By Stéphane Reverre & Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

June 2023

Link to PDF version

Market Making Overview: TradFi vs Crypto – SUN ZU Lab

[NB: See the glossary at the end of the article for a definition of technical terms]

Liquidity(*) is the gasoline of any exchange, whether traditional or crypto, and the engines pumping it are called Market Makers. We define them in this article and go over their role, strategies, and risks, as well as a thorough comparison between market making in Tradfi and crypto.

We have already provided in-depth detail about TradFi and crypto market liquidity here, and why liquidity has become a question of survival for crypto venues here, so let us dive right into the nitty-gritty of market making.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com.

Market Making in TradFi

Historically, cash equity markets used to execute auctions manually to match buyers and sellers, and it could take seconds to fill a marketable order. Today, they are mainly electronic, with trading occurring on fully-automated exchanges and dark pools. In contrast, fixed Income markets remain primarily dealer-driven and over-the-counter (OTC)(*), in many cases still trading via person-to-person telephone interactions – although electronic trading is taking ground under regulatory pressure. Contrary to equities, foreign-exchange (FX) markets are dominated by a handful of the world’s largest banks and market-making firms, who stand ready to provide two-sided markets and liquidity even when central banks intervene, driving periods of high market volatility.

Registered market makers (MM)(*) generally provide transparent two-sided bid-ask(*) quotes at all times when a market is open, meaning that MMs will publish a price and amount that they are willing to buy or sell at throughout the trading session. In fact, Reg NMS(*) requires that registered MMs provide firm quotes immediately accessible to incoming orders. They are also usually constrained to maintain spreads below a maximum limit, a minimum order book depth and presence in the order book a minimum duration within trading sessions (the uptime requirement). As a result, MMs collect trading profits from their activity, in addition to incentives (for example, rebates against regular trading fees) offered for displaying orders at certain venues (from exchanges or issuers who want to maintain adequate liquidity). Liquidity providers are mostly passive in the order book, but they may occasionally aggressively take liquidity in some circumstances to manage their risk and inventory.

It is essential to note that MMs have a mandate to provide liquidity (i.e. help investors trade better), but absolutely not to move the price. This is achieved by keeping the MM obligation symmetric, with a bid AND ask price at the same time and a maximum spread to make sure MM prices are not too far from the actual price.

In the US, for example, the regulatory requirement is that the Designated Market Maker (DMM) must always be willing to buy or sell one round lot (usually 100 shares). They are further required to quote at the National Best Bid or Offer (NBBO) at least 15% (10%) of the trading day for securities trading over (under) 1,000,000 shares per day. When they are not at the NBBO, their quotes can be at most 8% away for stocks in the S&P 500 or Russell 1000 indexes. For other stocks, the maximum amount their quotes may be away from the NBBO is 28% for stocks trading at or over $1 and 30% otherwise. Market making obligations are only active during regular trading hours (9:30 AM – 4:00 PM) on most days: market makers are not required to quote outside these time frames.

On the European markets operated by NYSE/Euronext, there are two types of market makers – auction or permanent. The former add liquidity for stocks only traded through call auctions and the latter for stocks traded continuously. Auction market makers (also called “liquidity providers”, LP), are only required to maintain a spread during the order collection phase of each auction. The maximum spread width for both market makers is between 2% and 5% (€0.10 and €0.25) for stocks trading above (at or less than) €5. Euronext LPs obtain a reduction in fees and may receive side payments from the companies they trade. Such a payment occurs under a “liquidity contract”, under which a market maker receives a pre-agreed remuneration from the issuer to maintain a certain liquidity. Trading profits (and/or losses) are usually carried by the issuer (i.e. the market maker is insulated from market risk).

Market Making in TradFi overall is a heavily regulated and transparent business; regulators surveil MMs to ensure they comply with their obligations. Regulators (or exchanges) can impose both positive and negative obligations on market makers, requiring them to provide liquidity to the market or preventing them from executing a trade if a retail order could execute instead of it, for example. For example, EUREX (a European derivatives exchange) states here the specifics of Regulatory Market-Making, according to MiFID II, and Commercial Liquidity Provisioning on its platform. In practice, MMs sign a contract with exchanges, and the list and details of contractual MMs are public for everyone to see. The idea is that an investor looking for liquidity may directly contact a MM.

Market Making strategies, risks & examples

Here is an overview of the most common market making strategies in TradFi:

Delta Neutral Market Making: A market maker seeks to self-hedge against the inventory risk and wants to offload it in another trading venue. For that, a MM would place limit orders on an exchange with low liquidity, and when those are filled, immediately send a market order (on the opposite side) to an exchange with higher liquidity.

High-frequency “at touch” Market Making: A common strategy for MMs is submitting limit buy/sell orders at the best bid/ask prices. The MMs bid/ask order spread is then equal to that of the limit order book (LOB). Sometimes, MMs will submit orders at prices marginally higher than the bid and lower than the ask to gain order execution priority. However, this is only possible when spreads are not already very tight. Alternatively, a market maker could place their orders further into the LOB queue (lower bid and higher ask). This strategy produces higher margins but also a lower order execution rate.

Last Price: In this case, MMs will reference the last price a security traded at when placing their bid/ask quotes, submitting bid/ask orders one or two ticks away in either direction. This strategy provides a higher return than the “at touch”; however, this comes at the expense of higher end-of-day inventory of the given security.

Grid Market Making: In this case, a market maker places limit orders throughout the book, of increasing size, around a moving average of the price, and then leaves them there. The idea is that the price will ‘walk through’ the orders throughout the day, earning the spreads between buys and sells.

These strategies work well when prices are relatively stable but may lose money heavily during sustained momentum or volatility periods. When prices keep going up, the MM will find it extremely difficult to execute bid orders, accumulating an increasingly significant losing-money short position, and the same applies in the opposite direction. MMs should pay close attention to market volatility and order book imbalances to avoid being trapped in such situations.

According to studies published in 2014 and 2021, market makers are likely to reduce their market participation in periods of significant volatility. MMs often farther into the LOB in such situations to avoid being caught out by significant and abrupt changes in the market, reducing liquidity and potentially making markets even choppier. In addition to reduced trading volumes in periods of volatility, MMs will adjust their quoting price based on movements in the order book, monitoring the LOB for any order imbalances. For example, MMs will adjust their ask/bid quotes if the volume difference between bid and ask quotes grows, expecting an uptrend in price movements.

It is also interesting to note that when MMs operate under a contract with an exchange, they will often benefit from specific technical provisions: typically, the exchange will implement a “market maker protection” which essentially cancels all orders (at once) from a MM when violent price moves occur. There are also different modalities for order management (for example, a “bulk order” functionality, whereas regular investors can only send single orders, one at a time). Those features act as an incentive for MMs to stay in the market even when volatility rises (i.e. when they are most needed) by offering specific risk management tools.

All else equal, strategies accounting for order book imbalances increase returns and end-of-day inventory. Those adjusting the bid/ask quote for volatility will also increase returns while decreasing inventory. These two strategies are hence often combined to achieve optimal performance.

One of the most significant risks of market making is the inventory risk. MMs have to store a particular amount of assets to fill a buy/sell order, and the inventory risk manifests itself every time markets start forming a trend (upwards or downwards) for a sustainable period. The inventory risk in a scenario of decreasing prices results in the risk of having more of an asset at the wrong time, with difficulties to find buyers to unwind it. This risk is vastly larger in crypto markets, where prices are more volatile.

To illustrate the above, let us give a quick example of how a basic market-making trade takes place, a MM active on a stock X shows a bid and ask price with a quote of $10.00 – 10.05 (not necessarily the same bid and ask volumes). This means that the MM is willing to buy X stocks for $10.00 and sell them at $10.05, earning a spread of 5 cents per share (in the absence of market movement, this is indeed a maximum gain). If everything goes well, the MM could buy and sell 10,000 shares at these quotes, earning $500 from this trade.

If, on the contrary, a large sell order takes place, the MM could find itself long Y shares with the best ask down to $99.95, for example. The MM is faced with the choice to hold its position if it believes prices will reverse higher, post an order to sell at $99.95, or even choose to simply trade out of the position by selling to the prevailing highest-priced buy order, locking in a trading loss.

Crypto Market Making

The market making business in the crypto space has little to do with its older, more established counterpart in TradFi. After 14 years, crypto markets are still in a “far west” state. It is not an exaggeration to say that exchanges are far from mature, from both a technical and regulatory standpoint: liquidity is low (to very low), highly concentrated on a few instruments, slippage risks are high, manipulation is frequent, and there are clear probabilities of flash crashes when large orders appear.

Market Making agreements in crypto are also different from TradFi in many aspects, mainly:

- High engagement fees: Market makers with an established name may require payments as high as $100,000 for setup fees, $20,000 monthly fees, and a $1 million BTC and ETH loan.

- Asymmetry in pay structure: The use of options (see below) creates a situation where MMs have an incentive to manipulate the price of the token. This is absolutely illegal in TradFi.

- Imbalanced deals: Token issuers had historically little negotiation room with MMs due to the uncertainty around traded volumes after listing, leading to deals mainly favoring MMs. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem: no MM means little liquidity and little liquidity means little negotiating power vis-à-vis MMs demands.

- Little to no measurement or performance: token issuers are tech-savvy but often have insufficient financial knowledge to assess actual MMs impact on liquidity. In contrast, TradFi exchanges produce quantitative assessments of liquidity provisions, and can end liquidity contracts for insufficient performance or poor compliance with stated KPIs.

- Bad actors: Crypto’s lack of regulation has attracted all sorts of fraudulent players that engage in deceptive activities such as wash trading, spoofing, or misuse of token loans.

The terms of the market-making agreement, also known as the Liquidity Consulting Agreement (LCA), often evolve around compensation: MMs will receive financial incentives to reward improvements in a token’s liquidity and market value. Typical components are service fees, options, or KPI-based fees:

- Service fees: They usually involve initial setup fees to the MM at the beginning of the agreement, recurring (monthly or quarterly) retainer fees, or no fees in times of raging bull markets when hyped tokens become profitable enough for MMs to trade (without any other sort of compensation).

- Call Options: They provide the MM with financial upside when the token’s price rises, incentivizing them to try and keep the price above a specific strike price. The use of options aligns the founders’ interests with the MM’s, but at the expense of a fair and efficient market because of the embedded incentive to artificially manipulate the token’s price. This was particularly common in bull markets when the frenzy for new tokens pushed MMs to negotiate options in their package. Due to MMs’ vastly superior financial expertise compared to token founders, using options in a MM deal is the perfect opportunity to leverage the information asymmetry and increase the MM’s value creation on the back of the token community. The use of call options is utterly absent from TradFi because it creates an incentive to manipulate the price and pump it up.

- Performance-based fees: These fees can be paid if certain thresholds are reached (volume, price, spread…). Such fee agreements are dangerous to implement as they can (also) encourage malpractices like wash trading.

- Token Loans: MMs cannot sell what they do not own. To show ask prices and sell tokens, they have access to a reserve of tokens. That reserve is usually provided free of charge by the token ecosystem from the token pool issued but not yet available to the public. There is naturally the risk that MMs cannot return the tokens and that risk should naturally be explicitly covered in the agreement.

Examples of such crypto market making agreements are public and can be found here or here.

Crypto markets also bring the question of CEXs vs DEXs market making. Market making on centralized exchanges is similar in principle to what professional firms do in Tradfi. Another critical concept is the difference between “maker” and “taker” orders. The former refers to orders where the buyer or the seller defines a price limit at which they are willing to buy or sell. Taker orders, by contrast, are orders that are executed immediately at the best bid or offer. Thus, maker orders add liquidity, and taker orders remove it. Crypto market makers must be meticulous when managing their inventory to not pay excessive taker fees (example of the fee structure on Coinbase).

Regarding market making on DEXs, we previously highlighted the process of price discovery in DeFi protocols, taking the example of liquidity pools in Automated Market Makers (AMMs) with a focus on Uniswap (qualitative and quantitative analysis).

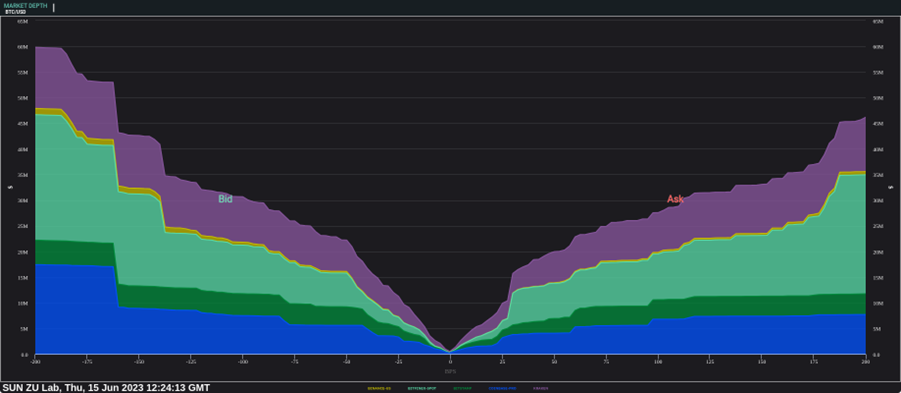

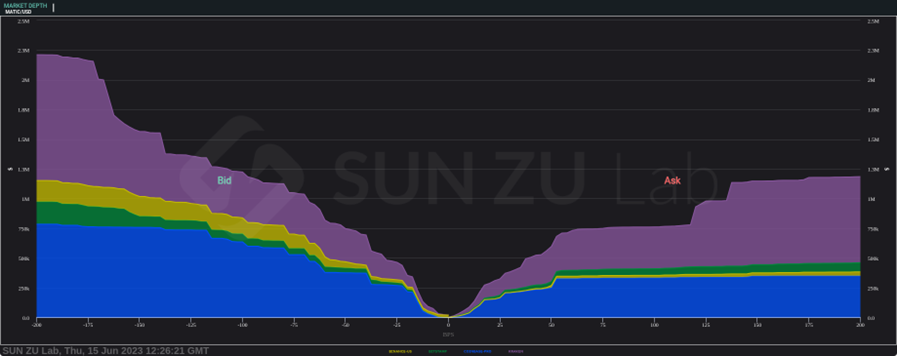

Market depth comparison between BTC/USD (~$60m/$45m bid/ask volume at 200 bps) and MATIC/USD (~$2.3m/$1.3m bid/ask volume at 200 bps), on Binance.Us, Bitstamp, Coinbase-Pro, Kraken and Bitfinex

Source: SUN ZU Lab Live Dashboard

Glossary:

- Market Maker (MM): The SEC defines a market maker as “a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock at public quoted prices.” A market maker (MM) is a professional trader who actively quotes two-sided markets in a particular asset, providing bids and asks for a pre-defined quantity.

- Alternative Trading Systems (ATS): also known as dark pools, are private marketplaces where investors place buy and sell orders without the venue disclosing its order book (i.e. available prices or volumes it has received from investors).

- Bid: The highest price a buyer is willing to pay to purchase a security or financial instrument. It represents the demand side of the market, and market makers provide bid prices at which they are willing to buy securities from potential sellers.

- Ask: The lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell a security or financial instrument. It represents the market’s supply side, and market makers provide ask prices at which they are willing to sell securities to potential buyers.

- Bid/Ask Spread: The difference between the highest price (bid) a market maker is willing to pay for a security or financial instrument and the lowest price (ask) at which they are willing to sell. From an investor viewpoint, the spread represents the cost of trading while it can be seen as a (maximum) profit margin for market makers.

- (Market) Liquidity: is defined as the ability to buy or sell large quantities of an asset without significant adverse price movement.

- Market Depth: The measure of the quantity of buy and sell orders at different price levels for a security or financial instrument. Market makers closely monitor the market depth to assess supply and demand dynamics, adjust their bid and ask prices accordingly.

- Order Book: A digital record of all outstanding buy and sell orders for a security or financial instrument, organized by price level. Market makers use the order book to gauge market sentiment and make pricing decisions.

- OTC (“over the counter”): refers to a type of trading where parties negotiate terms privately. It is opposed to an “organized market” where trading is governed by standardized instruments and rules, and trading is often anonymous.

- Quote: A market maker’s bid and ask prices for a security or financial instrument. Quotes are typically displayed on electronic trading platforms and reflect the market maker’s willingness to buy or sell at those prices (for a given quantity).

- Arbitrage: The practice of taking advantage of price discrepancies in different markets or instruments to make a risk-free profit. Market makers may use arbitrage strategies to capture slight price differences between trading venues or related securities.

- Regulation National Market System (Reg NMS): a set of rules passed in 2005 by the SEC that sought to refine how all listed US stocks are traded. The intention was to boost transparency by improving the displaying of quotes and access to market data and ensuring that investors get the best price on their orders.

- Regulation of Exchanges and Alternative Trading Systems (Reg ATS): became effective in 1999 and was set by the SEC to regulate trading activities on ATS.

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.