This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

SUN ZU Lab & OKX: Our first Exchange Liquidity Analysis report

By Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

April 2024

We are proud to announce that OKX has partnered with SUN ZU Lab to bring you their first Exchange Liquidity Analysis report. This report focuses on OKX spot and perpetual futures liquidity, providing valuable insights to navigate the dynamic landscape of trading on OKX.

“During this period, the crypto market experienced a significant upswing, and OKX showed considerable trading volume and healthy order books in February 2024”, according to the analysis by SUN ZU Lab.

Link to the official announcement!

Download full report to uncover more insights

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com.

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides Token Issuers & Market Makers with institutional standard actionable data solutions to improve the transparency and fairness of Crypto markets.

The Complete Web3 Ecosystem Mapping

By Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

April 2024

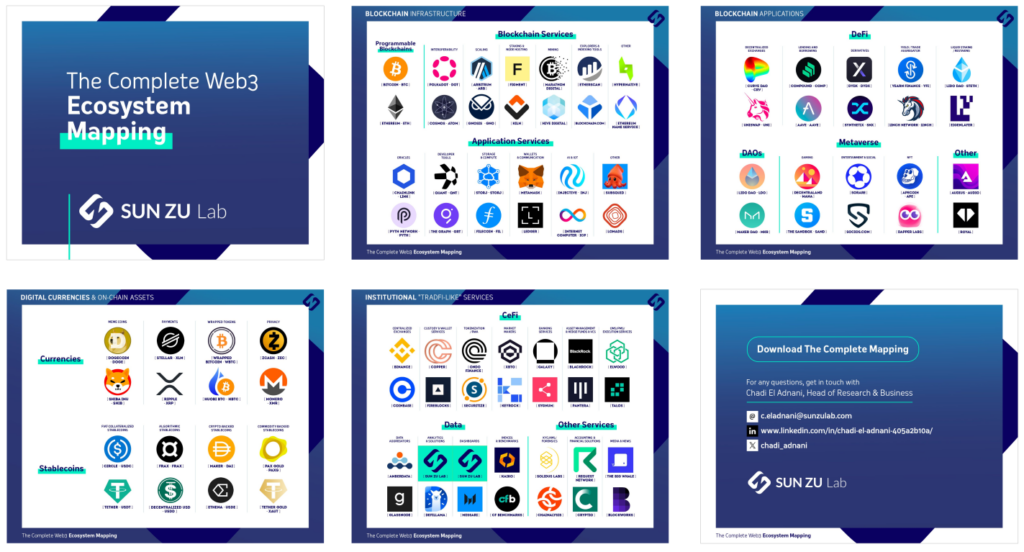

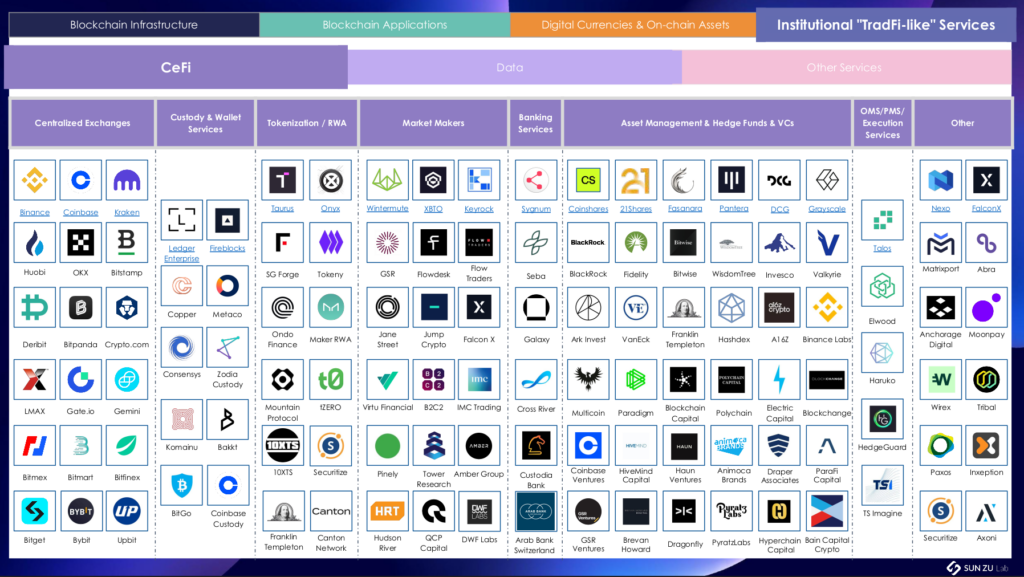

We publish today the results of our (almost) Complete Mapping of The Web3 Ecosystem, after months of research and screening the market.

With a total of more than 500 companies/projects listed, we cover the bulk of the ecosystem in terms of the relevant metrics in each category: Market cap, TVL, AUM, fees, volumes, revenue, user adoption…

The mapping’s structure is inspired by some established industry segmentations (e.g., CeFi vs. DeFi, fiat-backed stablecoins vs. crypto-backed stablecoins, on-chain vs. off-chain…), as well as our own understanding and interactions with the ecosystem’s key players.

A total of 4 high-level categories: Blockchain Infrastructure; Blockchain Applications; Digital Currencies & On-chain Assets; Institutional “TradFi-like” Services, divided into sub-categories (e.g., Blockchain Infrastructure > Blockchain Services) and further down into sub-sub-categories (e.g., Blockchain Applications > DeFi > Decentralized Exchanges)

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com.

Link to the Complete Mapping

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides Token Issuers & Market Makers with institutional standard actionable data solutions to improve the transparency and fairness of Crypto markets.

Market Making: Guidebook to Crypto Foundations & Token Issuers

By Stéphane Reverre & Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

February 2024

[NB: See the glossary at the end of the article for a definition of technical terms]

Liquidity(*) is the gasoline of any exchange, whether traditional or crypto, and the engines pumping it are called Market Makers. We have provided in a previous article a rather technical view on the subject. Today’s approach targets a broader non-technical, non-financial audience, with a focus on token foundations and issuers.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com.

What is Market Making (MM)? The case of the used car market:

Say you are looking for a car, and quite naturally, end up at your local dealership. Under normal circumstances, the salesman can offer a brand-new vehicle, or a used one. Those prices are “offered” prices: the salesperson is selling/you are buying.

Done deal: you get a used car, but unfortunately, realize 5 months later that it really doesn’t do the job. Too small, too big, whatever it is, you go back to the salesperson: “Hello, I bought a car from you 5 months ago, and it is not quite what I need. Can I sell it back?”. At this point, you may receive two different answers:

i/ “Sorry, I don’t have a buyer; let me call you back when I do.” In that case, you will be able to sell when a buyer comes along, not before. You may also look for a buyer yourself.

ii/ “Yes, of course, I’ll take it from your hands at …”. This price is a bid price i.e., the dealership is buying/you are selling.

The bid price will be lower than the original offer for obvious reasons (you drove the car for 5 months). Now, let’s assume, for the sake of the discussion, that you go back the day after your purchase. Will the salesperson bid the same price they offered the day before? Probably not. A bid will be lower than the offer price, if it is forthcoming.

The difference between bid and offer (also called the “ask” or “asking” price) is called the “spread”(*). In practice, this is the minimum profit margin the dealership will want to secure to offer the used car service. This margin exists for a number of reasons, but most notably because the dealership is taking a financial risk in carrying an inventory of used cars. Bottom line: the bid-offer spread is necessary to remunerate a risk. This is why even if you bring the car the next day, you will not get the offer price: the dealer takes a risk by accepting the car back, and a profit will be needed to pay for that risk.

Market Making in Finance:

The SEC defines a market maker as “a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock at public quoted prices.” A market maker (MM) is a professional trader who actively quotes two-sided markets in a particular asset, providing Bids(*) and Asks(*) for a given quantity.

There is, in practice, no difference between a financial MM and a car dealership (no kidding). The difference is in the asset: contrary to cars, stocks are fungible (i.e., perfectly identical for a given issuer), not subject to wear and tear, and not continuously produced, which means that the “second hand” market is very active (you cannot get a “brand new” share).

A car dealership will always provide an offer price for a new car because it is its primary business, the one from which it derives most of its revenues. The fact that it would provide a bid price for a used car depends on a number of factors, and no dealership will consider that it has an obligation to do so. To be clear, selling new cars doesn’t create a financial risk: the dealership takes a deposit, orders the car, and delivers it against payment when the manufacturer has shipped. Buying a used car means getting cash out, with the risk of getting stuck with a car that nobody wants.

Like the dealership, a MM may choose to participate in the market at all times or not, buying assets from sellers and selling them to buyers. MMs’ primary mandate is to provide liquidity, which ensures investors can trade quickly and at a fair price in all conditions. This creates a win-win situation where the MM earns profits for its services, and the overall market enjoys a certain level of liquidity, price stability and confidence. Evidently, MMs that decide to participate at all times carry a larger financial risk than those that do not. For a dealership, the level of financial risk is captured by the inventory of used cars waiting to be sold. This is exactly the same thing for the financial MMs.

It is essential to note that MMs have a mandate to provide liquidity (i.e. help investors trade better), but not to move the price. This is achieved by keeping MM obligations symmetric, with a bid AND offer price published simultaneously and a maximum spread, in all market conditions. Obviously, if a MM is stuck with too much inventory, its risk management may push for liquidation, which in turn may impact the asset price. However, this impact is not a primary result of the MM intervention; it is a consequence of adverse risk conditions (even if the risk results from poor management). Ideally, a car dealership will want to buy and sell used cars so quickly that its inventory remains near zero as often as possible. It’s the same thing for a financial MM: trading is rapid on both sides of the spread, and inventory is null at the end of every day.

In real life, two situations occur: extremely liquid assets/tokens that can be easily bought or sold without causing significant price impact, and less liquid assets/tokens that experience substantial price swings every time a sizeable trade is executed. MMs are extremely useful in the second case.

Liquid asset: BTC-USDT on Bitstamp

Source: SUN ZU Lab Live Monitoring Dashboard

Let’s take Bitcoin (BTC) as an example of a very liquid asset. The lowest number in red represents the best Ask/Offer (the lowest price at which sellers are willing to sell, on this specific exchange, at the moment). In contrast, the highest number in green represents the best Bid (the highest price buyers are willing to offer for Bitcoin), the difference between the two is the Bid-Ask spread (4 USDT or 0.916 bps). We can see on the last column (cumulative $ USDT sell/buy order amounts at each level) that a $11K (USDT) spot buy order would leave the best Ask at 43,671 USDT, moving the mid-price by a mere 3 USDT to 43,676, and the new spread to 10 USDT or 2.3 bps. This would be a temporary situation as market participants would move quickly to fill this gap and bring the spread back to previous levels.

Illiquid asset: POLIS-EUR on Kraken

Source: SUN ZU Lab Live Monitoring Dashboard

In the case of POLIS-EUR as an example of an illiquid asset, a €1000 sell order would move the best Bid down to €0.301, creating a €0.027 spread, or a whopping 8.6%!

The business of Market Making:

In TradFi, there are situations where market-making is voluntary and optional, and others in which it is self-imposed or even constrained by a contract. There are, for example, many hedge funds running “statistical arbitrage” strategies that are akin to voluntary market-making. The strategy stands ready to buy and sell in the market with a certain spread, and doing so will (hopefully) generate trading profits without too big an inventory. But if you want to become a registered MM with certain privileges, you must commit to continuously quoting prices. Examples of that abound in Europe; most electronic exchanges have MM programs for specific products: in exchange for a commitment to provide liquidity, MMs will enjoy reduced fees or sometimes outright payments. Under those commitments, MMs must quote a minimum volume at a maximum spread, and stick to those parameters at all times and during all market regimes.

When MMs operate under a contract with an exchange, they will often benefit from specific technical provisions: typically, the exchange will implement a “market maker protection,” which essentially cancels all orders (at once) from a MM when violent price moves occur. There are also different modalities for order management (for example, a “bulk order” capability, whereas regular investors can only send single orders, one at a time). Those features incentivize MMs to stay in the market even when volatility rises (i.e., when they are most needed) by offering privileged risk management tools.

As an industry, market makers earn the ‘spread’ between bid and ask prices because they accept to carry inventory risk. When the spread is contractually set, their profit margin is mechanically constrained.

In today’s highly competitive markets, the bid-ask spread is often razor thin (0.1 to 1 bp for Bitcoin on leading centralized exchanges). To remain profitable, a market maker must price assets quickly and accurately, be able to execute trades at scale, and manage its inventory properly.

Inventory risk is indeed the most important risk here. You have to have some to fulfill your obligations (what if a buyer comes asking for some?), and yet it is subject to price movements. Too much of it will cost if prices are going down, and too little may prevent you from fulfilling investors’ demands. Incidentally, this risk is even more pronounced in crypto markets, where prices are more volatile.

The Importance of Market Making:

Liquidity & Depth

Market makers make it easier for investors to buy or sell an asset quickly or in large volumes. In financial terms, they deliver liquidity and depth to the market.

Attracting and concentrating the asset’s tangible volume is crucial – as opposed to engaging in practices like wash trading (*), layering or spoofing(*), which attempt to create fake or misleading volume. This distinction is significant in maintaining ethical financial practices and building investors’ trust. Market makers play a vital role in this, as their ability to optimize liquidity directly impacts the organic volume and, in the end, investors’ confidence.

Insuring New Token Launch Success

New tokens are usually not widely known after their initial listing on exchanges and may suffer from a limited community of buyers and sellers, making it challenging for market participants to find each other and agree on a price. This is where MMs are extremely important to tighten the spreads, buying from sellers and selling to buyers at prices they both deem fair and acceptable. We covered in a previous article how the Worldcoin team relied on five MMs during the launch phase to ensure “sufficient liquidity for WLD traded on centralized exchanges outside the US, to facilitate price discovery, and to enhance price stability of WLD.”

Greater Price Stability and Lower Volatility

Market makers’ presence streamlines the execution of trades, reduces fluctuations in prices, and dampens supply and demand gaps. These activities build confidence among market participants. Market makers help ensure that markets function reliably and remain resilient even during times of turbulence.

Enforcing Price Coherence across Venues and Products

Crypto market makers can play a role in mitigating price discrepancies between different exchanges or instruments. They continuously quote buy and sell prices across different venues and related instruments, thereby strengthening market integration.

How to choose your crypto Market Maker:

Because of their role in providing liquidity, MMs have an important role to play in the crypto ecosystem. Yet, bulletproof standards have not found their way into the marketplace, and stakeholders are not necessarily well protected – without even being aware of it. When choosing a MM to contract with, the most important questions are often those that are not even on the table. You know, the old adage: “What should I ask that you are not telling me?”

Here are, in our views, a few important considerations and certainly questions for which you should be getting answers – or your money back:

- Consistent spreads & deep order books: “How do I know that you are in the market when you are needed and at the very least when you are supposed to?”. We view this as the single most important question a MM should answer. There are four fundamental characteristics of a well-formed MM contract: size, spread, time, and symmetry. A professional MM will provide prices for a given symmetric size and maximum spread with a minimum presence (say 90% of the time, measured with 12- or 24-hour intervals). Token issuers often do not have the financial knowledge to assess MMs’ actual impact on liquidity. MMs provide reporting on their activity, but isn’t that the left hand evaluating the right one? An independent assessment is the best way to go, and any serious MM will agree and diligently accept third-party assessment of contractual KPIs. Today, few actors in crypto are able to provide transparency on whether Market Makers are actually doing their job – SUN ZU Lab was created to answer that question.

- Risk management: “How do you manage your inventory?” MMs have full latitude to manage their risk as they see fit, but accumulating undue inventory may create tremendous selling pressure if liquidation occurs suddenly. In fact, it’s a double whammy: if a sharp fall in price forces a MM to liquidate a sizeable inventory, it will only add to the overall sentiment of panic. Best practice suggests an inventory risk under control and within reasonable limits (whatever they are). As a token issuer, you don’t care about MMs inventories, but certainly, you care about the possibility of a massive downward shock if those inventories accumulate too much or too fast.

- Reputation and business ethics: “How do I know that you will not engage in manipulation or other deceptive practice at the expense of token holders?” Well, crypto being unregulated, MMs can do on the side whatever they want. But at the very least the issue of reputation and fairness should be put on the table, and commitments should be made.

- Profitability: “How much trading profit do you make?” This one is a hard transparency question, and not all MMs may want to answer. Being constrained, a MM may not always make a trading profit. On average though, trading profit plus contractual remuneration should add up and be positive. Yet, too much profit means that the contract is unbalanced.

Glossary:

- Market Maker (MM): The SEC defines a market maker as “a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock at public quoted prices.” A market maker (MM) is a professional trader who actively quotes two-sided markets in a particular asset, providing bids and asks for a pre-defined quantity.

- Bid: The highest price a buyer is willing to pay to purchase a security or financial instrument. It represents the demand side of the market, and market makers provide bid prices at which they are willing to buy securities from potential sellers.

- Ask: The lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell a security or financial instrument. It represents the market’s supply side, and market makers provide ask prices at which they are willing to sell securities to potential buyers.

- Bid/Ask Spread: The difference between the highest price (bid) a market maker is willing to pay for a security or financial instrument and the lowest price (ask) at which they are willing to sell. From an investor viewpoint, the spread represents the cost of trading while it can be seen as a (maximum) profit margin for market makers.

- (Market) Liquidity: Is defined as the ability to buy or sell large quantities of an asset without significant adverse price movement.

- Market Depth: The measure of the quantity of buy and sell orders at different price levels for a security or financial instrument. Market makers closely monitor the market depth to assess supply and demand dynamics, adjust their bid and ask prices accordingly.

- Order Book: A digital record of all outstanding buy and sell orders for a security or financial instrument, organized by price level. Market makers use the order book to gauge market sentiment and make pricing decisions.

- OTC (“over the counter”): refers to a type of trading where parties negotiate terms privately. It is opposed to an “organized market” where trading is governed by standardized instruments and rules, and trading is often anonymous.

- Quote: A market maker’s bid and ask prices for a security or financial instrument. Quotes are typically displayed on electronic trading platforms and reflect the market maker’s willingness to buy or sell at those prices (for a given quantity).

- Arbitrage: The practice of taking advantage of price discrepancies in different markets or instruments to make a risk-free profit. Market makers may use arbitrage strategies to capture slight price differences between trading venues or related securities.

- Wash trading: A form of market manipulation in which an entity simultaneously sells and buys the same financial instruments, creating a false impression of market activity without incurring market risk or changing the entity’s market position.

- Spoofing: A term used to describe a form of market manipulation where traders place a Bid or Ask order with no intention of fulfilling it, instead canceling it before execution, with the sole intention of manipulating markets in a certain direction (up or down).

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides Token Issuers & Market Makers with institutional standard actionable data solutions to improve the transparency and fairness of Crypto markets.

Why will at least 80% of centralized crypto exchanges (CEXs) disappear?

By Stéphane Reverre & Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

August 2023

TL;DR

- History in TradFi shows concentration is inevitable. It is objectively not in investors’ interest to have such a high level of fragmentation among crypto trading venues;

- Liquidity attracts liquidity! losers will die a slow death;

- Regulatory pressure will (also) determine who lives and who dies;

- The race to zero on trading fees is already here.

It was October 2022 when we published an article titled “Why has liquidity become a question of survival for crypto venues?” urging centralized crypto exchanges to consider liquidity as the “gold standard” of their future profitability and deploy all necessary resources to monitor it and understand its drivers. Little did we know that one month later, the FTX/Alameda implosion would put the entire crypto ecosystem, and mostly centralized exchanges, on the brink of collapse.

Halfway through 2023, CEXs’ order book depths and trading volumes are ~10x thinner on average than 2022 levels, prompting us to express an even more aggressive view: “Why at least 80% of centralized crypto exchanges (CEXs) are going to disappear?” Liquidity attracts more liquidity in the same way success is a magnet for even more triumphs. Add to that the looming regulatory pressure, and the bottom majority of CEXs will start falling like a domino chain, with the losers dying slowly.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com

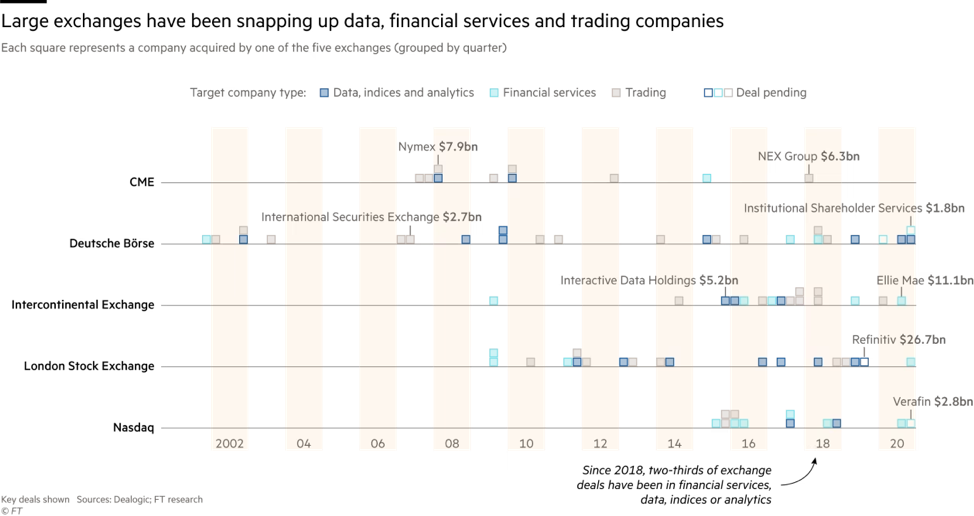

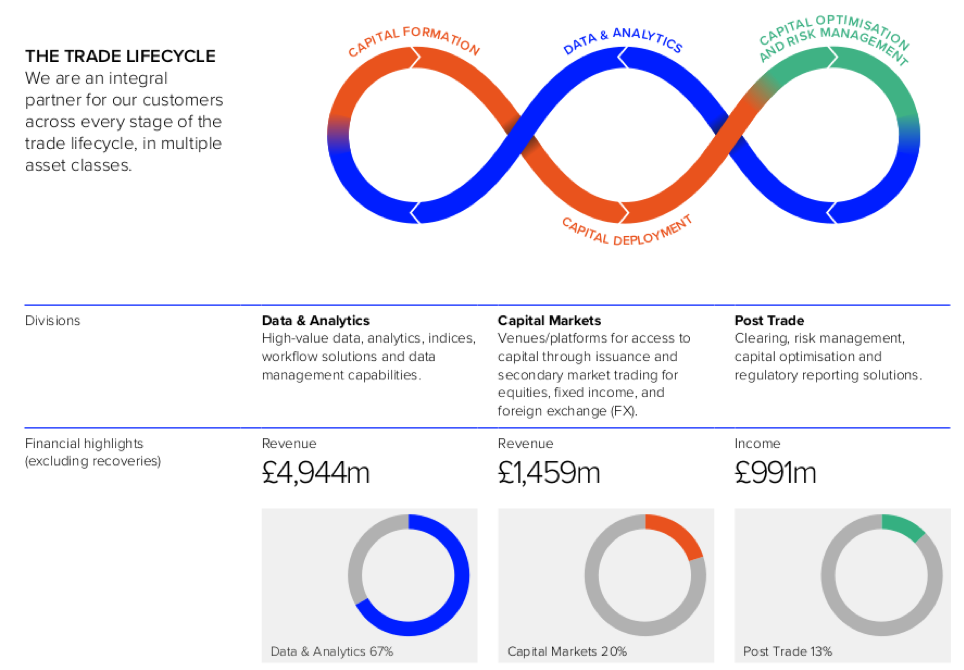

In TradFi, capital markets have been all about scale. Whether in banking, asset management, hedge fund, or trading venues sectors, the bigger are getting bigger! M&A has been one of the most significant value drivers for TradFi exchanges over the last 20 years, allowing groups to generate significant economies of scale by mutualizing costs from data centers, matching engines, and employees. Here is a selected list of the major acquisitions of the century:

- NYSE merged with Archipelago Holdings (2006, $9 bn), creating the NYSE Group;

- NYSE Group and Euronext merged (2007, $10 bn) to form NYSE Euronext;

- Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) acquired NYSE Euronext (2013, $11 bn); Euronext spun off from ICE in a $1.2 bn IPO in 2014;

- Euronext acquired Borsa Italiana from the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) (2021, $5 bn).

Even though it is not exactly the same industry, The FDIC’s website provides additional valuable information on the evolution of the banking industry in the US. Between 1990 and 2022, the number of commercial banks insured with the FDIC went from 12,347 to 4,136, with the number of newly issued charters virtually near zero since 2008. As the retail and corporate segments increased significantly over the same period, the major remaining banks enjoyed the full benefits of consolidation and economies of scale with minimal efforts!

The list of exchanges’ failed M&A deals is even longer:

- Deutsche Boerse offered $1.6 bn for LSE before withdrawing its proposition in 2005;

- LSE rejected a $4 bn offer from Nasdaq in 2007;

- A merger between NYSE Euronext and Deutsche Borse failed in 2011;

- A merger between LSE and TMX Group died in 2011;

- Singapore Exchange terminated its $8 bn bid for Australia’s ASX after the Australian government formally rejected the offer;

- An attempted merger between Deutsche Boerse and the LSE was struck down by EU regulators in 2017;

- Hong Kong exchange dropped its $39 bn bid to buy the LSE in 2019.

The remaining big five exchanges have also gone on an acquisition spree for data, analytics, indices, execution, settlement, and other infrastructure providers, as can be seen in the graph below, with the crown going to LSEG for its $27 bn acquisition of data and trading group Refinitiv, approved by EU regulators in 2021.

Overall, the exchange business in Tradfi has seen many agitations up to the 2000s. This was followed by an accelerated consolidation wave, leading to the current market state post-2008’s GFC (“Global Financial Crisis”), where there is virtually no room for another newcomer due to the heavy regulation and high cost of capital (unless through an acquisition). The exact cause having the same effects, we expect the same level of consolidation to happen over the next couple of years for centralized crypto exchanges. This trend should be accelerated with the recent rise of “institutional” crypto trading venues, the latest being the launch of EDX Markets, backed by Citadel Securities, Charles Schwab, & Fidelity. EDX will operate as a non-custodial exchange, serving only institutional clients with plans to launch EDX Clearing to settle trades matched on the exchange, a feature still absent from nearly all CEXs.

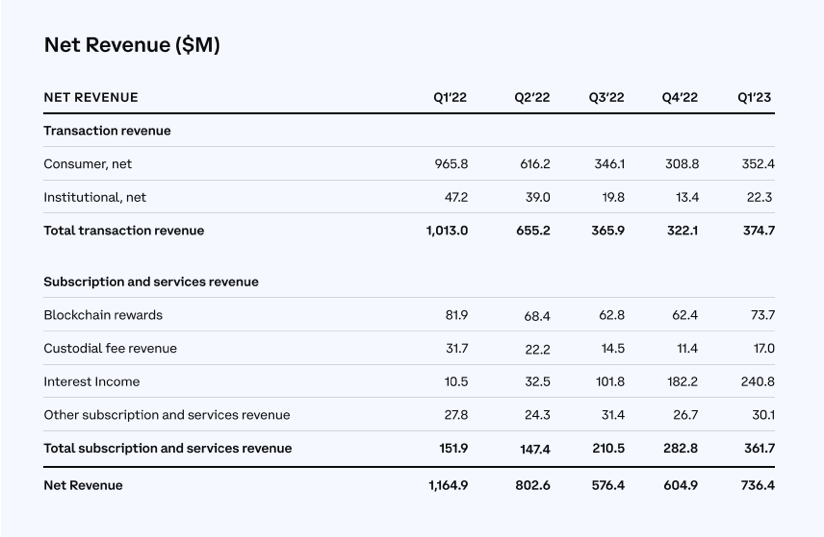

Coinbase, the first crypto exchange to go public, provides us with a valuable sneak peek into its financials through regulatory filings:

We can notice that, disregarding a slight uptick in Q1 23, transaction revenues have been free-falling since 2022, with total revenues divided by three over the period. However, revenues from subscriptions and other services more than doubled to $362 million. The compensation from diversification channels wasn’t enough to compensate for the loss from transaction revenues, as Net Revenue fell 37% YoY. Coinbase also introduced in May 2023 a new subscription service called “Coinbase One,” available for a monthly fee of $29.99 and providing a range of features that include zero trading fees, increased staking rewards, and round-the-clock customer support. The service was launched in the US, UK, Ireland, and Germany, with plans to extend its availability to 35 countries. Coinbase’s race and doubling down on revenue diversification is a strong distress signal for all other centralized crypto exchanges, which we are sure are in a far worse state than the leader Coinbase.

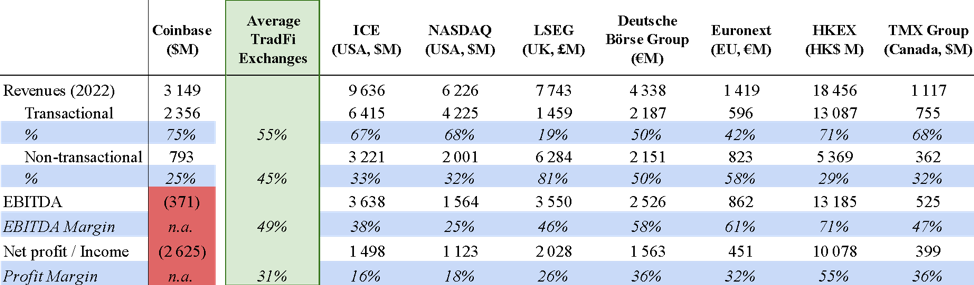

To put matters into perspective, here is a financial performance comparison in 2022 between Coinbase and the major TradFi exchanges around the world:

The proportion of non-transactional revenues for TradFi exchanges (45% on average) is way higher than Coinbase’s figure. TradFi exchanges are also impressive cash cows, with an average EBITDA margin of 49% and an average profit margin of 31%. The fact that the leader of crypto centralized exchanges is nowhere near these profitability levels is one major alarming sign for the whole sector. The only path to recovery is through revenue diversification, and one surprisingly unexplored gold mine is data monetization!

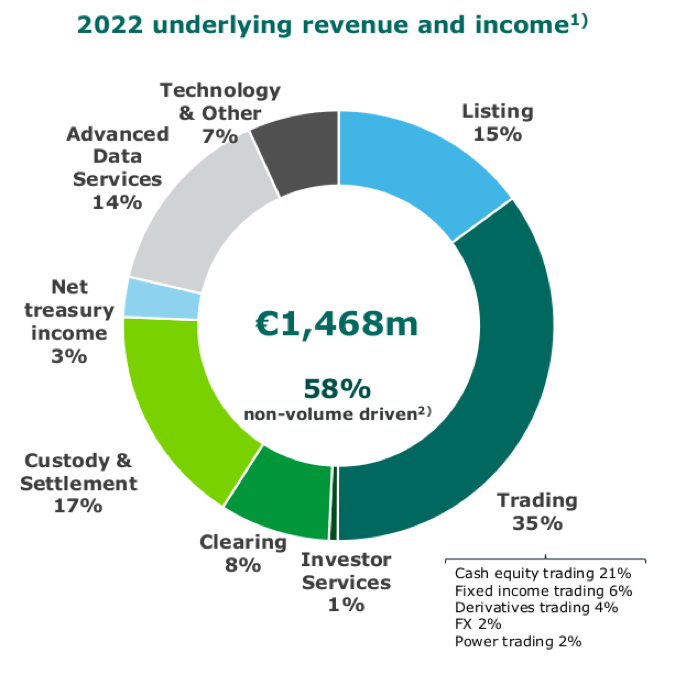

Below are two examples of how Euronext and LSEG diversify their revenue streams:

Centralized crypto venues should realize the magnitude of the problem and face the fact: if the market leader still hasn’t found a magic formula to profitability, maybe the solution isn’t different from what has been a major success in TradFi for years!

The path to recovery and survival, in our view, starts with asking the right questions:

- Do you know your client base?

- Do you know your liquidity patterns and those of your competitors?

- Do you know the strength and limits of your technology?

- Do you do what it takes to improve the quality of your data and monetize it?

A thorough internal process revue around the previous questions should give the first movers among CEXs the opportunity to:

- Adapt your marketing efforts to attract investors according to their trading patterns (retail, institutional, high frequency, etc.);

- Adapt your commission schedule to your clients’ trading patterns;

- Attract the structure and mandate of market makers on your platform;

- Diversify revenue: one natural resource still not explored by many CEXs is to make your market data valuable and find the business model to monetize it;

- Anticipate regulators’ questions about governance and manipulation;

- Position for industry concentration, as an acquirer or as a target. The few exchanges that make it through this harsh consolidation period will be profitable beyond their wildest dreams, but you must take action today!

We have been connected to 40+ major centralized crypto exchanges at SUN ZU Lab for years. Our cutting-edge technology and deep market microstructure expertise provide us with a sharp view of tick-level order book activity in these exchanges, most often giving us a better understanding of their trading dynamics than management teams lacking internal resources. We have the right combination to accompany a centralized crypto venue to answer the previous problems before it is too late!

Let’s discuss

About SUN ZU Lab:

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring better data to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards, API streams, and historical files. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market.

Market Making Overview: TradFi vs Crypto

By Stéphane Reverre & Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

June 2023

Link to PDF version

Market Making Overview: TradFi vs Crypto – SUN ZU Lab

[NB: See the glossary at the end of the article for a definition of technical terms]

Liquidity(*) is the gasoline of any exchange, whether traditional or crypto, and the engines pumping it are called Market Makers. We define them in this article and go over their role, strategies, and risks, as well as a thorough comparison between market making in Tradfi and crypto.

We have already provided in-depth detail about TradFi and crypto market liquidity here, and why liquidity has become a question of survival for crypto venues here, so let us dive right into the nitty-gritty of market making.

Questions and comments can be addressed to c.eladnani@sunzulab.com or research@sunzulab.com.

Market Making in TradFi

Historically, cash equity markets used to execute auctions manually to match buyers and sellers, and it could take seconds to fill a marketable order. Today, they are mainly electronic, with trading occurring on fully-automated exchanges and dark pools. In contrast, fixed Income markets remain primarily dealer-driven and over-the-counter (OTC)(*), in many cases still trading via person-to-person telephone interactions – although electronic trading is taking ground under regulatory pressure. Contrary to equities, foreign-exchange (FX) markets are dominated by a handful of the world’s largest banks and market-making firms, who stand ready to provide two-sided markets and liquidity even when central banks intervene, driving periods of high market volatility.

Registered market makers (MM)(*) generally provide transparent two-sided bid-ask(*) quotes at all times when a market is open, meaning that MMs will publish a price and amount that they are willing to buy or sell at throughout the trading session. In fact, Reg NMS(*) requires that registered MMs provide firm quotes immediately accessible to incoming orders. They are also usually constrained to maintain spreads below a maximum limit, a minimum order book depth and presence in the order book a minimum duration within trading sessions (the uptime requirement). As a result, MMs collect trading profits from their activity, in addition to incentives (for example, rebates against regular trading fees) offered for displaying orders at certain venues (from exchanges or issuers who want to maintain adequate liquidity). Liquidity providers are mostly passive in the order book, but they may occasionally aggressively take liquidity in some circumstances to manage their risk and inventory.

It is essential to note that MMs have a mandate to provide liquidity (i.e. help investors trade better), but absolutely not to move the price. This is achieved by keeping the MM obligation symmetric, with a bid AND ask price at the same time and a maximum spread to make sure MM prices are not too far from the actual price.

In the US, for example, the regulatory requirement is that the Designated Market Maker (DMM) must always be willing to buy or sell one round lot (usually 100 shares). They are further required to quote at the National Best Bid or Offer (NBBO) at least 15% (10%) of the trading day for securities trading over (under) 1,000,000 shares per day. When they are not at the NBBO, their quotes can be at most 8% away for stocks in the S&P 500 or Russell 1000 indexes. For other stocks, the maximum amount their quotes may be away from the NBBO is 28% for stocks trading at or over $1 and 30% otherwise. Market making obligations are only active during regular trading hours (9:30 AM – 4:00 PM) on most days: market makers are not required to quote outside these time frames.

On the European markets operated by NYSE/Euronext, there are two types of market makers – auction or permanent. The former add liquidity for stocks only traded through call auctions and the latter for stocks traded continuously. Auction market makers (also called “liquidity providers”, LP), are only required to maintain a spread during the order collection phase of each auction. The maximum spread width for both market makers is between 2% and 5% (€0.10 and €0.25) for stocks trading above (at or less than) €5. Euronext LPs obtain a reduction in fees and may receive side payments from the companies they trade. Such a payment occurs under a “liquidity contract”, under which a market maker receives a pre-agreed remuneration from the issuer to maintain a certain liquidity. Trading profits (and/or losses) are usually carried by the issuer (i.e. the market maker is insulated from market risk).

Market Making in TradFi overall is a heavily regulated and transparent business; regulators surveil MMs to ensure they comply with their obligations. Regulators (or exchanges) can impose both positive and negative obligations on market makers, requiring them to provide liquidity to the market or preventing them from executing a trade if a retail order could execute instead of it, for example. For example, EUREX (a European derivatives exchange) states here the specifics of Regulatory Market-Making, according to MiFID II, and Commercial Liquidity Provisioning on its platform. In practice, MMs sign a contract with exchanges, and the list and details of contractual MMs are public for everyone to see. The idea is that an investor looking for liquidity may directly contact a MM.

Market Making strategies, risks & examples

Here is an overview of the most common market making strategies in TradFi:

Delta Neutral Market Making: A market maker seeks to self-hedge against the inventory risk and wants to offload it in another trading venue. For that, a MM would place limit orders on an exchange with low liquidity, and when those are filled, immediately send a market order (on the opposite side) to an exchange with higher liquidity.

High-frequency “at touch” Market Making: A common strategy for MMs is submitting limit buy/sell orders at the best bid/ask prices. The MMs bid/ask order spread is then equal to that of the limit order book (LOB). Sometimes, MMs will submit orders at prices marginally higher than the bid and lower than the ask to gain order execution priority. However, this is only possible when spreads are not already very tight. Alternatively, a market maker could place their orders further into the LOB queue (lower bid and higher ask). This strategy produces higher margins but also a lower order execution rate.

Last Price: In this case, MMs will reference the last price a security traded at when placing their bid/ask quotes, submitting bid/ask orders one or two ticks away in either direction. This strategy provides a higher return than the “at touch”; however, this comes at the expense of higher end-of-day inventory of the given security.

Grid Market Making: In this case, a market maker places limit orders throughout the book, of increasing size, around a moving average of the price, and then leaves them there. The idea is that the price will ‘walk through’ the orders throughout the day, earning the spreads between buys and sells.

These strategies work well when prices are relatively stable but may lose money heavily during sustained momentum or volatility periods. When prices keep going up, the MM will find it extremely difficult to execute bid orders, accumulating an increasingly significant losing-money short position, and the same applies in the opposite direction. MMs should pay close attention to market volatility and order book imbalances to avoid being trapped in such situations.

According to studies published in 2014 and 2021, market makers are likely to reduce their market participation in periods of significant volatility. MMs often farther into the LOB in such situations to avoid being caught out by significant and abrupt changes in the market, reducing liquidity and potentially making markets even choppier. In addition to reduced trading volumes in periods of volatility, MMs will adjust their quoting price based on movements in the order book, monitoring the LOB for any order imbalances. For example, MMs will adjust their ask/bid quotes if the volume difference between bid and ask quotes grows, expecting an uptrend in price movements.

It is also interesting to note that when MMs operate under a contract with an exchange, they will often benefit from specific technical provisions: typically, the exchange will implement a “market maker protection” which essentially cancels all orders (at once) from a MM when violent price moves occur. There are also different modalities for order management (for example, a “bulk order” functionality, whereas regular investors can only send single orders, one at a time). Those features act as an incentive for MMs to stay in the market even when volatility rises (i.e. when they are most needed) by offering specific risk management tools.

All else equal, strategies accounting for order book imbalances increase returns and end-of-day inventory. Those adjusting the bid/ask quote for volatility will also increase returns while decreasing inventory. These two strategies are hence often combined to achieve optimal performance.

One of the most significant risks of market making is the inventory risk. MMs have to store a particular amount of assets to fill a buy/sell order, and the inventory risk manifests itself every time markets start forming a trend (upwards or downwards) for a sustainable period. The inventory risk in a scenario of decreasing prices results in the risk of having more of an asset at the wrong time, with difficulties to find buyers to unwind it. This risk is vastly larger in crypto markets, where prices are more volatile.

To illustrate the above, let us give a quick example of how a basic market-making trade takes place, a MM active on a stock X shows a bid and ask price with a quote of $10.00 – 10.05 (not necessarily the same bid and ask volumes). This means that the MM is willing to buy X stocks for $10.00 and sell them at $10.05, earning a spread of 5 cents per share (in the absence of market movement, this is indeed a maximum gain). If everything goes well, the MM could buy and sell 10,000 shares at these quotes, earning $500 from this trade.

If, on the contrary, a large sell order takes place, the MM could find itself long Y shares with the best ask down to $99.95, for example. The MM is faced with the choice to hold its position if it believes prices will reverse higher, post an order to sell at $99.95, or even choose to simply trade out of the position by selling to the prevailing highest-priced buy order, locking in a trading loss.

Crypto Market Making

The market making business in the crypto space has little to do with its older, more established counterpart in TradFi. After 14 years, crypto markets are still in a “far west” state. It is not an exaggeration to say that exchanges are far from mature, from both a technical and regulatory standpoint: liquidity is low (to very low), highly concentrated on a few instruments, slippage risks are high, manipulation is frequent, and there are clear probabilities of flash crashes when large orders appear.

Market Making agreements in crypto are also different from TradFi in many aspects, mainly:

- High engagement fees: Market makers with an established name may require payments as high as $100,000 for setup fees, $20,000 monthly fees, and a $1 million BTC and ETH loan.

- Asymmetry in pay structure: The use of options (see below) creates a situation where MMs have an incentive to manipulate the price of the token. This is absolutely illegal in TradFi.

- Imbalanced deals: Token issuers had historically little negotiation room with MMs due to the uncertainty around traded volumes after listing, leading to deals mainly favoring MMs. It’s a chicken-and-egg problem: no MM means little liquidity and little liquidity means little negotiating power vis-à-vis MMs demands.

- Little to no measurement or performance: token issuers are tech-savvy but often have insufficient financial knowledge to assess actual MMs impact on liquidity. In contrast, TradFi exchanges produce quantitative assessments of liquidity provisions, and can end liquidity contracts for insufficient performance or poor compliance with stated KPIs.

- Bad actors: Crypto’s lack of regulation has attracted all sorts of fraudulent players that engage in deceptive activities such as wash trading, spoofing, or misuse of token loans.

The terms of the market-making agreement, also known as the Liquidity Consulting Agreement (LCA), often evolve around compensation: MMs will receive financial incentives to reward improvements in a token’s liquidity and market value. Typical components are service fees, options, or KPI-based fees:

- Service fees: They usually involve initial setup fees to the MM at the beginning of the agreement, recurring (monthly or quarterly) retainer fees, or no fees in times of raging bull markets when hyped tokens become profitable enough for MMs to trade (without any other sort of compensation).

- Call Options: They provide the MM with financial upside when the token’s price rises, incentivizing them to try and keep the price above a specific strike price. The use of options aligns the founders’ interests with the MM’s, but at the expense of a fair and efficient market because of the embedded incentive to artificially manipulate the token’s price. This was particularly common in bull markets when the frenzy for new tokens pushed MMs to negotiate options in their package. Due to MMs’ vastly superior financial expertise compared to token founders, using options in a MM deal is the perfect opportunity to leverage the information asymmetry and increase the MM’s value creation on the back of the token community. The use of call options is utterly absent from TradFi because it creates an incentive to manipulate the price and pump it up.

- Performance-based fees: These fees can be paid if certain thresholds are reached (volume, price, spread…). Such fee agreements are dangerous to implement as they can (also) encourage malpractices like wash trading.

- Token Loans: MMs cannot sell what they do not own. To show ask prices and sell tokens, they have access to a reserve of tokens. That reserve is usually provided free of charge by the token ecosystem from the token pool issued but not yet available to the public. There is naturally the risk that MMs cannot return the tokens and that risk should naturally be explicitly covered in the agreement.

Examples of such crypto market making agreements are public and can be found here or here.

Crypto markets also bring the question of CEXs vs DEXs market making. Market making on centralized exchanges is similar in principle to what professional firms do in Tradfi. Another critical concept is the difference between “maker” and “taker” orders. The former refers to orders where the buyer or the seller defines a price limit at which they are willing to buy or sell. Taker orders, by contrast, are orders that are executed immediately at the best bid or offer. Thus, maker orders add liquidity, and taker orders remove it. Crypto market makers must be meticulous when managing their inventory to not pay excessive taker fees (example of the fee structure on Coinbase).

Regarding market making on DEXs, we previously highlighted the process of price discovery in DeFi protocols, taking the example of liquidity pools in Automated Market Makers (AMMs) with a focus on Uniswap (qualitative and quantitative analysis).

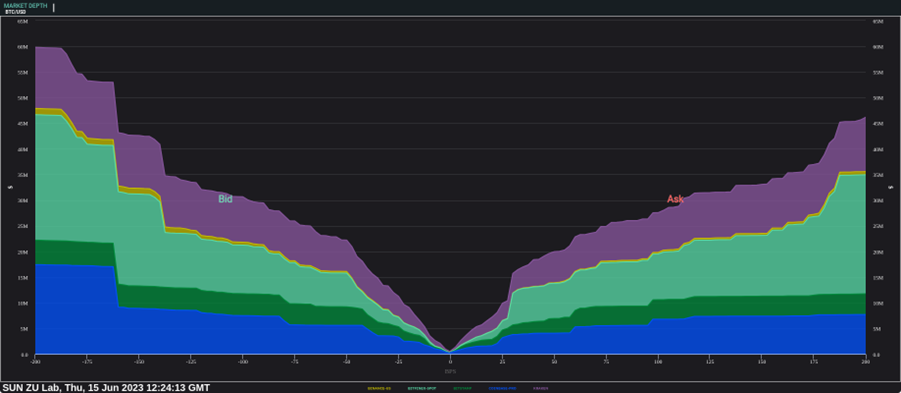

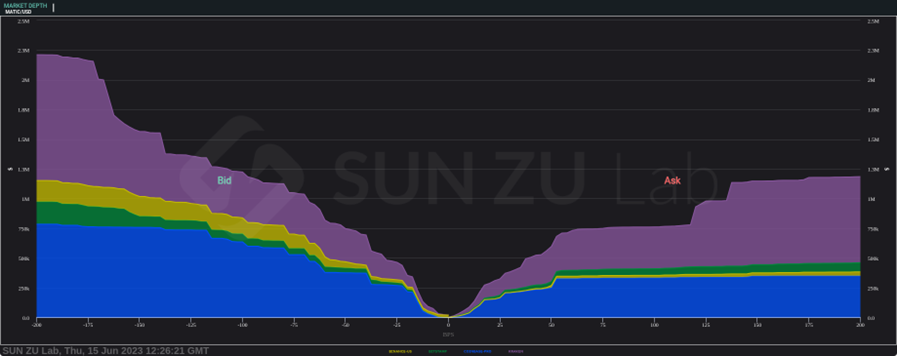

Market depth comparison between BTC/USD (~$60m/$45m bid/ask volume at 200 bps) and MATIC/USD (~$2.3m/$1.3m bid/ask volume at 200 bps), on Binance.Us, Bitstamp, Coinbase-Pro, Kraken and Bitfinex

Source: SUN ZU Lab Live Dashboard

Glossary:

- Market Maker (MM): The SEC defines a market maker as “a firm that stands ready to buy or sell a stock at public quoted prices.” A market maker (MM) is a professional trader who actively quotes two-sided markets in a particular asset, providing bids and asks for a pre-defined quantity.

- Alternative Trading Systems (ATS): also known as dark pools, are private marketplaces where investors place buy and sell orders without the venue disclosing its order book (i.e. available prices or volumes it has received from investors).

- Bid: The highest price a buyer is willing to pay to purchase a security or financial instrument. It represents the demand side of the market, and market makers provide bid prices at which they are willing to buy securities from potential sellers.

- Ask: The lowest price at which a seller is willing to sell a security or financial instrument. It represents the market’s supply side, and market makers provide ask prices at which they are willing to sell securities to potential buyers.

- Bid/Ask Spread: The difference between the highest price (bid) a market maker is willing to pay for a security or financial instrument and the lowest price (ask) at which they are willing to sell. From an investor viewpoint, the spread represents the cost of trading while it can be seen as a (maximum) profit margin for market makers.

- (Market) Liquidity: is defined as the ability to buy or sell large quantities of an asset without significant adverse price movement.

- Market Depth: The measure of the quantity of buy and sell orders at different price levels for a security or financial instrument. Market makers closely monitor the market depth to assess supply and demand dynamics, adjust their bid and ask prices accordingly.

- Order Book: A digital record of all outstanding buy and sell orders for a security or financial instrument, organized by price level. Market makers use the order book to gauge market sentiment and make pricing decisions.

- OTC (“over the counter”): refers to a type of trading where parties negotiate terms privately. It is opposed to an “organized market” where trading is governed by standardized instruments and rules, and trading is often anonymous.

- Quote: A market maker’s bid and ask prices for a security or financial instrument. Quotes are typically displayed on electronic trading platforms and reflect the market maker’s willingness to buy or sell at those prices (for a given quantity).

- Arbitrage: The practice of taking advantage of price discrepancies in different markets or instruments to make a risk-free profit. Market makers may use arbitrage strategies to capture slight price differences between trading venues or related securities.

- Regulation National Market System (Reg NMS): a set of rules passed in 2005 by the SEC that sought to refine how all listed US stocks are traded. The intention was to boost transparency by improving the displaying of quotes and access to market data and ensuring that investors get the best price on their orders.

- Regulation of Exchanges and Alternative Trading Systems (Reg ATS): became effective in 1999 and was set by the SEC to regulate trading activities on ATS.

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.

(2/2) Commentary notes on Credit Suisse’s rescue deal and recent banking turmoils

By Stéphane Reverre and Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

March 2023

Following the first article last week, where we analyzed in detail the behind-the-scenes of SVB’s fall, and after another crazy weekend with the mega-deal between UBS and Credit Suisse, one of the biggest since the GFC in 2008, we are happy to provide some further analyses on the ongoing situation.

Deal terms:

Swiss authorities sprinted over the weekend to engineer a takeover of spiraling Credit Suisse before the markets opened on Monday, a globally accomplished mission. However, nervousness was mounting on Monday in the markets following Sunday’s announcement that UBS will buy Credit Suisse for CHF 3 bn, a 95% discount to the bank’s 2010 market capitalization levels. Under the deal’s terms, Credit Suisse shareholders will receive one UBS share for every 22.48 Credit Suisse shares held, or CHF 0.76 per share (Credit Suisse closed Friday at 1.86 Swiss francs). This rescue, organized by the Swiss authorities to avoid a loss of confidence in the global banking system, was made at the cost of significant guarantees given by the Swiss government to UBS. Credit Suisse declared it intends to hand out bonuses to its staff despite the rescue deal.

Moreover, following the historic deal on Sunday, FINMA ordered that CHF 16 bn of Credit Suisse’s additional Tier one (AT1) bonds be written down to zero. AT1s were introduced as part of the post-GFC regulatory reforms to push banks to increase their capital levels. They are a form of contingent convertible security (coco) that can be converted into equity in case of trouble. This surprising decision will likely shock the market due to the hierarchy inversion between equity and bondholders. European financial regulators expressed concerns around the Swiss authorities’ decision, issuing statements on Monday to reassure holders of additional tier 1 (AT1) bonds in eurozone banks that they would not suffer the same fate as those at Credit Suisse.

How did we get here?

The 167-year-old financial institution was mismanaged for years before its collapse: conviction for cocaine-money laundering in June 2022, leaks about $8 bn in accounts of criminals, dictators, and rights abusers held by the bank in February 2022, $5.5 bn loss following Archegos default and Greensill fund collapse in March 2021, etc. Last week, the global panic surrounding the banking industry caused massive outflows from the bank (up to $10 bn per day, according to the WSJ), bringing CS to the brink of collapse.

How is the situation looking from the US side?

We learned that SVB priorly hired BlackRock’s consulting arm, Financial Markets Advisory (FMA), to analyze the potential impact of various risks on its securities portfolio. The report found that the bank lagged behind similar banks on 11 of 11 factors considered and was “substantially below” them on 10 out of 11. BlackRock’s consultants found that SVB could not generate real-time or even weekly updates about the state of its securities portfolio, but the bank didn’t take any follow-up actions. The bank was also on the Fed’s radar for over a year before its collapse; the WSJ reported that SVB was using an incorrect model as it assessed its own risks amid rising interest rates and spent much of 2022 under a supervisory review. The fair conclusion is that we’re facing a massive failure of risk management, nothing more, nothing less. Senior management failed to adjust its practices and business mix and assess the implication of the yet all-too-visible inflationary pressures with its train of rate hikes.

Regarding the upcoming FOMC meeting this week, Whatever decision the Fed takes will be heavily criticized. Suppose it decides to raise its main policy rate by 50 basis points (which would be legitimate given the level of inflation). In that case, it will be criticized for adding to the banking sector’s difficulties. This will also be the case if it raises its rate by only 25 basis points (which the market sees as the most likely scenario). Some analysts consider that it could take a break from monetary policy. This is challenging as it risks losing credibility in the fight against high inflation. Moreover, resuming a rate hike cycle quickly after stopping it is difficult. Finally, a rate cut would risk accentuating the panic and underlining that the situation on the banking front is undoubtedly worse than expected… In any case, the Fed seems bound to fail on Wednesday.

What happened as well?

- Signature board member Barney Frank claimed last week that the bank’s seizure was a political move caused by anti-crypto sentiment. At the same time, Reuters reported that the FDIC wanted Signature buyers to “give up” the bank’s crypto activities. The FDIC denied both news, revealing that Signature had suffered a $50 bn run on deposits before its closure.

- First Republic Bank, facing a crisis of confidence from investors and customers, received a $30 bn lifeline last week from a group of America’s largest banks. The bank’s stock was nonetheless down 17% ahead of the opening this morning, extending Friday’s 33% plunge.

- Gold breached $2000 an ounce while BTC is trading above $28K as the banking crisis sparks a flight to (safety) “something else” movement.

- In total, the latest data released by the Fed confirms the extent of the liquidity support given to banks. Last week alone, the Fed’s balance sheet increased by $300 billion — wiping out almost half of the Quantitative Tightening implemented since last June.

Last thoughts:

After Lehman Brothers, Bear Sterns, SVB, Credit Suisse, First Republic… senior bank management should not doubt anymore: poor risk management will kill in the blink of an eye. Crypto players, whether CeFi or DeFi, should not feel immune from this. If we had one primary piece of advice to the community, it would be K.Y.R, Know Your Risks! which is probably not so frequent in crypto.

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.

(1/2) Commentary notes on SVB’s failure Credit Suisse, implications for crypto, and where do we go from here

By Stéphane Reverre and Chadi El Adnani @SUN ZU Lab

March 2023

To be clear from the start, we do not try to undermine the gravity of what happened this weekend. The implosion of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on Friday could have quickly turned, under other circumstances, into a full-blown banking crisis in the US and worldwide. Contagion fears are far from over, as underlined by the events around Credit Suisse yesterday. We would like, however, to share some of our thoughts to reassure and clarify some points. There is already plenty of (more or less) good analyses around the bank’s failure, so we’ll dive straight into it.

1 — Summary of the events

The US banking sector had its worst week since the GFC in 2008. In a span of 2 days, Silvergate Capital collapsed, while Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) sent chills through the industry after it launched a failed effort to raise more than $2 billion in capital to bolster its capital base. SVB worked with nearly half of US VC-backed tech companies, and VC funds responded to this news by advising portfolio companies to withdraw capital. The media reported that Founder’s Fund and a16z advised portfolio companies to take these actions. SVB responded by informing select customers that it has ~$180B of available liquidity and top-tier capital ratios relative to its peers. Later the same week, US regulators closed SVB before moving to close Signature Bank as well, the last of the three crypto-friendly banks in the US. Now, one cannot help but wonder: would such a dramatic collapse have taken place if VCs had not advised their portfolio companies to withdraw their money? Intrinsically it was in their best interest to get their money out as quickly as possible, ironically though it was probably also in their best interest not to.

From the European side, stock markets fell sharply Wednesday, with banking stocks deep in negative territory following more bad news from Credit Suisse. The bank fell 24% amid growing concerns about a run after its biggest backer, Saudi National Bank, said it would not provide any further financial support.

2 — This was a very usual bank run on a very unusual bank

While Signature Bank faced a criminal probe ahead of its collapse, according to Bloomberg, Silvergate and SVB suffered from a lack of client diversification (crypto focus for the former and VC-backed tech for the latter). The events are also causing new investor concerns about some of the US and EU’s largest financial institutions. This is linked to two main factors, rising interest rates and the inversion of the yield curve, which recently dipped below 100 bps for the first time since 1981 for the 10Y-2Y yields. The inversion significantly affects banks as they usually invest their short-term client deposits into long-term bonds. As the yield curve inverts, they have to pay more on deposits than they earn on their investments, while higher rates lower the value of their existing bonds. In this context, SVB was forced to sell all its available-for-sale bonds at a $1.8 billion loss as its startup clients withdrew deposits. This situation is not unique to SVB; many banks have parked depositor money in fixed-rate government bonds that have lost value due to the rapid rise in interest rates. The FDIC recently reported that US banks are sitting on $620 bn of combined unrealized losses in their securities portfolios. SVB would have been capable of staying afloat had there not been this panic movement that eventually caused the run. (…apparently, they were already in trouble at the end of 2022 when losses were much higher than 2 bln$)

Many economists have thoroughly studied the mechanics of a bank run, but at the core of it, a run is a self-fulfilling prophecy that could annihilate the most robust of banks. As soon as a critical mass of clients is persuaded that the bank is likely to suffer a run, a race to zero is triggered by everyone trying to pull their money in an attempt to get ahead of everyone else. It all comes down to the confidence factor, and SVB’s failure was not the first but one of the biggest. There have been more than 500 bank failures in the US alone since 2008.

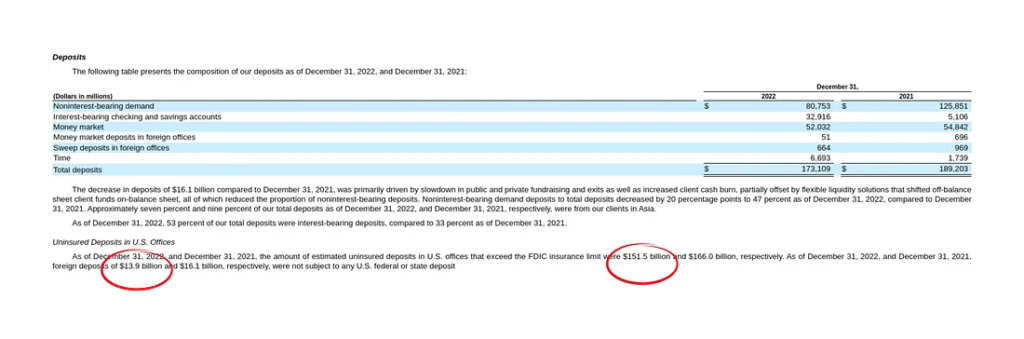

To prevent this vicious circle from getting into action, the FDIC in the US insures all accounts up to $250,000, which for a standard bank should amount to around 50% of the client base. The problem was that most of the deposits in SVB (c. 95%) were not FDIC insured as they were over the $250,000 limit. This is maybe the biggest cause of SVB’s woes: lack of client diversification outside the tech VC-backed startup base. It also needs to be clarified why so many startups were incentivized to use SVB as a bank instead of relying on a more classic and robust choice, such as JPM or BoA. Some plausible explanation would be that SVB was a primary lender to these startups, with the condition to keep their money in the bank. From this point, all it took was a bunch of prominent VCs, led by Peter Thiel’s Founders’ Fund, advising their portfolio companies to pull their money out of SVB to run the bank in less than two days.

3 — The worst is never certain — “Le pire n’est jamais certain”

Over the weekend, much speculation existed about whether the US government would intervene to save the situation. Sunday evening, the Treasury, the Fed, and the FDIC released a joint statement to inform SVB depositors that they would have access to all their money on Monday. The US startup ecosystem was saved from an “extinction-level” event, but there was little doubt that the US government would allow something this dramatic to happen.

Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen set things straight over the weekend: “Let me be clear that, during the financial crisis, there were investors and owners of systemic large banks that were bailed out . . . and the reforms that have been put in place means we are not going to do that again…”. The released joint statement later added that “Shareholders and certain unsecured debtholders will not be protected. Senior management has also been removed. Any losses to the Deposit Insurance Fund to support uninsured depositors will be recovered by a special assessment on banks, as required by law.”

Regarding the CS situation, Switzerland’s Central Bank pledged to fund the bank with liquidity “if necessary,” a first for a global bank since the GFC. In a joint statement with FINMA, they insisted that CS was sound and “meets the capital and liquidity requirements imposed on systemically important banks. Later the same day, we learned that CS would borrow around CHF 50 bn from a Swiss National Bank liquidity facility and repurchase certain OpCo senior debt securities of up to CHF 3 bn.

4 — Who lost what exactly?

Officials insisted this was NOT a bailout, as only the banks’ clients were getting their money back. President Biden later added, “That’s how capitalism works, “ referring to SVB and Signature Bank investors who lost their money.

As a reminder, the Basel III accord raised banks’ minimum total capital requirements to 8%, as a percentage of the bank’s risk-weighted assets (RWA), with a minimum Tier 1 capital ratio of 6%. Tier 1 refers to a bank’s core capital, equity, and the disclosed reserves that appear on the bank’s financial statements. Here, major US banks maintain Tier 1 capital ratios well above 10%. The Basel accords also require a minimum of 100% LCR ratios as of 2019 (The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) refers to the proportion of highly liquid assets held by banks to ensure their ability to meet short-term obligations). SVB was a category IV bank; although it was the 16th largest bank, it was never subjected to the Fed’s LCR requirements.

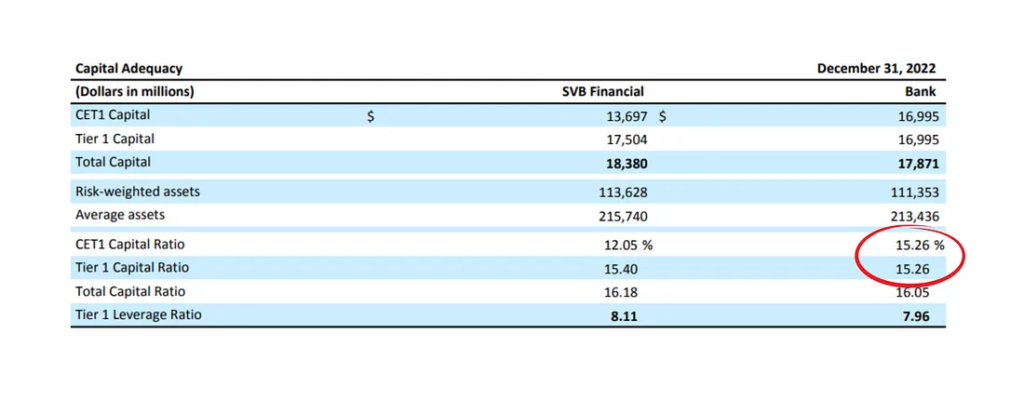

SVB’s regulatory disclosures at the end of 2022 show the following:

The bank shows $17 bn of Tier 1 Capital and $111.4 bn of Risk-Weighted Assets for a CET1 capital ratio of 15.26%.

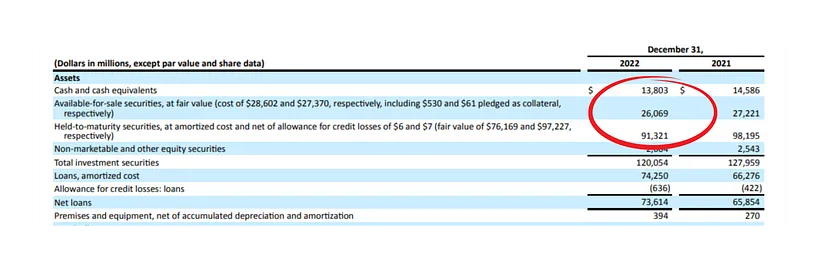

SVB Financial Group’s consolidated balance sheet is detailed below:

Was the bank solvent? Theoretically, yes! as of the end of 2022 it held:

- $14 bn in cash and cash equivalents

- $26 bn in Available-for-sale (AFS) securities

- $91 bn in Held-to-maturity (HTM) securities, invested in government-guaranteed Mortgage and Commercial Backed Securities.

- $74 bn of loans accorded to clients

These securities offer all the liquidity guarantees since they are HQLA-eligible (High-Quality Liquid Assets) and guaranteed by US state agencies. However, these securities are bonds whose value falls mathematically when rates rise, and the Fed’s rates have increased dramatically and faster than anyone had expected last year from 0.25% to 4.5%.

Moreover, the necessary disposal of part of the AFS securities to ensure the bank’s liquidity generated the aforementioned $1.8 bn in losses. The bank also disclosed in a footnote of its December 10-K Form that the HTM book had $15 bn of unrealized losses. Considering that SVB’s capital stood at $16 bn at the end of 2022, the bank only had limited capital to absorb the losses even before the run began. On paper, everything looked ok, but in reality, the rapid rise in interest rates had devastated SVB’s capital buffer (Before Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the Fed Spotted Big Problems). The fair conclusion is that we’re facing a massive failure of risk management, nothing more, nothing less. It is a failure of senior management to adjust its practices and business mix and to assess the implication of the yet all-too-visible inflationary pressures with its train of rate hikes.

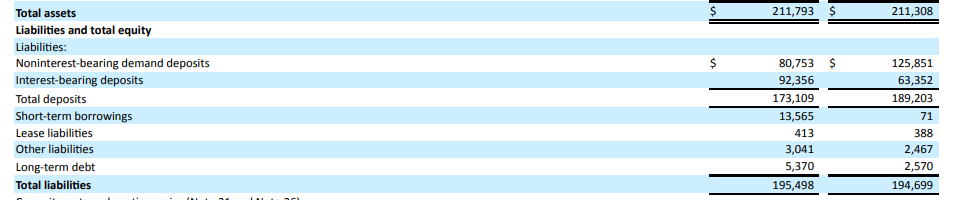

Here lies another important part of the problem. In a recent article following the events, the CFA Institute criticized HTM accounting, calling it “Hide-Til-Maturity” and advising FASB to eliminate it. They continue to precise that “Overall, SVB’s total assets at 12/31/2022 were $211.8 billion of which only approximately $40 billion (cash and available-for-sale (AFS) securities) were at fair value and immediately available to pay the $173 billion in deposit liabilities — which are all due within the next year, according to SVB’s contractual obligations table.”

Another interesting observation, rather than selling its securities on the market, SVB has liquidity lines in the form of repo agreements with bank counterparties, the FHLB, or the Fed, allowing it to collateralize its investment-grade bonds with cash. However, the management has decided to sell part of its bond portfolio quickly. We still need a convincing reason as to why they took this decision.

The deposits’ details were the following:

From the $173.1 bn in total deposits, $165.4 bn (95%) exceeded the FDIC insurance limit.

5 — What now?

Now that the FDIC controls SVB, its assets will be sold to the highest bidder. An auction on the assets already started Sunday, but there are very few banks capable of absorbing the significant quantity, and a deal has yet to be reached. SVB did not pose a systemic risk, and the US government’s quick actions over the weekend ensured the contagion didn’t spread. The events still negatively influence sentiment towards the financial sector, particularly US regional banks.

On the other hand, Credit Suisse is part of the closed club of Bulge Bracket banks imposing a global systemic-level risk. The fact that quotes for Credit Suisse’s 1yr CDS exceeded 3000 bps on Wednesday is historic and approaching a rarely-seen level that typically signals serious investor concerns.

Circle’s USDC was one of SVB’s most significant casualties over the weekend, as the firm confirmed having $3.3 bn of its $40 bn reserves in the failed bank. Over the weekend, USDC lost over 10% of its value, trading as low as $0.87 before regaining its peg on relatively joyful news Sunday evening. It is interesting to note the parallel with Tether’s USDT, which was trading at a premium for most of the weekend. In times of crisis, the market preferred Tether’s opacity to Circle’s mishandled communication. Some argued that trusting one entity with 8% of the stablecoin’s reserves was a strategic mistake.

The closure of Silvergate, SVB, and Signature, the last of the three crypto-friendly banks, creates a significant gap in the market as the industry lost 3 of its major fiat on-ramp/off-ramp partners. This will create a considerable liquidity decrease in the ecosystem, and other banks and financial intermediaries will have to step in to fill this gap.

Before last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell seemed determined to continue hiking rates until inflation returns to a long-lost 2% threshold. With the second and third largest bank failures in US history happening in less than two days, some economists predict that Powell will change his strategy to put the health of banks above all other considerations. Goldman Sachs no longer expects a rate increase at the Fed’s meeting next week, while Nomura made an even bolder prediction of a rate cut. According to Bloomberg, The ECB will forgo earlier guidance for a half-point interest-rate increase at this week’s meeting and only hike by half that amount amid concerns over the financial sector’s health. The European Central Bank should either delay or pare back this week’s planned interest-rate increase to avoid a policy error reminiscent of 2011, added former executive board member Lorenzo Bini Smaghi.

We have indeed avoided, for now, a 2008-level crisis. Still, the events will not go unnoticed, with many debates underway regarding the utility and threshold of the FDIC insurance, regulation of mid-sized banks, and the Fed’s monetary policies in times of crisis. One thing is clear; we should, at all costs, avoid creating unnecessary panic given the current fragility of the world economy.

Disclaimer

No Investment Advice

The contents of this document are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an offer or solicitation to invest in units of a fund. They do not constitute investment advice or a proposal for financial advisory services and are subject to correction and modification. They do not constitute trading advice or any advice about cryptocurrencies or digital assets. SUN ZU Lab does not recommend that any cryptocurrency should be bought, sold, or held by you. You are strongly advised to conduct due diligence and consult your financial advisor before making investment decisions.

Accuracy of Information

SUN ZU Lab will strive to ensure the accuracy of the information in this report, although it will not hold any responsibility for any missing or wrong information. SUN ZU Lab provides all information in this report and on its website.

You understand that you are using any information available here at your own risk.

Non Endorsement

The appearance of third-party advertisements and hyperlinks in this report or on SUN ZU Lab’s website does not constitute an endorsement, guarantee, warranty, or recommendation by SUN ZU Lab. You are advised to conduct your due diligence before using any third-party services.

About SUN ZU Lab

SUN ZU Lab is a leading data solutions provider based in Paris, on a mission to bring transparency to the global crypto ecosystem through independent quantitative analyses. We collect the most granular market data from major liquidity venues, analyze it, and deliver our solutions through real-time dashboards & API streams or customized reporting. SUN ZU Lab provides crypto professionals with actionable data to monitor the market and optimize investment decisions.