those two charts are fairly standard representations of volumes. We present both views to determine whether there are intraday patterns that have developed over the observed window. In particular, we could expect higher volumes when Asian and/or US markets open. Quite naturally we need to address also the question of the relative partition between exchanges:

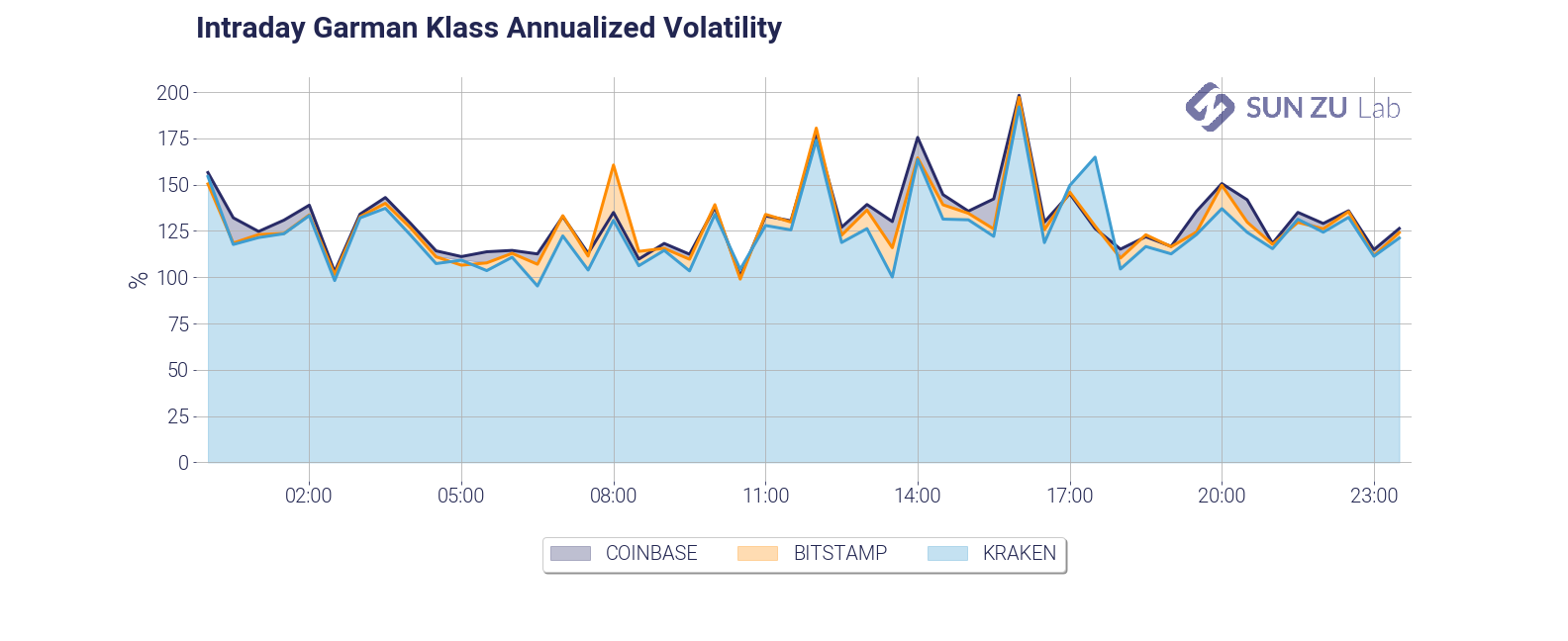

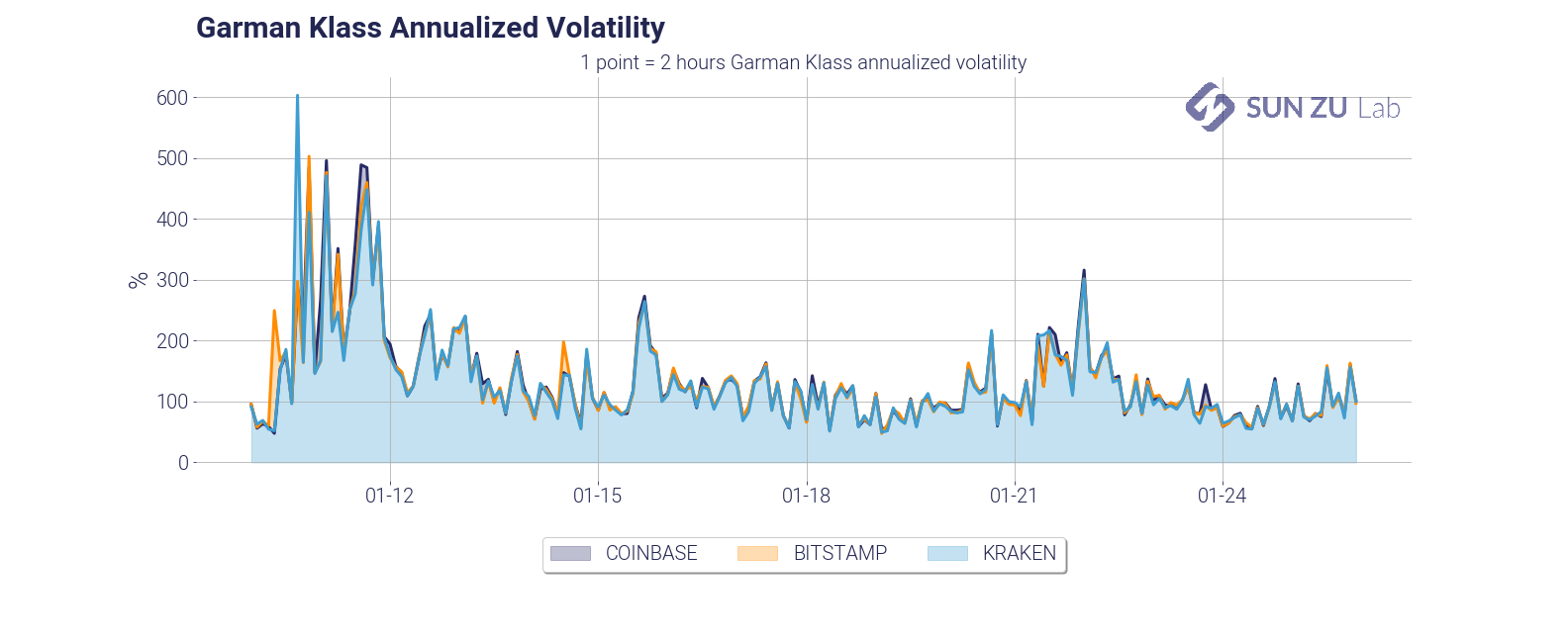

- daily and intraday annualized volatility:

Similarly to volumes, we plot both the intraday and daily volatility to monitor whether intraday patterns developed. Despite the fact that the charts are very similar on distinct venues, we decided to keep them all, to make anomalies between markets stand out, should some come up.

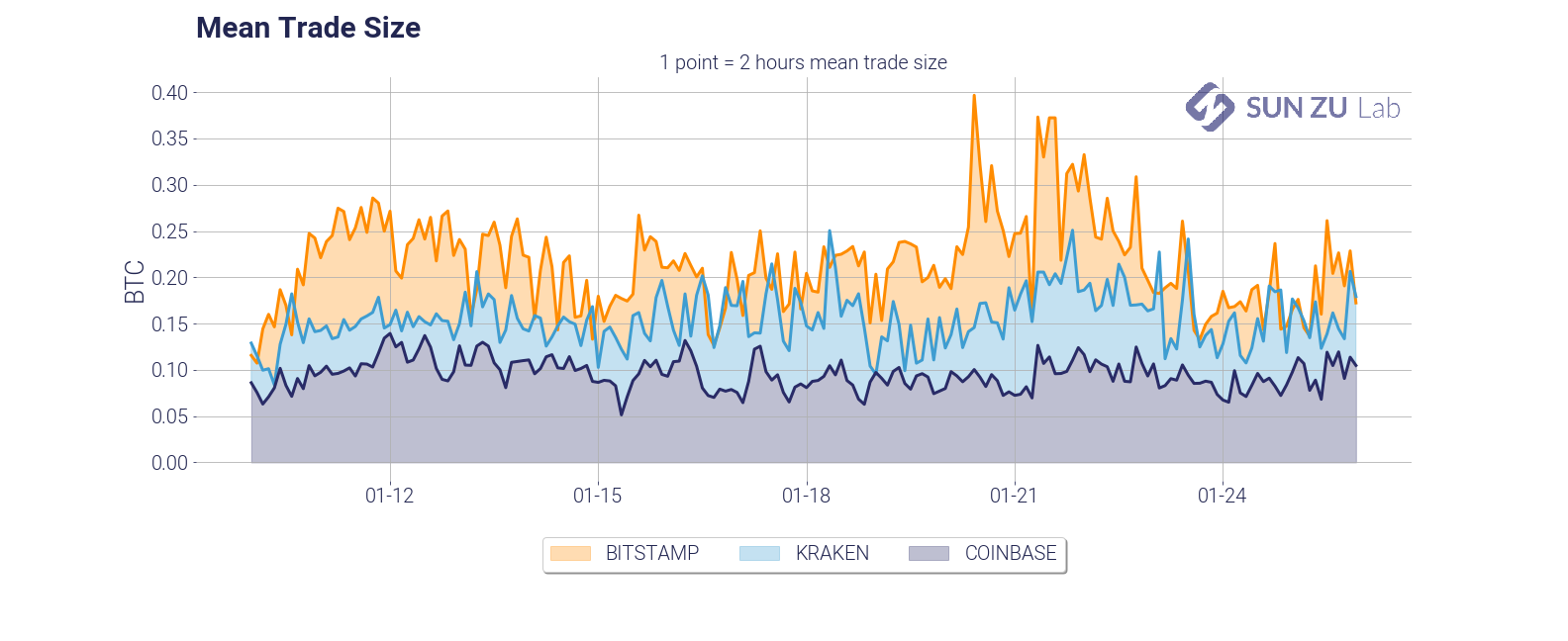

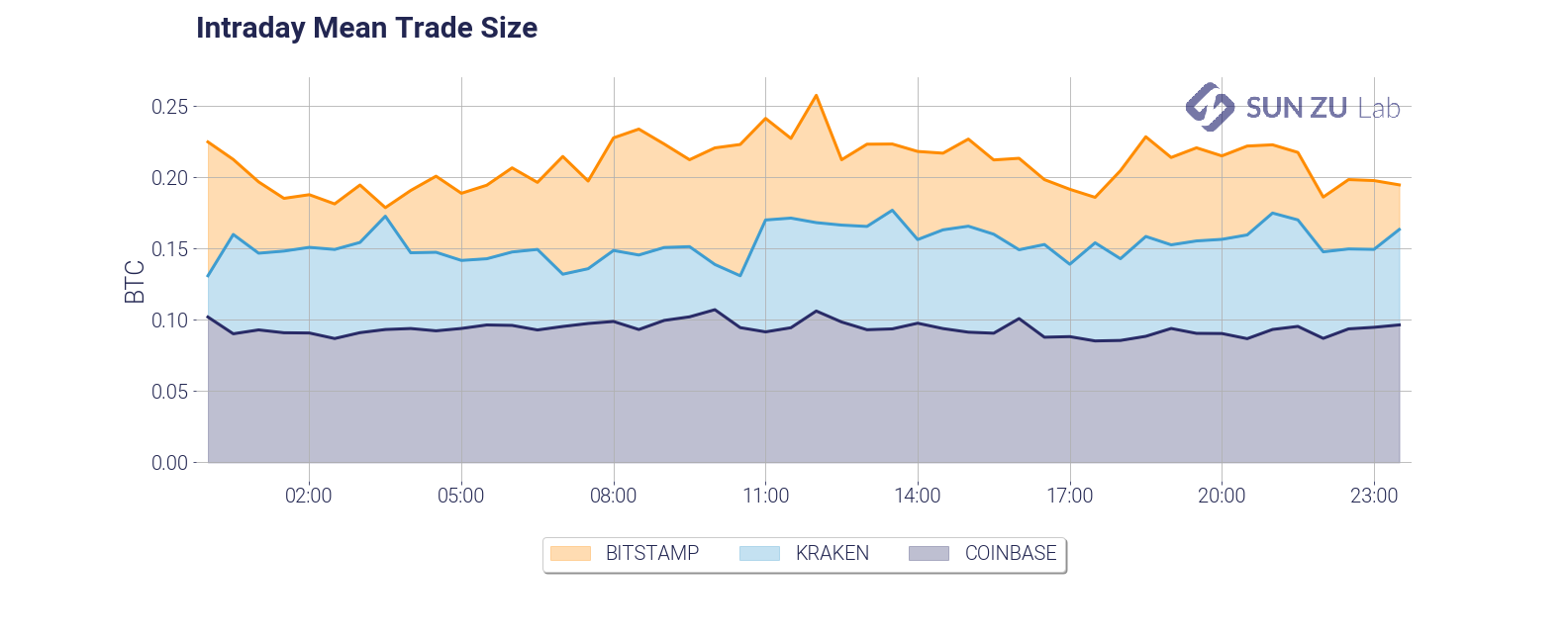

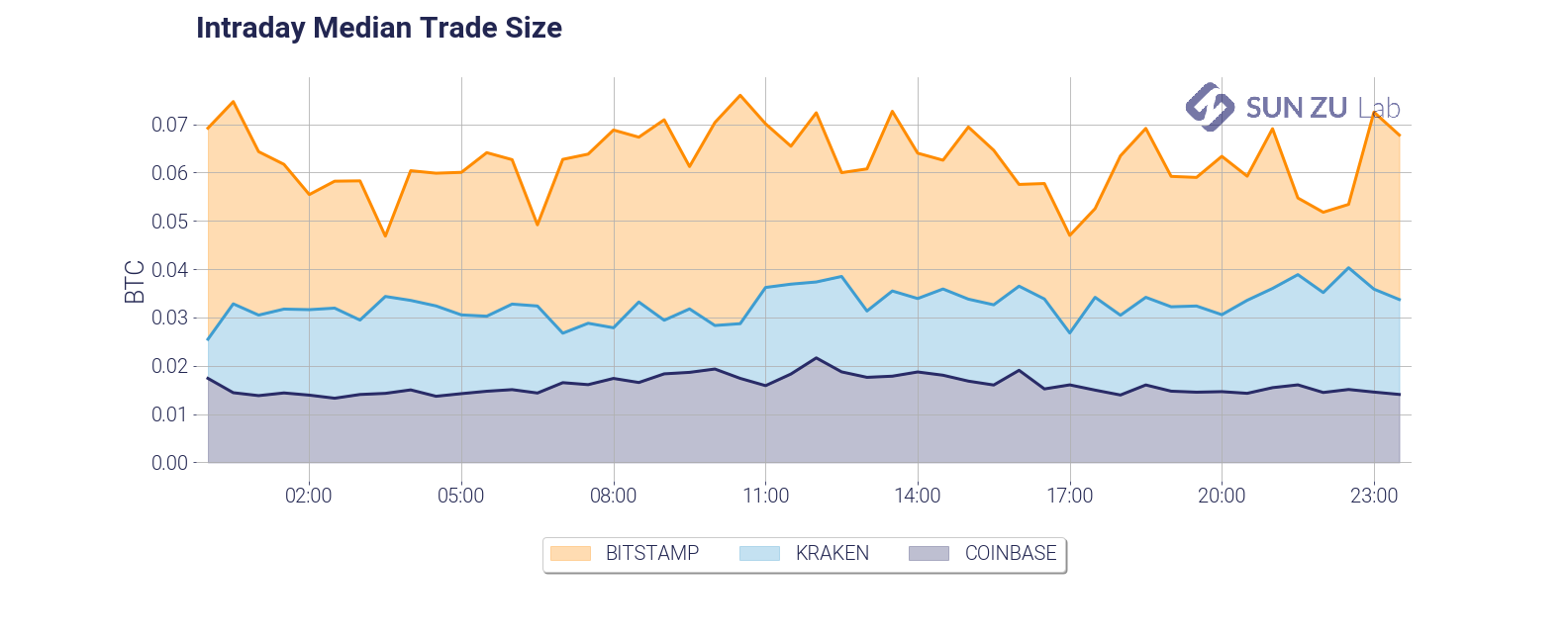

- mean and median trade size (daily and intraday):

The average trade size is a very important feature of liquidity dynamics. It is dependant on a number of factors, such as the type of investors (retail, institutional), the pricing structure of the exchange (fixed vs. variable fees, caps on per-order fees), time of day, etc. We found in our research that infrequent large trades tend to alter the readability of the average, therefore we decided to include the median as well:

Believe it or not, we think there are many more questions that we should be asking. For example: how does trade size vary with volatility? with the bid-ask spread? We will absolutely incorporate the relevant metrics to answer those questions in due course.

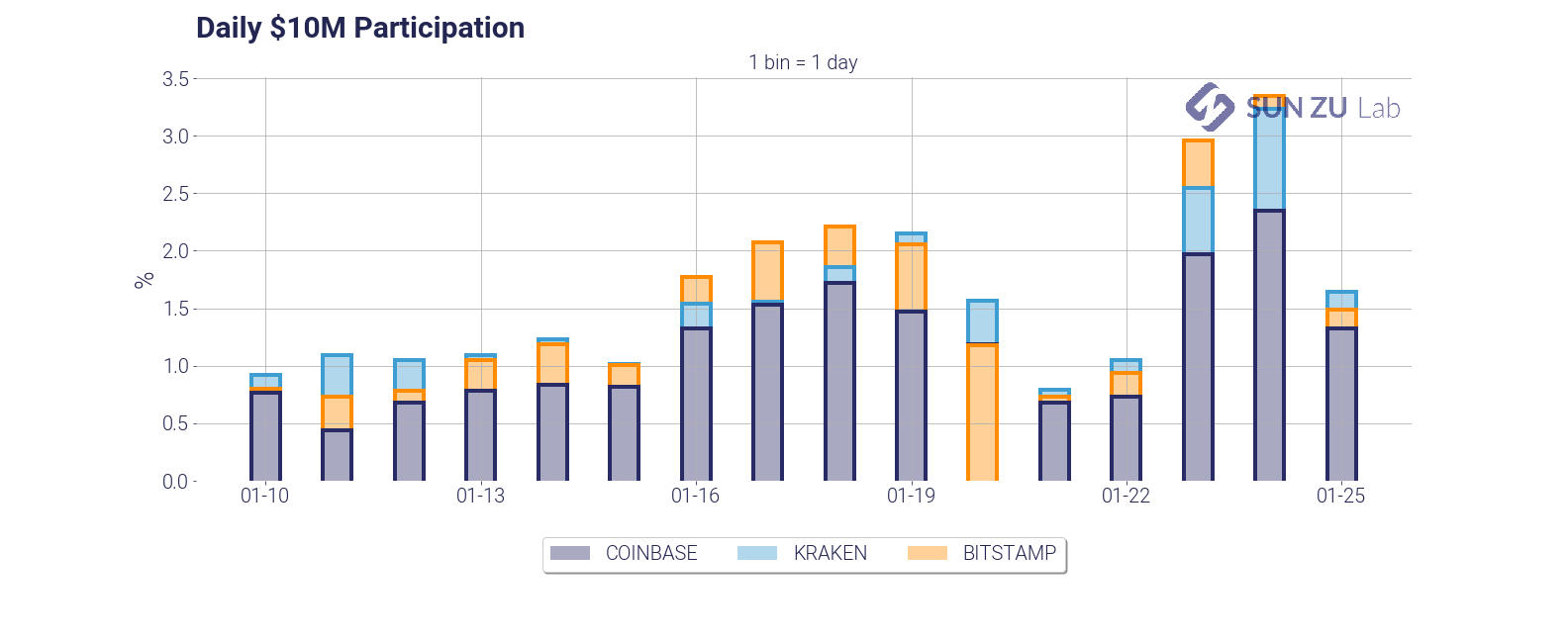

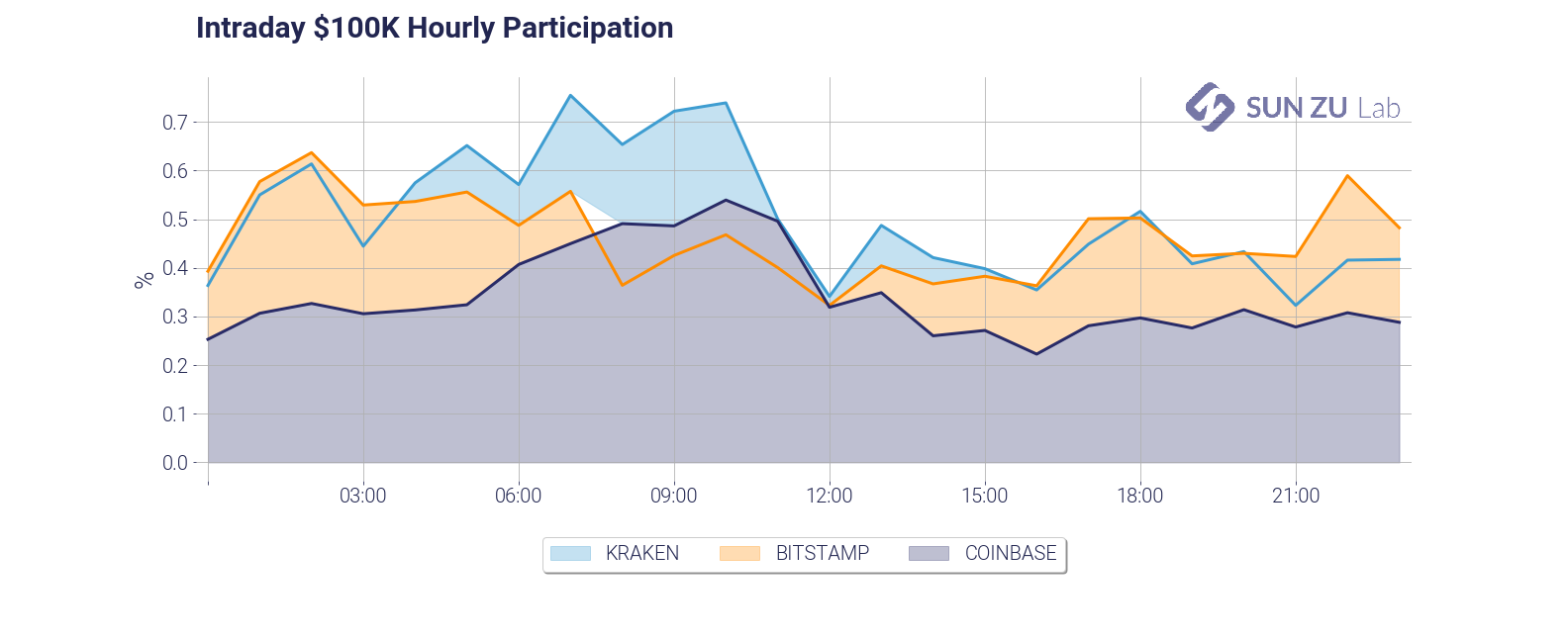

- daily $10M and intraday $100K participation:

Those two charts give two measures of market participation. First, we answer the question: how much volume does it take on a given day to fill a $10M order? As you can see it takes anywhere from 1% to 3% of the daily volume, on each exchange taken independently. Practitioners in traditional markets advise their clients to never cross the 15%~20% threshold. In the case of BTC on those three exchanges, roughly 10 investors with a significant order would be enough to “drain” available liquidity. The second chart is an examination of the same question, with a shorter time frame (1 hour), and a smaller size ($100K). Markets seem to be amply capable of absorbing repeated $100K orders.

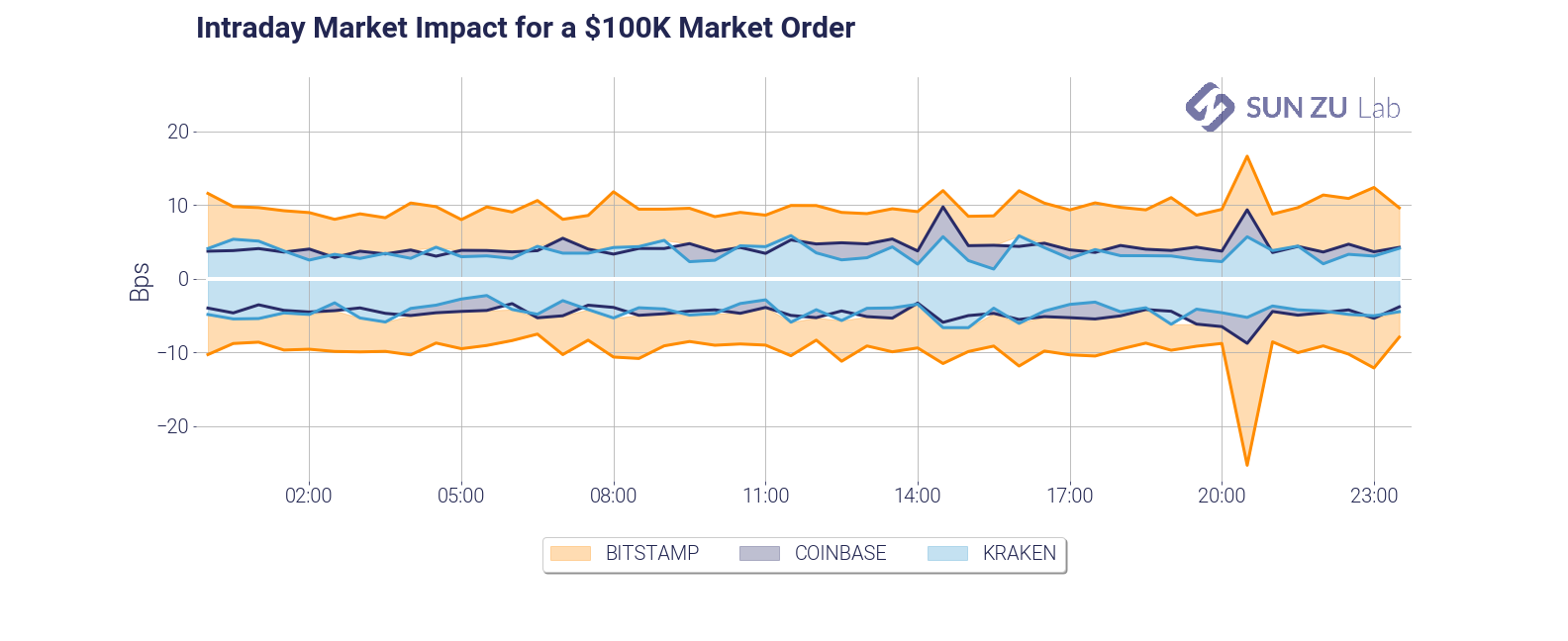

- intraday market impact of a $100K order:

This chart is a slightly different take on market impact. It answers a different question: how much adverse price movement would a $100K market order create? This gives a measure of market depth, which as you can see is fairly stable in time but quite different across venues.

- intraday ratio between traded and available volume:

By definition, each trade “consumes” part of the visible liquidity. What ratio of the liquidity available is consumed, and how fast is it replenished? The chart gives an answer intraday. As can be seen, there seems to be a somewhat constant rate of consumption and replenishment, something which is somewhat surprising. Again, we will absolutely look at this in deeper detail in due course.

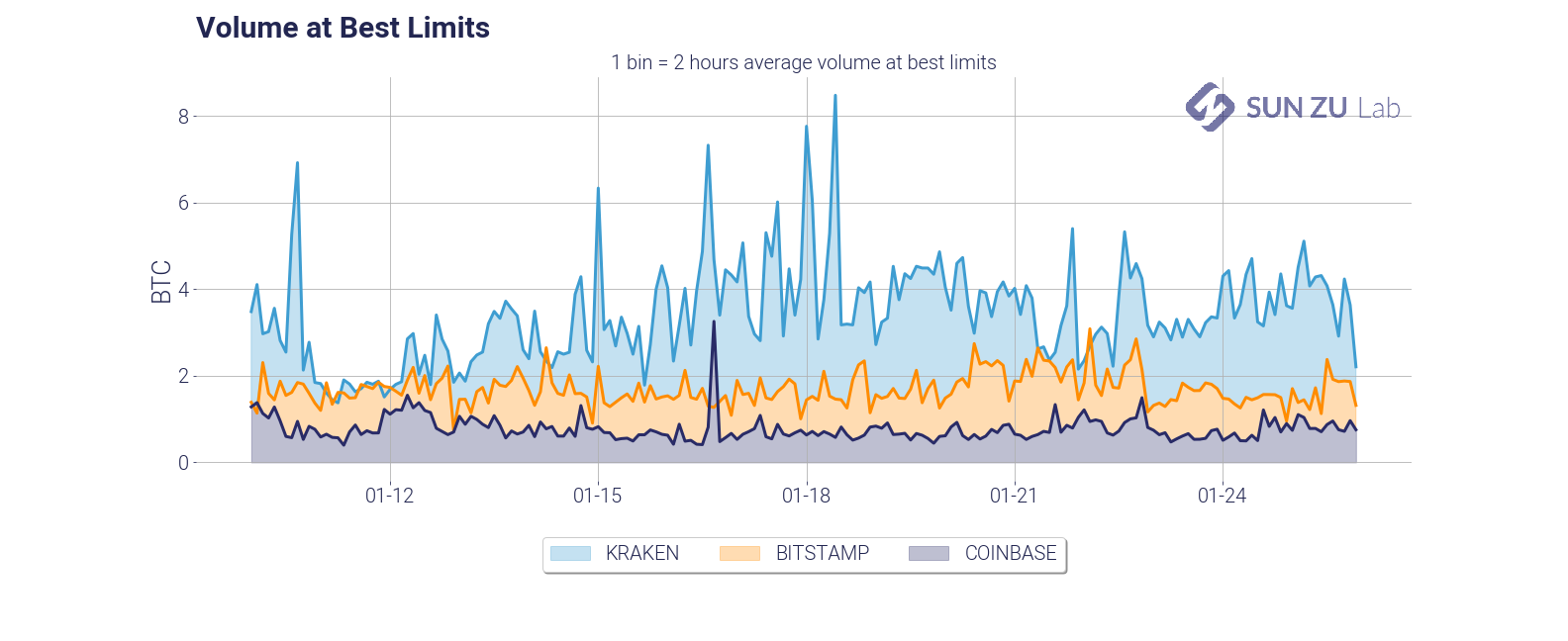

- volume at best limits (daily):

This chart presents a view of the total size available at best limits, in each of the individual order books. It is useful to monitor absolute levels of “aggressiveness” from market participants, and patterns in the overall migration, if any, from one venue to the next.

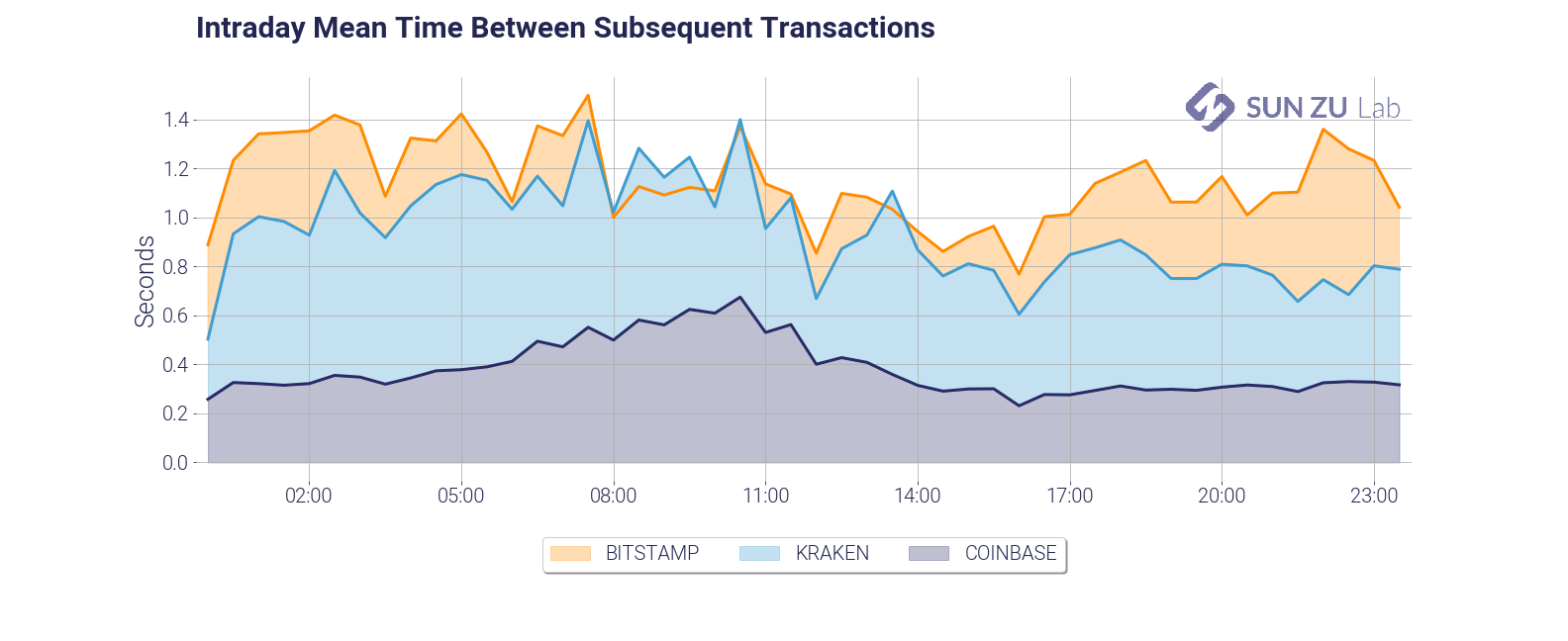

- intraday mean price difference and mean time between subsequent transactions:

Those two charts present an introduction to order book velocity. Each venue has its core client base, and those may have very different trading habits. Those habits are also constrained by venue-specific factors such as commissions, API throughput, matching engine performance, etc. Investors may gain valuable insights by qualifying each venue’s reactiveness and specific velocity.

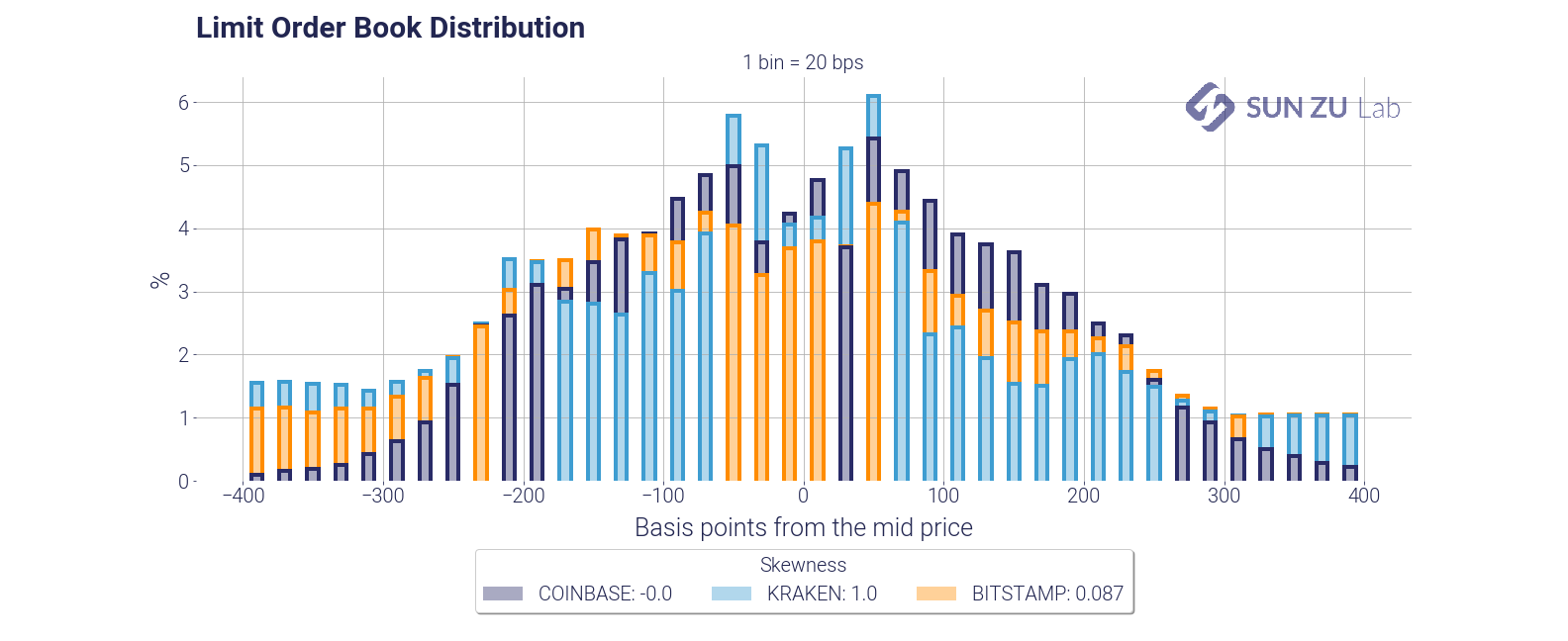

- limit order book distribution at +/- 100 bps and +/- 400 bps from mid-price:

Those charts present the distribution of each order book around mid-price, for a depth of 100 bps and 400 bps. There is a wealth of information to be extracted from those distributions. Here are two examples.

First, they indicate how participants think about risk beyond the first limits: are they placing a lot of orders away from mid? if so, are those significant compared to the best limits?

Second, how does each venue compare? Am I more likely to find liquidity at 50 bps from mid on Coinbase or Kraken? What about 100 bps?

Market makers, speculators, institutional investors have very different trading strategies. Market makers may be interested in price discrepancies, which would lead them to participate symmetrically from mid-price. Institutions may be more buyers or sellers at different times. In each case, they would presumably occupy one side more than the other. Although the averaging in the above charts provides a lot in readability, it is also the source of much “compression”. We have a lot more to say on order book dynamics, and in fact, it will be the subject of an entirely new report soon!

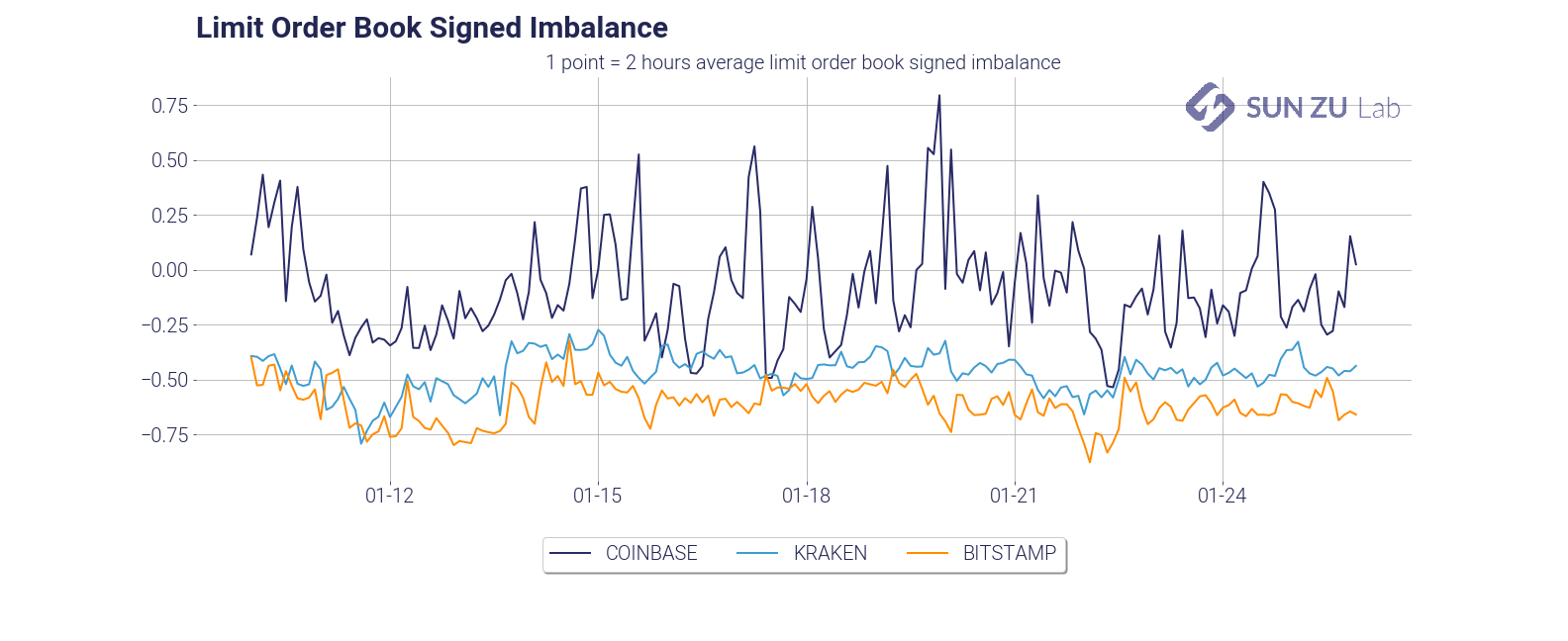

- limit order book imbalance:

Popular wisdom would have that a trending market shows asymmetry in liquidity. Well, unfortunately, this is not quite as simple as that. The graph above represents the order book imbalance by trading venue. Order book imbalance is defined as (Qa — Qb)/(Qa + Qb), where Qa is the total quantity, available at 100 bps from mid on the offer, and Qb is the total quantity available at 100 bps from mid on the bid.

Imbalance oscillates between -1 and +1: a market with no bid (Qb = 0) has an imbalance of +1, and -1 for a market with no offer (Qa = 0). An imbalance close to 1 means the order book is dominated by offers and vice-versa.

It is very apparent that the three exchanges have very different imbalances. At 100 bps market depth, Coinbase is mostly an “offer” market (with variability), whereas Kraken and Bitstamp are mostly “bid”.

- average market depth:

Total visible liquidity is a very natural question: how many bitcoins are available in each order book? Those two charts present two different answers to that question. On the left, absolute size at 100 bps, on the right intraday depth at 10bps. Those can help provide first-order estimates of impact: 100 BTC can be executed with a max impact of 50 bps; at any time, an order of 10 BTC should not be filled more than 10~15 bps from mid.

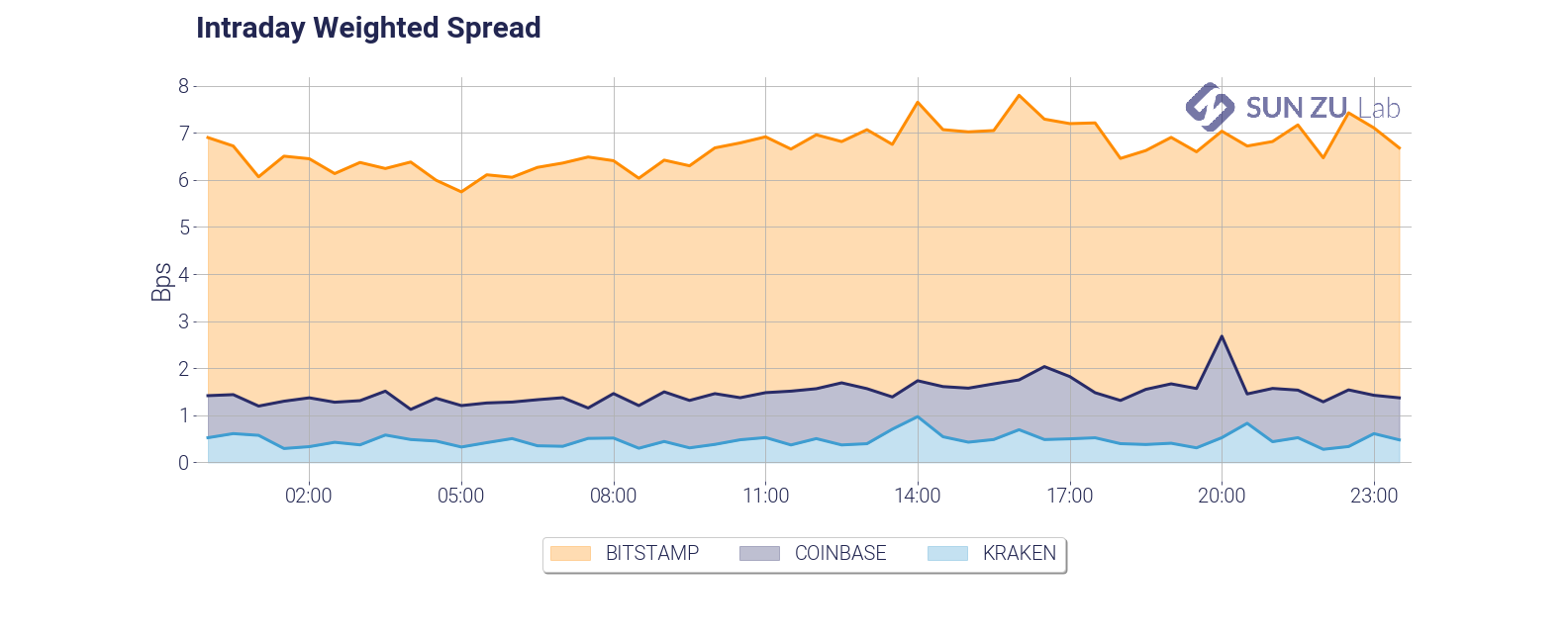

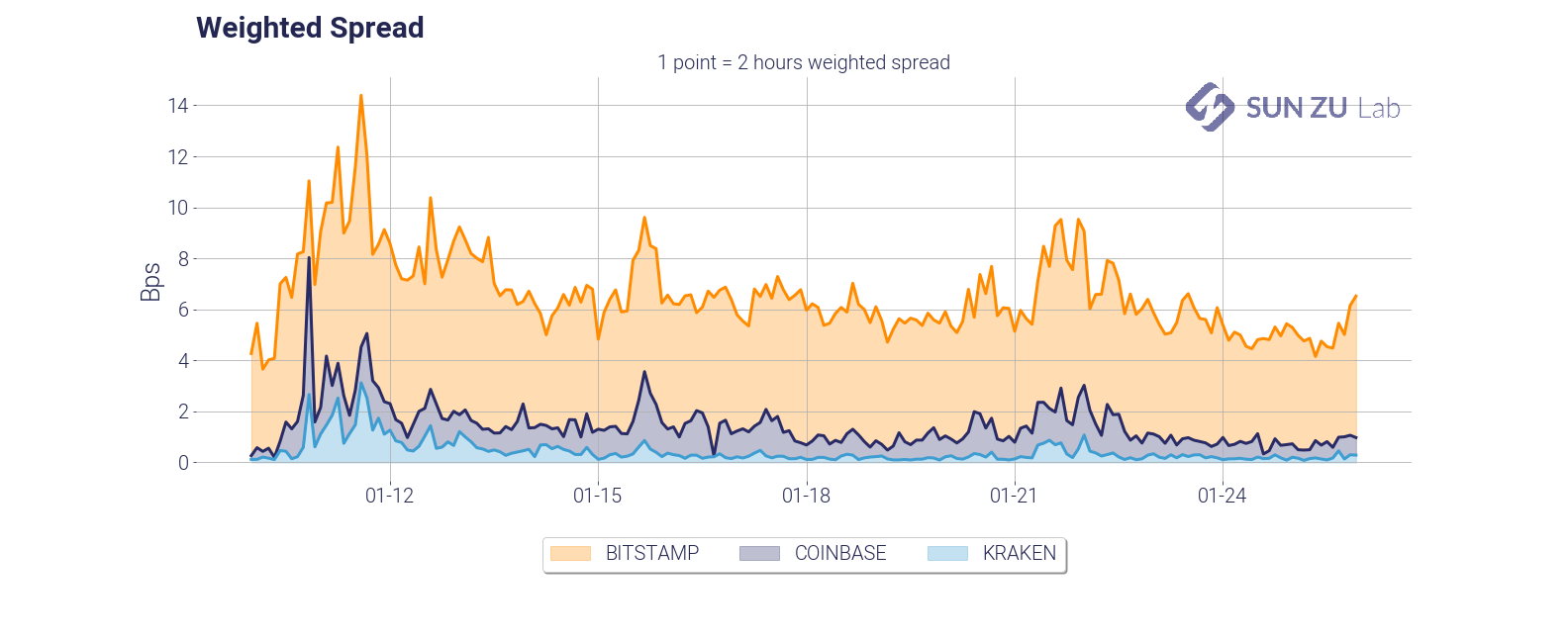

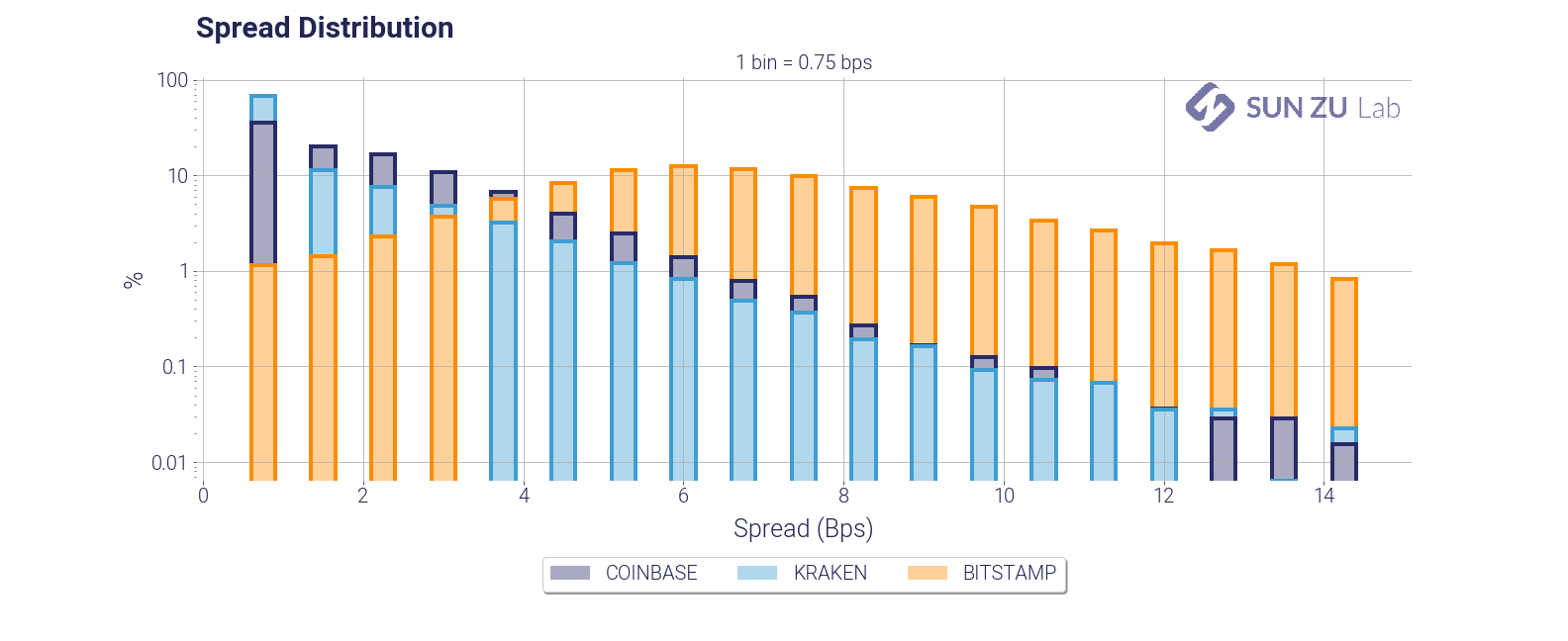

- spread and weighted spread distribution:

Of course, no study of liquidity would be complete without spread analysis. Above are time series of the weighted spread, showing intraday and daily dynamics. Unsurprisingly the weighted spread deteriorates quickly with volatility (early days in the chart). The charts below enable comparison between a simple spread and a measure weighted by the total quantity on best limits (bid + offer):

It can be seen quite easily that exchanges have very different order books.

Now this is a long list of charts and tables. You may get a sense that a lot of it is repetitive. We would argue that it is not, quite the contrary. As was said earlier liquidity is an elusive parameter, and in the world of digital assets it is bound to evolve very quickly. Monitoring and understanding it appears to us an important prerequisite for traders already active in the space, or even for “crypto curious” i.e. investors or institutions interested in the subject but not yet in a position to transact.

What is prime brokerage and how does it apply to digital assets?

There is a lot of talk in the crypto economy about prime brokerage: many participants frame themselves as “prime brokers” (PB), with the usual superlatives. What exactly are we talking about? A broker is an intermediary between a buyer and a seller: for a multitude of reasons despite the costs involved, it often makes sense to “intermediate” a transaction. This is the case for corporate mergers & acquisitions, real estate, a large fraction of products in capital markets, auctioning art, etc. But what are the prime services offered by a broker beyond execution (i.e. the matching of buyer and seller)?

In traditional finance, prime services include the following:enhanced execution services: those may be for example access to a low latency environment, co-location at an exchange data center, custom-made trading algorithms that may not be widely available to the broker’s client base, etc. In some instances, a PB might even allow a client to trade under the broker’s membership for better performance and/or lower costs.

- custody of assets: this is fairly customary, most broker-dealers offer custody services as part of an integrated solution (but sometimes using a distinct legal entity). Client accounts may be co-mingled (all in the same place) or segregated (in individual accounts). Co-mingling assets is practical and cost-effective for the PB (for example for settlement and delivery) but presents an element of risk for the client (in 2008 some of Lehman clients discovered that their assets were not segregated. As a result their claims was much harder to enforce in the liquidation proceedings). Segregation dramatically facilitates property claims in case of default but is regulatory and operationally more costly.

- operations: commonly referred to as “back-office”. A PB will make its back office available to address the settlement needs of its clients, from basic cash and derivative settlement to OTC reconciliation, margining, and corporate actions. Back-office operations are a very tedious universe. While many operations are “straight-through”, a lot of situations arise that need manual intervention. A PB will essentially allow an investment fund to outsource all its “ops” department, thereby significantly reducing its fixed-cost base.

- portfolio valuation: third-party valuation is a basic requirement in the world of asset management. PBs fulfill that need for their risk monitoring requirements but also the benefit of final investors.

- funding (i.e. secured lending): that’s a big one. A lot of asset managers, especially speculative hedge funds, employ leverage. The principle is quite simple: the fund borrows money to buy assets, those assets are then deposited as a guarantee against the loan. The interest rate paid for this loan reflects the type of assets, their liquidity, and naturally includes a commercial margin that is client-specific. Funding is a very important part of a PB revenue mix because of its diversifying nature. Execution is a transactional business: no trade, no gain. Funding is an accrual stream: the simple carry of a position brings revenues day after day until the position is unwound.

- short-covering: for a portfolio manager trying to gain a short exposure in the market, the pre-requisite is finding the right instrument to build this exposure. Today “naked short-selling” -i.e. the sale of an instrument without having secured the possibility to deliver- is mostly forbidden. For example, a stock cannot be sold short if it hasn’t been “located” to borrow prior to the sale. Being able to locate inventory at a fair price is a critical competitive advantage for PB. A client can naturally request a locate from intermediaries other than its regular PB, but the cost is most certainly higher and practicalities can be tricky (on-time settlement for example).

- regulatory reporting: not much to detail here. The trend is towards more of this, outsourcing this function is a no-brainer for many clients.

- risk management and reporting: risk management is naturally a function of each client’s strategy and mandate. There are three reasons however why PBs have stringent risk management practices in place: i/ they need to make sure that they can survive a client’s default, and if possible even anticipate it so that market-wide damage is minimal; ii/ in the presence of leverage, there is a credit element to risk management: a sudden market drop could result in dramatic losses because of leverage; iii/ regulators impose it, implicitly as a way to overlay a third-party risk monitoring layer. Many hedge funds are unregulated: final investors and regulators can find reassurance in the fact that well-established PBs keep a close eye on their risk engagements.

- fundraising: because of their extensive connections with final investors, institutional and otherwise, PBs routinely help their clients find new money.

- synthetic format: prime brokerage was historically a cash business i.e. clients would physically buy and detain the assets. With the development of derivatives, a new format emerged: “synthetic prime brokerage”. In a synthetic arrangement, the client doesn’t hold the assets. Those are on the PB’s balance sheet and the client holds a derivative that mirrors the portfolio’s exposure — it usually takes the form of a total-return swap (TRS). The synthetic format offers many advantages from a client standpoint, in particular its simplicity. However, this simplicity comes with an additional layer of legal complexity due to the fact that a derivative product is involved.

Now, what about the crypto space? Are prime brokers there close to providing prime services to their clients? Not by a long stretch. One could argue that there are in fact only very few true prime brokers for digital assets. Some functions are highly relevant (e.g. execution), some don’t even have an equivalent, for example regulatory reporting which is non-existent (today).

The most fundamental interrogation is this: do digital assets possess intrinsic characteristics that would prevent nascent digital capital markets to grow and converge towards their cousins on traditional instruments? Well, at SUN ZU Lab we don’t think so, quite the contrary. In principle, we think digital assets have tremendous potential to equal and even surpass some traditional assets. With two caveats:

- the industry needs to aggressively embrace self-discipline if not self-regulation: conflicts of interest are widespread, opacity is the rule, not the exception. Embracing self-regulation will promote cooperation and contribute to forging a common vision. In turn this vision will help consolidate relevant technologies, and forge a path to much needed standardization.

- market participants need to make peace with traditional regulation. Not all of it is relevant or applicable, but regulators worldwide care about only one thing: protecting investors, especially non-professional ones. The digital asset industry need to recognize this fact and make it its mission to help.

Physical delivery and what it means for digital assets

If you ever wondered about the difference between “cash settlement” and “physical delivery” in the world of derivatives, 2020 was a crash course on the matter. Yes, this was the year of negative oil prices, and many will remember those painfully. If Y2K was about fixing a trivial shortcut in date formats, you can bet software developers and risk managers alike were never quite ready for negative oil prices in their systems and scenarios.

What was it about anyway? As always when a situation is more or less “impossible”, there were several converging factors to get to the impossible. The CFTC report names three: an already oversupplied global crude oil market at the beginning of 2020, an unprecedented reduction in demand caused by COVID-19; and concerns about the availability of global crude oil storage.

But what has storage space got to do with this? The missing link is that products exchanged on oil are in fact “physical delivery” futures. That is when a future expires, the buyer physically receives a fixed number of barrels. Furthermore, to standardize the market, deliveries are accepted at only specific locations (see for example the paragraph “delivery procedure” for NYMEX Crude Oil). Any disruption in the flow of oil and storage capacities are easily saturated. In March, this is exactly what happened: a sudden collapse in demand led to a withdrawal from buyers. Markets participants equipped with adequate facilities could collect deliveries and wait it out by keeping their inventory in place. However for participants not properly equipped, holding a future contract meant taking delivery and that was simply not possible because storage at designated facilities was not available. Speculators and traders routinely trading oil without consideration for physical inventory were caught in a “fire sale” spiral in the days leading up to expiry, driving prices in uncharted territory.

You’d be tempted at this point to conclude that physical delivery is a nuisance. Not quite. First of all, it should be pointed out that the commodity market being what it is, physical delivery is the most natural outcome of a transaction between a buyer and a seller. Indeed, “cash settlement” is out of place: it encourages speculation without any consideration for the geographical location of products being traded. And then there’s the other major advantage of physical delivery: it forces convergence between the expiry price of a derivative and the price of its underlying.

Consider for example a future on a stock, cash-settled at expiry. The final reference price of the future is the closing price of the stock (as is the case in the US for example). If you buy the future at $100, and the underlying stock closes at $110 on expiry, you will receive $10 as a final margin call and that’ll be the end of it. If the future is physically delivered, you will receive the stock upon expiry, and the final price being $110 this is what you’ll have to pay. The $10 margin call in your favor means that you effectively bought the stock at $100 - that makes sense because that was the price of the future when you entered the position.

In a world of cash-settled derivatives, the expiry price is set by reference to the underlying, but it doesn’t mean that you can acquire (or dispose of) the underlying at this price. There can be a divergence between those two prices. In a world of physical delivery there cannot - you automatically get ownership of the underlying at the expiry price.

To be specific, let’s take BTC as an example, and in particular the CME BTC Future. The future expires on the CME Bitcoin Reference Rate (BRR), defined as “the aggregation of executed trade flow of major bitcoin spot exchanges during a specific one-hour calculation window“. The future is cash-settled. Upon expiry, CME will calculate a price based on its BRR methodology and will settle the final margin call using that price. The problem is: how do you replicate this price? If you hold a delta-neutral position in bitcoin (long BTC, short future), at expiry you need to unwind the cash BTC leg at the exact same price as the future. That means you need to sell your BTC at the BRR price, no more, no less. This is an ambitious proposition: it implies that i/ you are connected to all relevant exchanges, ii/ you are technology-savvy enough to replicate the BRR real-time exchange allocation, iii/ you can place orders and received executions at the right price at the right time on each exchange. If the BTC future was physically delivered, you would have absolutely nothing to do - you would automatically receive proceeds from delivering BTC as part of the short future.

In traditional markets, this is a well-known problem that occurs for all derivatives that are cash-settled on “exotic” references. For example in France, the CAC 40 index futures settle on an average price over 20 minutes (“Exchange Delivery Settlement Price“). Tradability of the EDSP is an issue for all participants, even those technologically equipped are subject to a convergence risk. This risk is vastly mitigated when settlement prices are set through an auction because the fundamental mechanism of an auction means that everybody is fully served at the same price or the auction doesn’t conclude. Nothing of that sort for BTC or other digital assets: no closing auction, no physical delivery which means that future traders must cope with a simply unpredictable convergence risk.

Now you might wonder…why does it matter? After all, this doesn’t prevent trading, nor does it affect the overall level of risk associated with digital assets. Well, it does affect the ability of the digital industry to introduce secured lending and through it credit-mitigated leverage. I have explained before how the convergence formula of a future contract enables un-coupling between market and credit risk. This however is only possible if convergence is certain. If it is not, secured lending introduces a market risk component that is likely to be unacceptable for yield-seeking lenders. Physical delivery would make secured lending much safer and in turn would pave the way for a truly new chapter: securities financing.

Is Bitcoin a safe haven in times of crisis?

Background

Bitcoin and digital assets in general have been presented by some as credible alternatives to institutional finance as we know it today, with its strengths and especially its weaknesses — widely exposed and documented with the 2008 crisis. The idea of a mechanized trusted third party has a certain appeal. Removing human arbitrariness and intermediaries in the management of money would make it possible to get rid of what is perceived as cumbersome state control and to guard against the stranglehold of the financial industry, which is accused of taking a large share of profits and caring far too little about consequences. Gone are the days of lax inflationary policies steered by a central bank subservient to political power. Not to mention the possibility of keeping one’s savings right under the nose of bankers and tax officials.

There is much to be said for a world in which dehumanized algorithms, complete anonymity and decentralized governance have become the norm, a world that is unlikely to deliver on the promises its proponents put forth, both in terms of efficiency and equity — not to mention questionable transparency, which is high on the list of criticisms from institutions today. But some proposals are worthy of attention and, at the very least, of consideration. One of them is the following: are digital assets likely to offer true storage of value, independent and uncorrelated to traditionally available assets (shares, bonds, gold, etc.)? The example of countries with failing institutions is often cited, such as Venezuela or Nigeria. Bitcoin would be a way to hedge against immediate monetary turbulence, delirious black market exchange rates etc. With the coronavirus crisis, this question extends to developed economies: would it be in the interest of an individual or institutional investor to transfer part of his savings to bitcoin in anticipation of a collapse of traditional assets or even the financial system as a whole?

Let’s eliminate immediately the hypothesis of the collapse of the system: if such a catastrophe were to occur, the consequences would be sufficiently devastating to take with them the very existence of a “safe haven”, a compartment protected from the ambient deflagration. Instead, we will try to answer the question of the allocation between digital currencies and traditional financial assets.

Examining this idea requires some work, which we will carry out in a very basic way. The question can be rephrased as follows: “if I had chosen to invest part of my assets in certain digital assets, would I have done better than traditional markets? ». We consider this problem through the examination of three elements: the performance of digital assets, their volatility and their liquidity.

Performance is used to determine whether or not an investor would have avoided a decline or even benefited from a rise if he had “pivoted” to a digital asset. Volatility gives an idea of the carry of a position, i.e. its variation over time: is it really a smooth ride? Liquidity is a slightly more technical notion: when the market panics, is it still possible to carry out transactions or, on the contrary, does everyone run away?

A word on the notion of “safe haven”. This concept captures the idea that there are assets — financial or otherwise — that provide safety in the event of financial turbulence. The perception of security can be linked to objective or subjective criteria. When investors bought US and German debt in the sovereign crisis of 2012–2013, the perception of security was linked to an objective factor, the economic resilience of those economies and the very high probability that governments would be able to meet their commitments. Conversely, the status of gold as a safe haven has no basis in reality today. When world currencies were pegged to gold in the Bretton Woods world, gold was the ultimate security since it was the assurance of being able to buy any currency at a fixed price. In the modern world, where exchange rates are floating, possession of gold does not provide any real safety. We are in the realm of self-fulfilling prophecies. Everybody thinks that gold resists better when the markets fall, so investors buy it as soon as tensions appear, and bingo we see a posteriori that the predictions have proved to be correct. Another important point is that the use of safe haven assets is limited in time. Nobody takes a position on gold to protect a portfolio over 15 years. Anyone who is significantly invested in gold for 15 years does so to diversify their risk in an allocation strategy, not to protect themselves from volatile periods. A safe haven plays a role episodically, mainly when the markets are nervous. It is therefore at this time that one must look closely, and this is why the recent crisis offers a particularly relevant point of observation.

A quick methodological note: the S&P 500 is modelled by its most liquid exchange-traded fund (ETF), known as the Spider (ticker SPY, $257 billion in assets as of 4/24/20) Gold is modelled by the sum of the two largest physical ETFs (tickers GLD and IAU, $80 billion in assets). US government bonds are modelled by the iShares 7Y-10Y ETF (ticker IEF, “only” $21.5 billion in assets). The BTC/USD and ETH/USD data are from coinmarketcap.com, volumes were divided by 10 to account for the numerous and documented manipulations of various exchanges on their data. The factor 10 is arbitrary but regularly appears as a working hypothesis in studies on the issue (but in fact the absolute value of the volume is of little importance here). The prices are the closing prices, and of course all execution issues are neglected. Access considerations are also neglected: the products used here are easy to access, anyone can open a securities account with an online broker within a few days. Access to digital assets is not yet so democratized. All this is therefore very simplified.

Performance

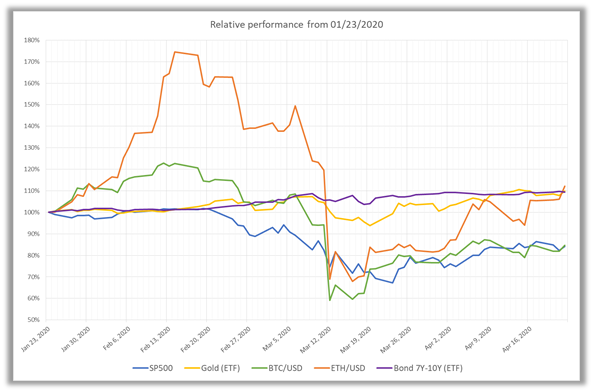

The performance we are interested in is the one surrounding the recent crisis. An investor who has been carrying bitcoin or ether for a long time is doing so for reasons that are not our concern here. Here is the relative performance of the 5 assets between 01/23/20 and 4/22/20:

The charts speak for themselves: the crisis reached its climax on March 12th, after the US President announced, quite unexpectedly and without any consultation, the closure of US borders. All assets drop sharply, except bonds, which have always been considered safe among the safest. Surprisingly, gold is also falling significantly. It appears that bitcoin or ether would not really have been an insurance policy. The BTC holds better over the few days before the crash, but drops lower immediately afterwards.

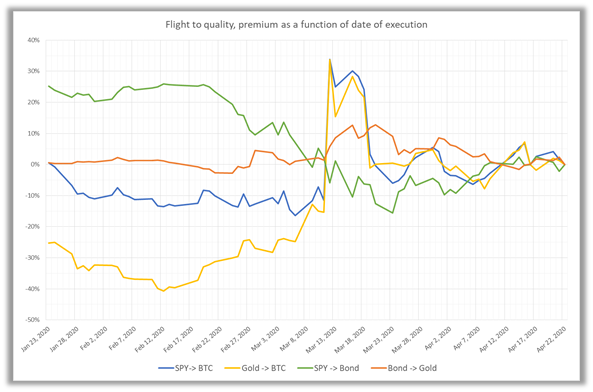

Another way to answer the same question is to ask what was the “safety premium” for investors who made the right choice? Prior to March 12th, investors were given a free hand to choose the best investment if they sensed upcoming turbulence. This behavior, called “flight to quality”, is widespread. Before mid-March the pandemic was beginning to show its effects in China, nervousness about the impact and spread of the disease was beginning to show. A prudent investor could have chosen to transfer some of his positions to assets considered safer, such as gold or US sovereign bonds. The outcome would have proved him right… The following graph shows the premium he would have captured:

Precisely, the green curve reads as follows: an investor who would have transferred his position on 01/23/20 from the S&P 500 to US bonds would have captured a 25% gain between 01/23/20 and 04/22/20 (compared to a situation where he would have remained invested in the original support). In concrete terms, he would have avoided the massive decline around March 12th. If he had taken this decision later, at the end of February or the beginning of March, he would still have gained 10%. The graphs show the exact premium captured for having changed support, depending on the date the change takes place.

It appears that the choice to pivot from S&P 500 towards BTC (blue curve) only pays off on March 12th, when the BTC loses 37%. Pivoting from gold to the BTC would have been even worse off (yellow curve).

Note that after the crash, the decision to stay invested in the original support or to pivot is of little importance: from about March 26/27th, the curves are rather undifferentiated. Moreover, the bond > gold pivot (orange curve) turns out to be winning at almost any time…

Volatility

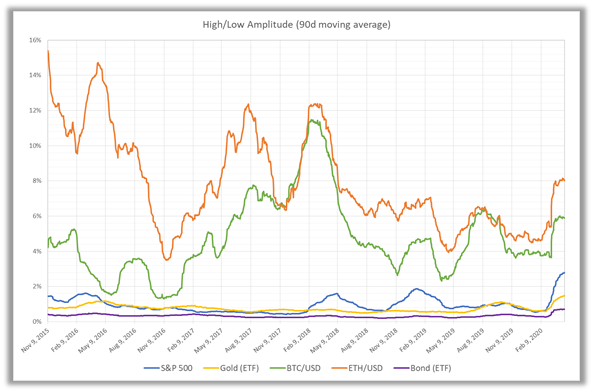

To examine volatility, we could use the financial version, i.e. the annualized standard deviation. But for a change we will use a more intuitive measure, the intra-day variation. The following graph shows the 90-day moving average of the daily high-low amplitudes of the 5 assets:

NB: the starting date is arbitrary, it was chosen to visualize about 5 years of data.

This is an intuitive rather than a financial measure of price variability, which can be understood as follows: since May 2018, on a “normal” day, the BTC has varied on average by 4% to 8% between its highest and lowest price. In contrast, the S&P 500, gold and bonds only vary between 1% and 2% (or even less). In March, we see a significant increase in these figures, which corresponds to higher intra-day volatility, i.e. the effect we want to measure.

Indeed, carrying a BTC or ETH position is not a smoot ride compared to other asset classes: the amplitude of movements is 4 to 5 times greater. Incidentally, dealing in BTC requires careful monitoring compared to traditional assets that have the good taste of moving less quickly and whose markets are closed several hours a day.

Liquidity

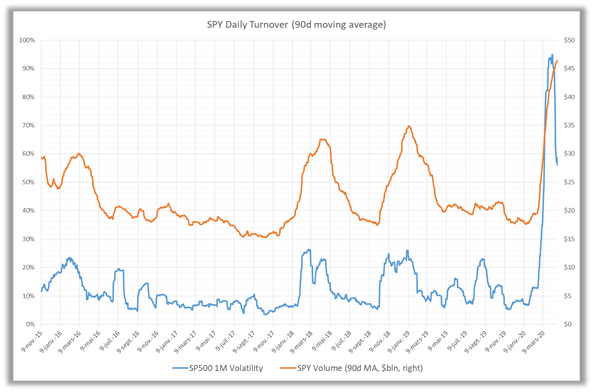

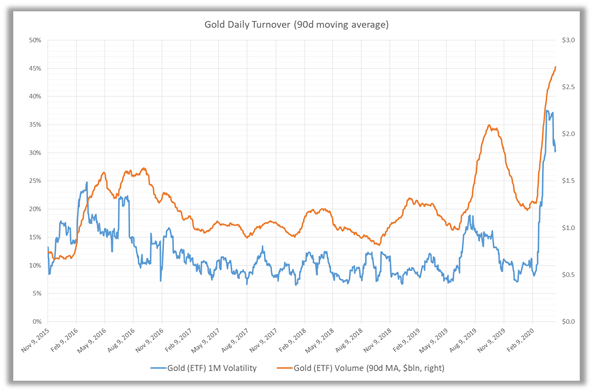

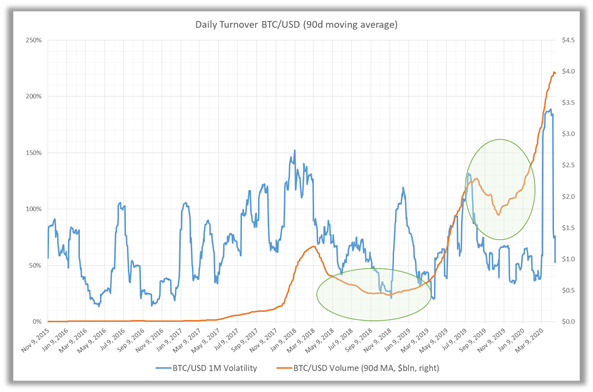

Finally, let’s look at liquidity, characterized by daily volumes. This is an ex post measure of liquidity, precisely that which has been expressed in the form of transactions. We could also look at an a priori measure, the liquidity available before execution in the order books of exchanges, but that is a more complex task…for another time. The graphs below show average trading volumes (90-day moving average) over a period of about 5 years, with 1-month volatility as the second axis:

The S&P 500 ETF is one of the most liquid instruments in the world, with $20 to $30 billion traded daily. The causal relationship between volatility and volume is immediately visible. Same presentation for gold:

The ETFs under consideration only trade around $1 billion a day, but the causal relationship is still perfectly visible. NB: the volatility seems much more uneven than that of the S&P 500, but this is an optical effect related to the smaller scale.

Here is finally the same graph for the BTC:

If we had to (re)confirm the much more volatile behavior of the BTC, here it is: volatility episodes are frequent, acute and independent of those of traditional markets. But this graph raises many questions.

Compared to previous ones, it immediately appears that volatility/volume causality breaks down. Some peaks in volatility are not accompanied by any increase in volume, and conversely the volume seems to grow by itself…

The two areas circled on the graph are anomalies, presumably explicable by the fact that the officially announced volumes are vastly overestimated and that the magnitude of the “ghost” volumes varies over time. Both the S&P 500 and gold (and the bond ETF, not included here) show a fairly stable “structural” liquidity: when volatility eases, the average volume falls back to a floor. The fact that it falls very sharply on BTC between May 2018 and March 2019 suggests that the “true” floor is much lower. Similarly, in the second half of 2019, volumes return to average levels for the S&P 500 and gold. Nothing comparable for BTC (or ether), growth is exponential. It is not justified by any measure of volatility, nor by any other market event or media coverage.

Conclusion

To the question “Is BTC a credible alternative to the volatility of traditional markets?” it is fairly easy to offer a negative for the recent crisis. It is certainly an isolated point — but absolutely significant in view of the magnitude of the crisis. There is no doubt that gold and sovereign bonds are still the “safe havens” they have long been. On the other hand, the liquidity of bitcoin (and ether) is still problematic, and does not exhibit an explainable pattern in view of the proven behavior of the investment community as expressed every day elsewhere.

Liquidity and order book distribution

When we formed the team to launch SUN ZU Lab, we had mostly one question: how liquid are crypto-assets, and if there is indeed liquidity to be found, to what extent is it different in quantity or quality from what we have seen in traditional markets for 25 years?

“Liquidity is defined as the ability to buy or sell an asset for large size without significant adverse price movement.”

This straightforward question is not so simple and has many ramifications. Indeed if you can qualify and quantify liquidity, then you should be able to execute better (i.e. with smaller adverse price movement). Therefore whoever starts with order book analysis should be ready to go all the way to real-time “smart” order routing.

We are not the ones at SUN ZU to shy away from a challenge like this, so we decided to take the first step and share our results regularly. Among the many insights we will explore and comment, we would like to start with a fundamental element: order book distribution.

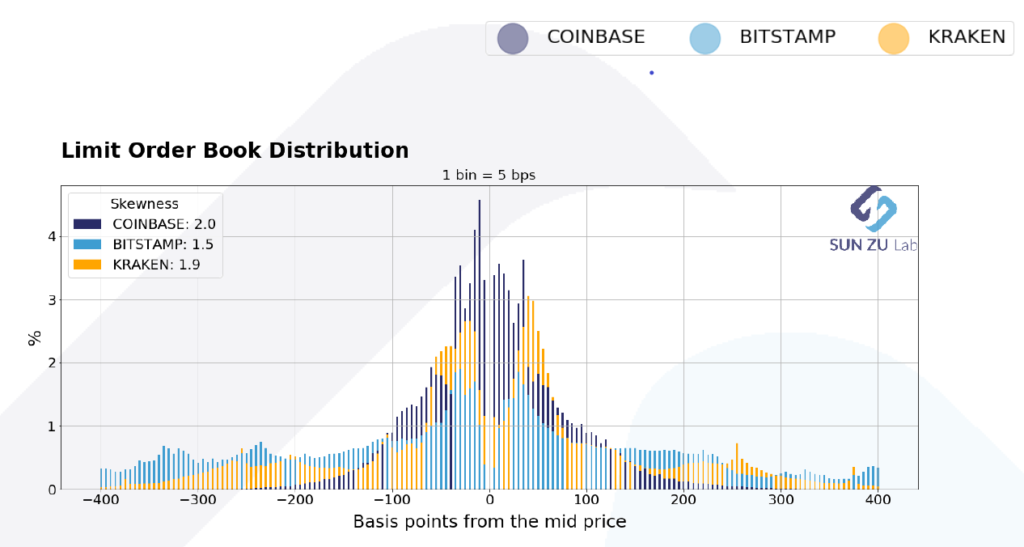

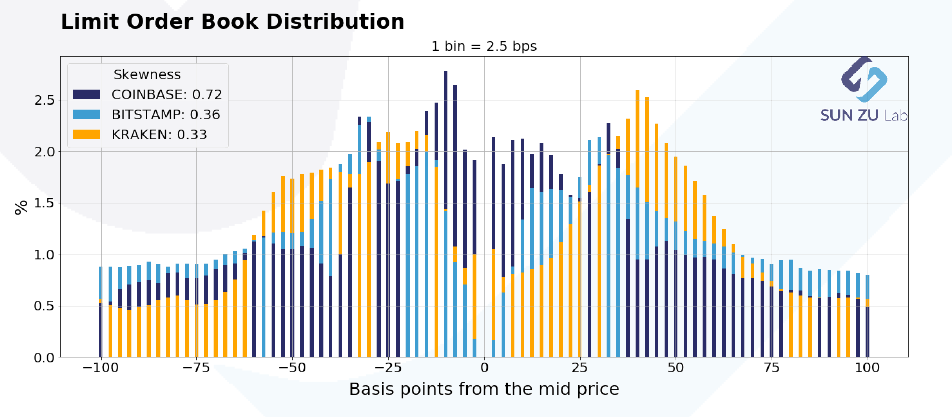

The chart below shows how liquidity aggregates (those are excerpts from our first public research report available here) around mid-price. To get a sense of this, we plotted the distribution of orders in the BTC/USD order book for three exchanges (Coinbase, Bitstamp, and Kraken) and averaged the results for the first half of September:

Order book distribution at +/- 400 bps from mid-price. Data from Kaiko.com.

This chart reads as follows: each bar represents the proportion (in %) of orders found at the given distance from mid-price (mid = (bid + ask) / 2). for example a 0.7% bar at -150 bps indicates that 0.7% of all orders in the price interval [-4%; +4%] can be found 1.5% below the mid-price. By construction, for each exchange, the sum of all bars equals 100%.

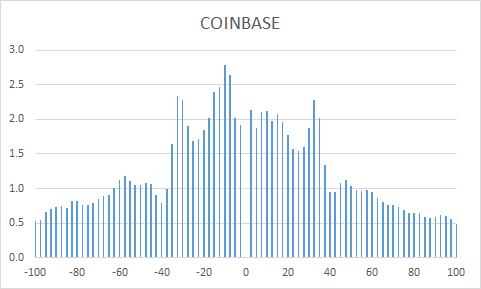

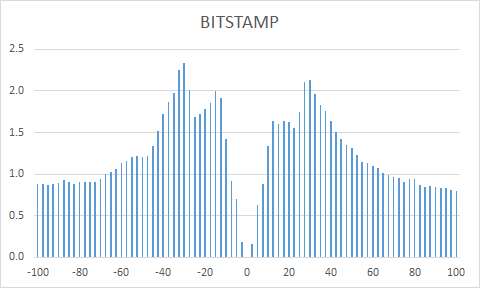

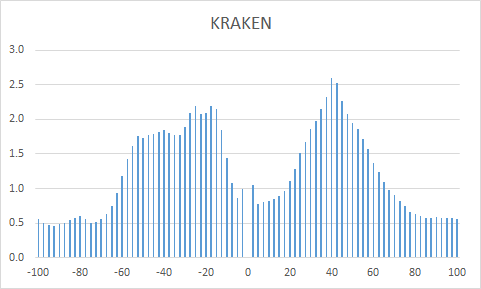

In fact, the above chart is the superposition of three individual pictures:

The benefit of layering the three graphs is to present an aggregate view of liquidity, and its partition across the three exchanges, with a single scale and a clear color-coding.

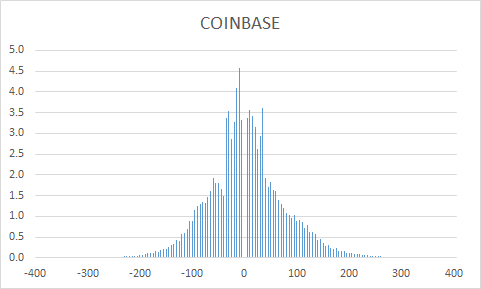

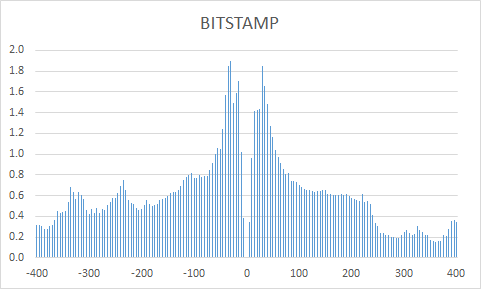

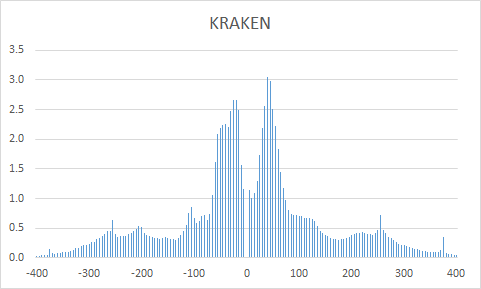

If we focus on a smaller interval, say [-1%; 1%], we get the following distribution:

Order book distribution at +/- 100 bps from mid-price. Data from Kaiko.com.

As before, this image is the results of layering three individual charts:

What’s the point of those charts? Why did we choose to aggregate data across exchanges and average through time? Well, the intent is to measure behavioral patterns from investors, on individual exchanges, and across the entire market (represented here by only three exchanges, more are coming). Here are a few points of interest:

- bell-shape curve: does a bell-shape curve make sense? Yes indeed: it is quite intuitive that the density of orders decreases away from the place where the action is taking place i.e. the mid-price. Yet differences are quite obvious when approaching mid-price: in some cases the available size in the book increases, in other cases it decreases. For example, the spread is much narrower on Coinbase than on Bitstamp or Kraken, it almost looks as if investors on Bitstmap wanted to stay away from the first limits in the book. Indeed, we intend to put much more work investigating those questions to deliver qualitative and quantitative insights that can help investors better understand and execute their transactions.

- speed of decay: is there information to be extracted from the speed at which liquidity decays? Absolutely: in a world of high volatility, many investors will want to place orders far away from trading levels to benefit from violent moves. This type of strategy is common in statistical arbitrage, it would be a surprise not to see something similar emerging in crypto-land. The “fatness” of the tails also serves as an indicator of “latent” liquidity i.e. orders waiting to be filled under proper circumstances.

- symmetry: is there a fundamental reason why those distributions should be symmetrical? Well, yes and no. Market makers tend to be symmetrical in the way they place orders. There is little sense in providing liquidity on one side and not the other (if you happen to have a commitment to provide liquidity you don’t have a choice in fact). Native buyers or sellers will on the contrary place themselves on one side or the other. Their relative proportion might therefore alter the symmetry of the order book. However, this relationship is severely weakened in a world where market manipulation is widespread: anybody can put massive orders for no other purpose than “window dressing” the book. Here again, more analysis is required to understand order-book dynamics.

- relative values between exchanges: exchanges have very different order books. Explanations for this can be diverse: fee structure, market-making schemes with specific obligations, more or less stringent market surveillance, minimum trading or maximum holding size, availability of leverage, etc. Because trading on a given exchange still requires fiat and crypto deposits and implies custody risk, comparing liquidity at different exchanges is quite important to choose a few in the many available.

- time-dependency: the data here is for the first half of September. SUN ZU Lab will produce those reports regularly, enabling comparison from one period to the next. If things change, for individual exchanges or on aggregate, it may indicate that liquidity is increasing, decreasing, or shifting places. Certainly something worth knowing.

- absolute vs. relative distribution: we have shown here relative distributions, i.e. no mention is made of the absolute size available in the respective order books. Also, we have looked at one asset only, BTC. Well, there’s only so much we can do here. Bear with us, we have much more to say on those subjects!!

Welcome to the wonderful world of liquidity analysis!

Everything you’ve always wanted to ask your crypto exchange

Whoever has been working in an investment bank knows that regulation is a big deal, even more so after 2008. By contrast, the world of digital assets is largely unregulated.

What is regulation anyway, why does it even exist? It could be argued that regulators worldwide have a single objective: to protect investors, small and big alike. What do investors need protection from? For the sake of simplicity let’s abstract this to the simplest notion : “information asymmetry”. Financial markets deal with information, assimilating information into price to obtain the “fair price” of a product or service. Information asymmetry means that one of the parties to a transaction knows more (or understands better) than the other, and as a result the price formed during that transaction is biased, resulting in a transfer of wealth from the less knowledgeable to the more knowledgeable.

“For those tempted to believe morons should lose their shirt, let me offer the following proposition: you always are somebody else’s moron.“

The information or knowledge we are talking about is somewhat specific. Two investors may differ in their belief that a particular situation will occur (for example XYZ stock price will go up), as a result will take different risks. Fine. But if a trader sells a complex product to a retail investor, it is most certain that the former has much better understanding of the associated risks, and may not be entirely forthcoming about those. This is the kind of asymmetry regulation is meant to address.

Coming back to the above transfer of wealth, one might argue the “fairness” of that transfer – which may or may not be part of the regulator’s mandate. What is beyond doubt however is that the global allocation of resources in the economy will be biased as well, resulting in inefficient and sub-optimal development (or unacceptable risks for unsophisticated investors). It comes as no surprise then that regulators’ first weapon is transparency, expressed as a disclosure obligation. After all the best way to make sure that everybody is on the same page is to force the more knowledgeable party to share information. That is exactly what has happened in the past 10 years in the realm of traditional markets. Disclosure goes a long way: from traders having to disclose their profit margin to clients, to financial institutions having to disclose employee compensation.

* * *

If we turn to the mostly unregulated digital eco-system, we should certainly ask the same question: if regulation served a purpose in traditional markets, specifically around the theme of transparency, shouldn’t we apply the same standards for the benefit of the largest number of investors? Presumably those would feel better protected and would increase their activity. In addition this sense of security would probably convince “by-standers” to join in.

Many argue regulation stifles innovation. But would transparency stifle innovation?

Well I confess that in my view transparency, whether volontary or imposed, is a fundamental component of “fair and orderly” markets, so I certainly hope we’ll see more of it. And in fact we might as well start looking for it right away.

If you were a trader in an investment bank, trying to become member of a new exchange, you would face a barrage of questions from all fronts: management, risk and compliance, even tax and accounting. Have you asked your crypto exchange the same questions? If those are legitimate for a regular exchange, why wouldn’t they be for any kind of marketplace? So what kind of information would a trader want to acquire i.e. what kind of question would you be wise to ask your crypto exchange (or any other intermediary for that matter)?

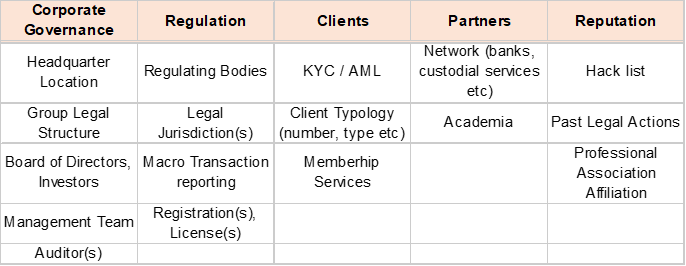

Let’s distinguish trading and non-trading. The table below gives a non-exhaustive list of non-trading relevant information:

It all has to do with common sense curiosity: who am I dealing with? what economic interests am I facing, what kind of legal protection am I entitled to (if any)? Does the exchange have a history of reputational issues such as hacking? What is the qualification of the management team and what governance are they facing?

It is not the point here to detail all the items, but to give a sense of the extent of information regulators would want you to have under the “disclosure” obligation before you open a new business relationship. By the way exchanges also want to know who they’re dealing with, that’s the point of KYC investigation. It’s only fair you/we return the questions.

One item might be surprising: “academia”. Well, believe it or not it is far-reaching. Many scandals in financial markets (and elsewhere) have emerged from the work of independent researchers. Exchanges worldwide routinely provide confidential trading data to the academic world to facilitate applied financial research. Such data is incidentally also made available to national regulators.

Is that mass of information readily available from traditional exchanges? Absolutely, it may not be 100% present on their web site (here or here for example), but it is available to clients and qualified prospects. Is it readily available for crypto exchanges? No, not by a long stretch. Should it be? Well, in the absence of legal obligation, it is anybody’s call. One could argue however that disclosure goes a long way in establishing trust.

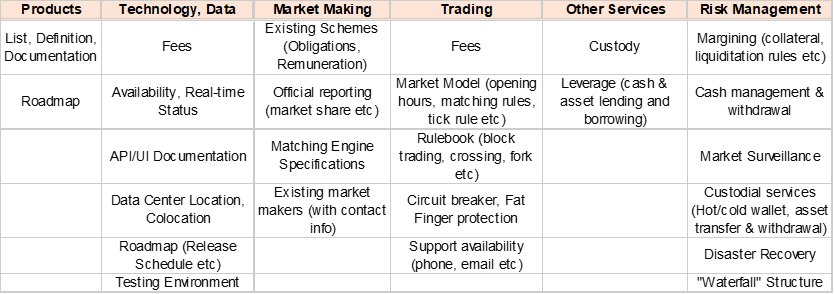

Next chapter, trading. Surely one needs to be well-informed about an exchange to be able to trade smartly. Like before, below is a non-exhaustive list of things you might want to know before transacting:

All in all, we are getting to the core of what an exchange is. There are very few cells in that table that are not highly relevant to the quality of service the exchange is able to deliver its clients. You might be tempted to consider some of those buckets are for professionals only, and that is indeed absolutely true. Then again, if professional traders conclude their due diligence favorably, chances are that any and all market participants will experience a higher quality of service.

Is that mass of information readily available from traditional exchanges? Absolutely, it may not be 100% present on their web site, but it is available to clients and qualified prospects. Is it readily available for crypto exchanges? No, not by a long stretch. Should it be? Insofar as it directly relates to the way orders, executions, risks are handled, there is little doubt here — it should be timely, accurate and exhaustive.